The proposed changes to the Agricultural Land Commission are being spun as for the benefit of farm families (press release). It is hard to argue with someone who claims they are doing something because they want to help struggling families. However, should the issue of protecting agricultural land and the issue of helping struggling families be linked this way?

Compassion: sympathetic consciousness of others’ distress together with a desire to alleviate it (www.merriam-webster.com).

Compassion is probably one of the best human qualities. I don’t think there are many people who don’t feel for struggling families, families that are having difficulty making ends meet. I think many of these people would like to be able to do something about it. The question then is what to do.

Sustainable: of, relating to, or being a method of harvesting or using a resource so that the resource is not depleted or permanently damaged (www.merriam-webster.com).

How do we reconcile compassion with sustainability? Should we order things? For example, if a family is struggling to make ends meet, should we overlook any damage that they are doing to the environment? Should we allow them to damage the environment as a way of dealing with their struggles? If there is a poor family living in an old house with a leaking septic system next to our drinking water source, should we be compassionate and just overlook this threat to our drinking water? If that family can’t afford to pay, who should? In general, we won’t tolerate this. We will order them to repair their septic system, and if that isn’t possible, end up taking possession of the property, evicting the family, and either repairing it or demolishing it. While the whole legal process is complicated, actions like this are taken (Mission Creek, June 2013).

Should sustainability come first? Should the first condition be protecting that which is important for the environment and long term well-being of humanity and life on earth? Should compassionate actions be conditional on not compromising sustainability? Almost fifty years ago the late Kenneth Boulding argued that we are moving from a frontier economy to a spaceship economy (The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth). In a frontier economy, there is always more space and there are always more resources on the frontier. In a spaceship, everything must be conserved if we are to survive. In a spaceship, compassionate actions cannot be allowed to compromise the survival of the passengers.

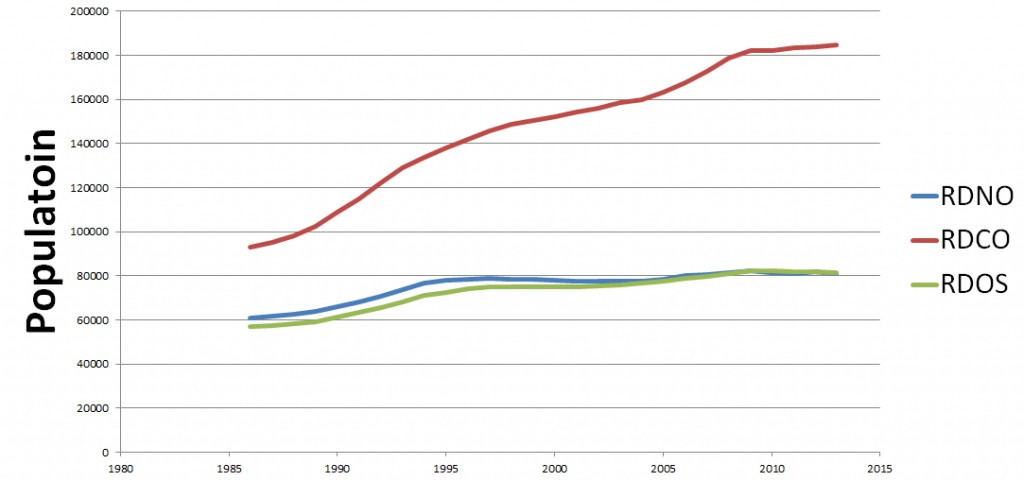

How does this relate to the Agricultural Land Reserve? Do we need to protect our agricultural land because we (or some future generation) won’t be able to survive without it? Probably not. Here in BC we only grow about half of our own food (BC’s Food Self-Reliance), and our population is growing faster than our food production. So, should we just abandon efforts to protect agricultural land here in BC? MLA Bill Bennett, champion of the proposed changes, seems to think so (the Tyee, 3 April, 2014).

Mr. Bennett is right that farm markets won’t feed our growing population and they are not a solution to the food security challenges of poor families. Farm markets tend to be expensive, selling ‘yuppy grub’. The environmental benefits of farm markets and local food is not as clear as proponents assert (US Department of Agriculture). If Mr. Bennett’s statement is correct, is his conclusion that the ALR should be weakened (or done away with)?

Community: a unified body of individuals

Indigenous: produced, growing, living, or occurring naturally in a particular region or environment

A few years ago I heard my UBC colleague Jeanette Armstrong speak, and one of the things she talked about was indigeneity. She described indigeneity about connection with place, about living in harmony with the land and environment that we inhabit. What I took away is that we can all learn to be indigenous. Learning to be indigenous means cultivating our connection with the place we live, and there is little more fundamental to connecting with the place we live than working with the land to produce the food that sustains us.

In a modern economy we cannot all be farmers, and many people don’t want to spend their time gardening. However, when agriculture takes place in our community, and when we support that agriculture in such a way that all in the community can at least share a bit of the bounty, then we are at least a little bit connected to the land. As we continue to live in the same community, we absorb the cycle of life that we are embedded in, through seeing the activities taking place on the land and through the food we consume.

So, what about helping farm families? If we want local food and we want families to be producing that food, then we should be helping families to farm. If many farm families, through no fault of their own, are struggling, then we are clearly not helping families to farm. However, I don’t see how enabling people who own agricultural land to do things other than farming is helping families to farm. It is tough when land owners see large profits that they can’t get hold of because of the ALR rules. It is even harder when a family desperately wants to stay on their land and in their community, but can’t make a living farming. I think we have to be careful to temper our compassion with wisdom. Simple solutions – families with farmland are struggling so let them use their land for other things – may be lacking in wisdom.

Follow

Follow