Talking about the economics of xeriscaping from the perspective of the home owner did cause some discussion. There were some really great comments, and I hope I start addressing some of them here.

I think that are at least two perspectives that need to be considered if we are going to understand the role of xeriscaping in water conservation. From the perspective of the home owner, using the assumptions I made, it doesn’t make financial sense. Xeriscaping an existing yard won’t pay back any time soon. I think it is important to look at it from this perspective, as it part of the reason why xeriscaping can be a really hard sell. Now, saving money isn’t the only reason to xeriscape, and I’ll try to talk about that in a future post.

For now I’ll stick with the economics, but switch to the perspective of the community. I’ll play with Kelowna numbers again, because Kelowna does a nice job of keeping records. They have a great web page, Water Use Statistics. These numbers are a good basis for setting up another toy example, this time to illustrate what xeriscaping does for the city as a whole.

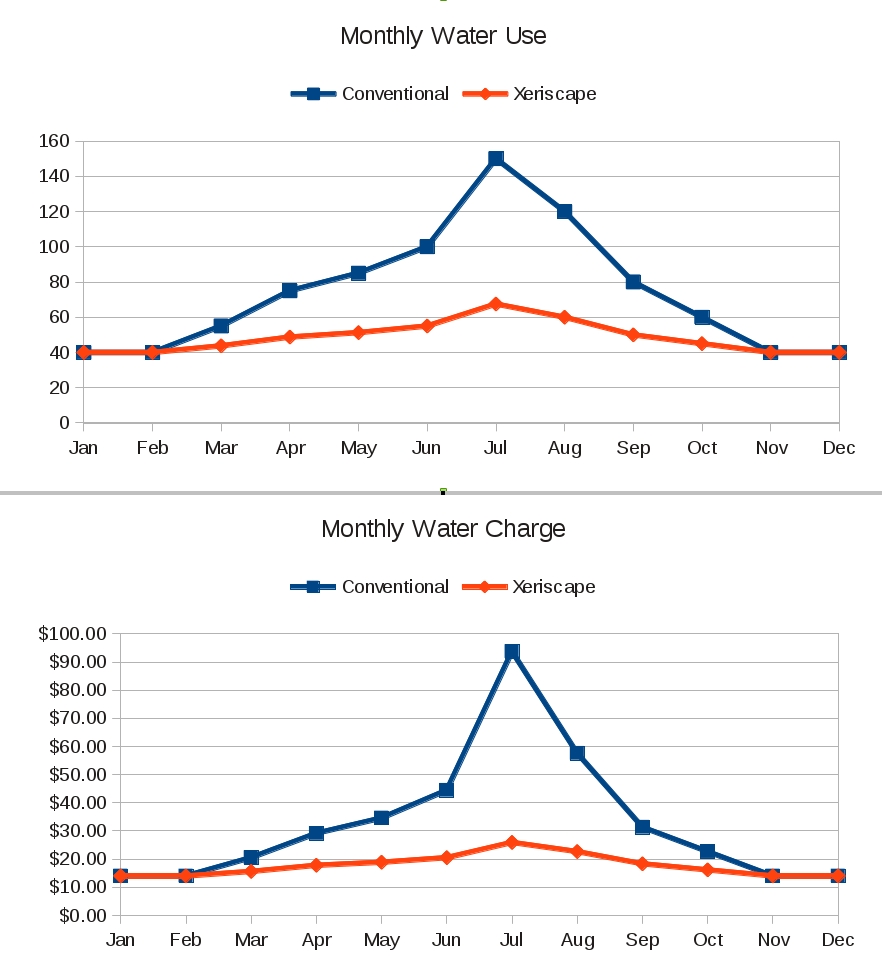

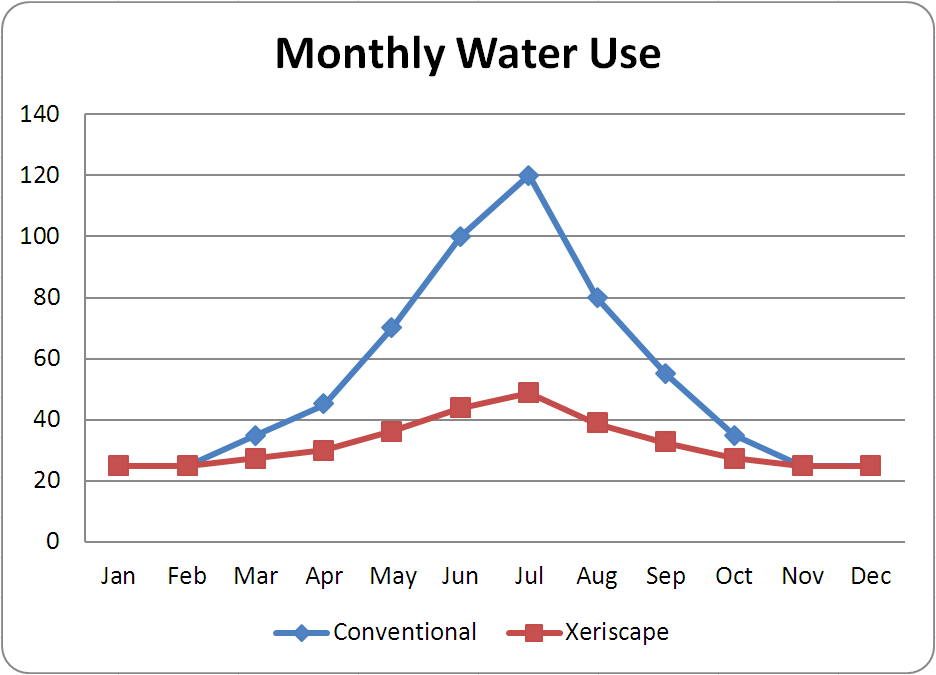

The figure below shows the annual water use pattern for an ‘average house’ that I’ve just invented.

