Recently the way agricultural land is managed in British Columbia has been in the news quite a bit. The lightening rod was the revelation that Agriculture Minister Pat Pimm and the mayor of Fort Saint John may have inappropriately tried to influence the proceedings of the Agricultural Land Commission (ALC) (B.C. Agriculture minister …). Ironically, after the ALC rejected the application to remove land near Fort Saint John from the Agricultural Land Reserve (ALR), the owner went ahead with the development anyhow, claiming that with the support of the minister, he would be successful on a re-application (Rejected by ALC, …). Anyone who has lived in or visited BC over the years will have seen the ongoing growth of our cities, and the progressive development of agricultural land. Excepting the appearance of inappropriate political interference, applications like this one routinely come before the ALC, and agricultural land continues to be developed.

Protecting agriculture and agricultural land is a ‘motherhood’ issue around the world. A simple Google search for ‘protecting agricultural land’ returns almost nine million results. One can refine this search for pretty much any country or region in the world and continue to get many results. Everywhere, people are concerned that ongoing population and economic growth is gobbling up scarce agricultural land. Most of these places are also trying something to slow this change.

In British Columbia, we created the Agricultural Land Reserve in 1973 (History of the ALR). The ALR was created to protect the capacity of the province to grow food. It was not set up to protect land that was being farmed, but to protect land that could be farmed, in case we needed it in the future. Land throughout the province was classified according to its agricultural capacity, and pretty much all high capacity land was put into the ALR. This meant that the land could not be used for purposes other than agriculture, full stop.

Well, not quite full stop. As real estate agents say, what matters is “Location, Location, Location.” Some land that is really good for agriculture is also really good for other things, like growing houses or highways. It is inevitable that as our economy and population grow, some land that once was best used for agriculture is now best used for something else. The challenge is figuring out what the best shape of our landscape is, and transitioning land from agriculture to other uses (and sometimes from other uses to agriculture) such that society as a whole is made better off.

With the ALR, the job of figuring out what land to allow out of the ALR was left to the ALC. The mission of the ALC is to “Preserve agricultural land and encourage and enable farm businesses throughout British Columbia (ALC)”. It is not the job of the ALC to figure out what the best use of the land is. It is the job of the ALC to protect agricultural land and agricultural businesses. So whose job is it to balance all the different needs of society and figure out the best use of our land base, and particularly of our scarce agricultural land? This has been the dilemma since the inception of the ALR, and no good solution has been found. Things generally stumble along under the radar until a controversy, such as this recent situation, brings the issue to the public. That launches a review and some changes to the mandate or procedures. Then things go quite again until the next controversy.

Ever since the creation of the ALR, there have been vocal critics that insist it was a stupid idea to begin with and should be abolished (BC Business). They argue that the ALR is an unfair limitation on what private land owners can do with their own land. They also argue that the pattern of land use that results from a free market is consistent with the best use of the land, and that no government actions can improve on that.

Is the free market, where land owners and developers figure out what to do with land, unfettered by controls or regulations, really consistent with what is best for society? This would be true if nothing anybody did with their own land had any impact on their neighbours. We know this isn’t true. When I start my lawn mower, whether or not I rake my leaves, how late I leave my stereo turned up, what I burn in my fire place, etc. all impact on my neighbours, and their actions impact on me. Only those who consider private property rights absolute above all else argue that neighbours just have to accept these impacts. Most people are quite happy to accept rules, such as noise bylaws and zoning rules, that limit all of our choices and thereby contain these adverse effects.

Is the free market, where land owners and developers figure out what to do with land, unfettered by controls or regulations, really consistent with what is best for society? This would be true if nothing anybody did with their own land had any impact on their neighbours. We know this isn’t true. When I start my lawn mower, whether or not I rake my leaves, how late I leave my stereo turned up, what I burn in my fire place, etc. all impact on my neighbours, and their actions impact on me. Only those who consider private property rights absolute above all else argue that neighbours just have to accept these impacts. Most people are quite happy to accept rules, such as noise bylaws and zoning rules, that limit all of our choices and thereby contain these adverse effects.

