In early August I had a biopsy done on a lump in my right breast, which turned out to be cancerous. The lump was removed, together with all my breast tissue and a couple of lymph nodes, the day before I started writing this. As I start, the pathology of the removed lymph nodes has not been done, meaning I do not yet know if the cancer has been spreading beyond the breast tissue. This past month I have experienced anxiety like I have not known before. I interpreted pains, particularly in my abdominal area, as suggesting that the cancer had spread. I had an ultrasound to look for any abnormalities in my internal organs (none were found). I experienced muscle pains in my back and side that I had not experienced before. I found myself afraid that with each passing day, cancer cells were spreading along my lymphatic system from the breast lump, throughout my body.

In early August I had a biopsy done on a lump in my right breast, which turned out to be cancerous. The lump was removed, together with all my breast tissue and a couple of lymph nodes, the day before I started writing this. As I start, the pathology of the removed lymph nodes has not been done, meaning I do not yet know if the cancer has been spreading beyond the breast tissue. This past month I have experienced anxiety like I have not known before. I interpreted pains, particularly in my abdominal area, as suggesting that the cancer had spread. I had an ultrasound to look for any abnormalities in my internal organs (none were found). I experienced muscle pains in my back and side that I had not experienced before. I found myself afraid that with each passing day, cancer cells were spreading along my lymphatic system from the breast lump, throughout my body.

I tried to console myself with the facts. The five year survival prognosis for male breast cancer caught before it reaches two centimeters in size is 96% (Prognoses and Stages). As my lump was sized at 1.3 centimeters, the odds were strongly in my favour. I learned that an aggressive cancer has a doubling time of 60 days. Being an analyst, I figured out that for a 1.3 centimeter diameter tumor to double in volume, it would end up with a diameter of 1.63 centimeters. In the month between diagnosis and removal, the tumor would not have grown enough to move me to the next stage (2 to 5 centimeter tumors), where the survival probability falls to 84%. That same analysis also shows this tumor would have around 2 million cells, meaning it had to double about 21 times. Even it if is an aggressive cancer, the first cancer cell started growing there more than three years ago. My surgeon, family doctor, and other experts assured me that this cancer had been caught early, and that this meant the prognosis was good. Further, they emphasized the fact that I am relatively young and in good health, which also stands in my favour. However, my anxiety continued, and my concern continues.

So what does this have to do with water, the subject of this blog? What it highlights to me is how hard it is to think about risky and uncertain situations. For my cancer, I can do the math and quickly conclude that my odds of dying in the next five years in a traffic accident are likely not dissimilar to the odds that this tumor has spread and will kill me. I traveled to and from the hospital in a car and was nowhere near as anxious as I have been about this cancer. I think that discussions and decisions around water related issues often tap into deep seated anxieties, anxieties that make it difficult for people to work together.

So what does this have to do with water, the subject of this blog? What it highlights to me is how hard it is to think about risky and uncertain situations. For my cancer, I can do the math and quickly conclude that my odds of dying in the next five years in a traffic accident are likely not dissimilar to the odds that this tumor has spread and will kill me. I traveled to and from the hospital in a car and was nowhere near as anxious as I have been about this cancer. I think that discussions and decisions around water related issues often tap into deep seated anxieties, anxieties that make it difficult for people to work together.

Water is essential. It is essential to the riparian and aquatic habitats we want to protect. It is essential to farmers who grow our food. It is of course essential to our very survival. When people feel that something essential is threatened, anxiety takes over. This is particularly true where we don’t feel we have any control over those things that threaten our water. We worry about the safety of our tap water, and turn to bottled water. Bottled water costs hundreds to thousands of times what tap water costs, and is not itself perfectly safe either (see Center for Disease Control. However, when we buy bottled water, we feel we have a level of control. We are able to respond to our anxiety by doing something.

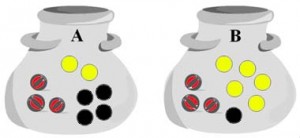

People are not very good at dealing with probabilities. Two simple experiments illustrate this again and again every time I use them myself in a classroom. The Ellsberg paradox (Wikipedia) shows that when people are faced with a risky situation – where they know the odds – or an uncertain situation – where they do not know the odds, most people try to avoid the uncertainty. The Allais paraox (Wikipedia) shows that when there is a small risk of a seriously bad outcome, people fixate on this situation and make choices to avoid it. The ironic thing about both of these paradoxes is that people change their behavior to avoid uncertainty or small probability undesirable outcomes even as the underlying situation does not change!

The Ellsberg and Allais paradoxes, and my own experience with cancer, emphasizes that rational explanations won’t get rid of peoples’ anxieties, and that people will try to take control where they can to reduce their anxieties, even when doing so doesn’t really address the source of the anxiety. If we are going to improve the way we manage water here in the Okanagan and elsewhere, we are not going to do so by using rational, fact based arguments to deal with peoples’ anxieties. Rather, we have to find ways to empower people to make choices through which they can lessen the sources of their anxiety. If we don’t provide these choices, others will certainly take advantage of these anxieties to offer them choices, even if these choices don’t genuinely help people.

The Ellsberg and Allais paradoxes, and my own experience with cancer, emphasizes that rational explanations won’t get rid of peoples’ anxieties, and that people will try to take control where they can to reduce their anxieties, even when doing so doesn’t really address the source of the anxiety. If we are going to improve the way we manage water here in the Okanagan and elsewhere, we are not going to do so by using rational, fact based arguments to deal with peoples’ anxieties. Rather, we have to find ways to empower people to make choices through which they can lessen the sources of their anxiety. If we don’t provide these choices, others will certainly take advantage of these anxieties to offer them choices, even if these choices don’t genuinely help people.

As an example, maybe if our water utilities had a small budget set aside for consumer initiated water tests, people would feel more confident in their water supply. If they knew that were they worried about their tap water, they could call their utility, and the utility would send out someone to take a sample and have it tested, they would have more confidence when their utility tells them that the water is safe. This would cost more to the utility, but it may result in their consumers using less bottled water, and thereby saving much more money. Other solutions that empower people to be part of the process of addressing their anxieties may play an important part in getting people to work together. Those of us who work in academia or are highly trained experts may need to engage people more and find out what they are worried about, rather than simply telling them to stop worrying. I certainly felt more support from those who acknowledged my anxiety about cancer than from those who simply told me to stop worrying.

Follow

Follow