Average single family residence, around year 2000. Conventional landscaping, 640 cubic meters per year. With xeriscaping, 385 cubic meters pear year.

I’m assuming that with xeriscaping, outdoor water use is reduced by 75%. In total, this means that the xeriscaped house uses only about 60% as much water as the conventional house.

Now taking the community perspective, a key issue is building capacity to accommodate growth. Another issue is that capacity has to be built to accommodate the peak. Expanding the total capacity to deliver water and accommodating a growing peak is expensive. Lets say that to accommodate ten years worth of population growth in Kelowna, if everyone just had conventional yards, would cost $20 million on water infrastructure upgrades.

To build that infrastructure, the city would have to borrow money. If the city can borrow money at an interest rate of 2%, then by delaying the $20 million upgrade by one year, they would save $400,000 on interest. A fair bit of change.

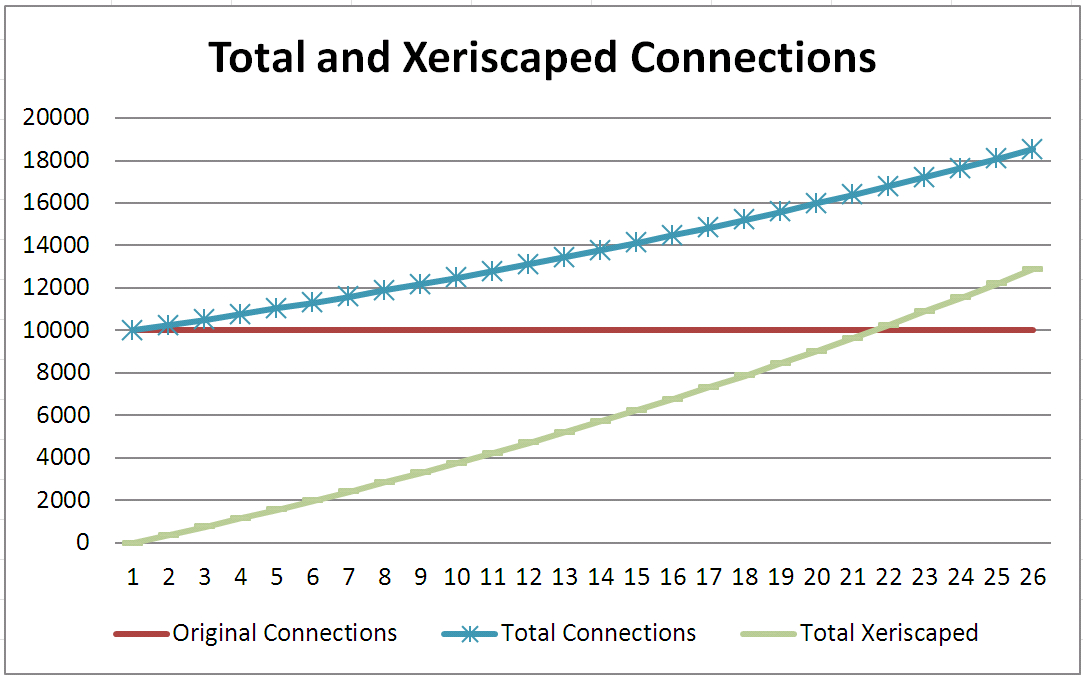

The figure above shows how many homes we would need to reduce their outdoor water use by 75% in order to accommodate the new growth. The population is take to grow at about 2.5% per year. There are 10,000 conventional homes to start. If we buy space for the new immigrants, who I assume use the xeriscape amount of water, then by converting existing yards we can delay the capacity expansion by 20 years (where the total xeriscape line hits the original connections line)!

So what does this mean for the home owner? Well, starting with the original 10,000 connections, delaying the capacity expansion by a year stops an increase in the water bill of $400,000 (assuming the city self finances this). $40 per household. That really doesn’t change the calculations in my earlier post.

However, maybe this would. The city needs to convert on average 500 homes per year. Dividing the $400,000 by 500 gives $800. The city could give $800 to each of the 500 people who xeriscape their yard. I’ve focused on xeriscaping here, but really what it boils down to is that the city has to be able to reduce the water use of existing home owners by enough to accommodate the growth. That works out to about 3% each year. So, if the city can find ways to reduce the water use of existing residents by that 3% for less than $400,000, it is a worthwhile investment.

I’ve also assumed that accommodating ten years of population growth costs $20 million. That may be in the ballpark if we are starting with 10,000 connections. However, the next capacity jump after this one will probably cost a lot more. At some point there won’t be any more water in the Okanagan that we can use, after which the only way to make space for newcomers is to reduce existing water use. When that time comes, someone who will put down half a million for a new house will hardly blink at paying an existing resident a few thousand dollars to xeriscape their yard.

So, does it make economic sense to xeriscape? On the cash alone, probably not right now. However, at some point in the future it certainly will. For now, if we are going to encourage xeriscaping, we’ve got to look for those special cases where it does make financial sense, and where it doesn’t look, for other reasons. More in a future post.

Follow

Follow