What ways does agriculture impact its neighbours? Agriculture has many positive influences that are largely lost when the land is developed for urban uses. There is of course the loss of local food production. While many of us don’t buy much locally produced food, we seem to value knowing that if we want to, we can. Some recent research highlights how much the public in BC supports the ALR, and an important reason is wanting local food production (Androkovich et al, 2008). Agricultural land also provides valuable habitats that built up areas don’t. Perhaps more importantly, it provides landscapes that we enjoy being close to. Many research studies have shown that people value living near open space, much of which is agricultural land (McConnell and Walls, 2005). Our communities become less pleasant places to live when farmland and open space is replaced by the built landscape.

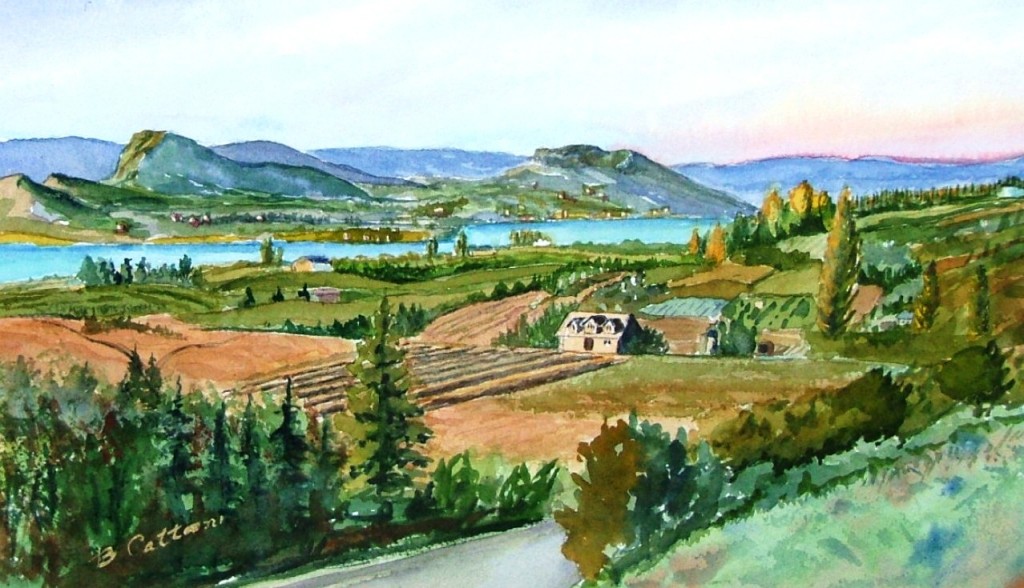

Watercolor by B.J. (Bernie) Cattani, #24 – 3333 South Main St. Penticton B.C. Canada V2A 8J8. Phone 250 493 4099

The amount someone can afford to pay for a piece of land is determined by the size of the loan they can afford to finance from what they earn using the land. If you are a landlord, that part of the rent you have left after expenses must cover the mortgage payments, with enough of a margin to deal with those times when you can’t find a tenant, or other things go wrong. Likewise, if you are a farmer, the most you can pay for that mortgage is what remains after paying all the costs of growing the crop, with a margin for those times when the crop doesn’t grow. Since nobody pays the farmer for being there ‘just in case’ people want to buy local food, nor for the deer that people like seeing on farmer’s fields, nor for the beautiful landscape that farmers take care of, farmers may not be able to make a living from their land, even though as a society we are better off if they do. Somebody who wants to develop the land will be able to pay more for it than a farmer can.

If the ALR works well, then the only thing agricultural land can be used for is agriculture, and the prices it will sell for is that which farmers can afford. However, the ALR isn’t perfect, and people who are able to get their land out of the ALR can make a lot of money by doing nothing but getting a ruling in their favour. This profit opportunity is the big problem with the ALR. Anybody who owns land in the ALR that could be sold for a lot more out of the ALR will be tempted to get it out. The fact that they may be able to get it out means they will pay more for it even when it is in the ALR than can be justified by farming income. So, farmers can’t afford to buy farmland. Speculators buy it, gambling that they will be able to get it out, and do what they need to grease the wheels and increase their odds of getting it out.

How do we fix this? Can we? Should we? The how is easy. We need to get rid of the profit potential for getting land out of the ALR. If this profit opportunity is gone, then the political pressure coming from land owners will disappear, and planners can do their work to figure out how to best manage the growth of our communities. Now, moving from this simple answer to the specific ways to do that gets harder. The city, district or province could charge a tax equal to the difference between the assess agricultural value of the land and the assessed non-agricultural value for land taken out of the ALR. The city, district or province could buy the agricultural land, change the zoning, and then sell it for development purposes. The difference would go into the revenues of the relevant authority, rather than to the land owner.

How do we fix this? Can we? Should we? The how is easy. We need to get rid of the profit potential for getting land out of the ALR. If this profit opportunity is gone, then the political pressure coming from land owners will disappear, and planners can do their work to figure out how to best manage the growth of our communities. Now, moving from this simple answer to the specific ways to do that gets harder. The city, district or province could charge a tax equal to the difference between the assess agricultural value of the land and the assessed non-agricultural value for land taken out of the ALR. The city, district or province could buy the agricultural land, change the zoning, and then sell it for development purposes. The difference would go into the revenues of the relevant authority, rather than to the land owner.

Rather than taxing away the profit potential, we could instead try to increase the value of keeping land in agriculture. The various supports for agriculture, the reduced property taxes for land that is being farmed, etc. are efforts to do that. The suggestion of an agricultural water reserve in the proposed Water Sustainability Act is a similar effort to make agriculture a bit more viable. These help, but don’t seem to do enough. They also tend to be broad policies for all of agriculture, rather than focusing on those farms that are at the urban fringe. Another approach to making farming profitable would be for the city, district or province to buy the land and then rent it out for farming uses.

Now should we? This is the really hard question. Many people dream of getting rich through real estate. Shutting this door is probably not going to be an easy sell politically, especially for people who spent a lot of money to get into this game. Likewise, anything that sounds like higher taxes isn’t going to get too far with the current political climate.

Now should we? This is the really hard question. Many people dream of getting rich through real estate. Shutting this door is probably not going to be an easy sell politically, especially for people who spent a lot of money to get into this game. Likewise, anything that sounds like higher taxes isn’t going to get too far with the current political climate.

Is it fair? Most of the value from the development that a parcel of land has is because it is in the right place. Often that right place is a consequence of growth that happened before. The owner didn’t pick up the land from somewhere else and move it to where it is valuable. She got lucky that the city grew the way it did, and won the real estate lottery. So, from this perspective, it is only fair that the community as a whole reap this benefit, as it is the very existence and growth of the community that created this value. However, we all want to have the opportunity to win the real estate lottery, so as logical as this argument may be, I’m not sure how well it will fly.

So, there are some very good reasons to manage development and protect some of the things that agriculture in particular provides to our communities. However, the current ALR creates very strong incentives to try and undermine it. Do we have the courage to try something very different, or do the majority of us want to keep open the possibility of scoring our own million dollar cheque by gambling on real estate?

- Androkovich, Robert, et al. “Land preservation in British Columbia: an empirical analysis of the factors underlying public support and willingness to pay.” Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics 40.03 (2008).

- McConnell, Virginia, and Margaret A. Walls. The value of open space: Evidence from studies of nonmarket benefits. Washington, DC, USA: Resources for the Future, 2005.

Follow

Follow