Should the city of Kelowna take over the other four water providers before any major upgrades take place? While not quite top of the news anymore, my sense is that it is far from settled. In what follows is some background, and some thoughts from the outside.

https://www.kjwc.org/

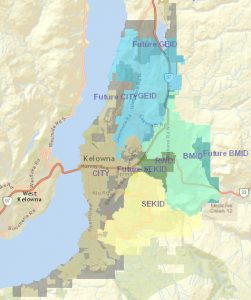

Kelowna presently has five major water providers and a collection of small ones. The five main ones are the Glenmore Ellison Improvement District (GEID), Black Mountain Irrigation District (BMID), South East Kelowna Irrigation District (SEKID), Rutland Waterworks (RWW), and the City of Kelowna. The first versions of the systems that would develop into those operated by the three irrigation districts began when land development companies recognized that they could sell parcels of land with irrigation for much more than that which was not irrigated. The systems they built took advantage of the local topography to move water from upland reservoirs to the dry lands without easy access to nearby creeks. Relying on gravity, the cost of moving water was small. The principle challenge was building enough storage and delivery capacity to meet the needs for irrigation during the summer months. After the land was subdivided and sold, the systems were often neglected by their original builders, and were eventually reorganized into a level of local government.

http://www.kelownabc.com/kelowna/

The Rutland and Kelowna systems were built to supply water to urban residents. Being distant from the lake, Rutland’s system used groundwater, while Kelowna turned to the lake. Unlike the irrigation systems, both Rutland and Kelowna must pump their water, making water delivery more costly. This at least partly explains why both of these utilities moved to metering and charging by volume. As these systems are dependent on pumping, they are vulnerable to equipment breakdown and power interruptions, and must have measures in place (generators, fuel storage, redundant pumps) to ensure that they can handle such events. Those supplied by RWW and Kelowna do tend to have fewer complaints about water quality issues, a consequence of the fact that upland reservoirs are more likely to be affected by biological activity, and the stream channels that deliver the water to the system intakes are more vulnerable to weather events that can cause turbidity.

RWW, GEID, BMID and SEKID are a level of local government, and fall under the provincial Local Government Act. Their activities are overseen by an elected board of trustees that establishes bylaws regulating the operations of the utility. For the city, by contrast, water is one of a number of services, with city politicians ultimately responsible. Unlike the other four water providers, the city’s elected officials are responsible for overseeing all the services the city provides.

The managers of all these water utilities are planning infrastructure upgrades and expansions to deal with their respective challenges. They recognize that there is scope to support each other, and cooperate through the Kelowna Joint Water Committee. In recent years, the provincial government has decided it would like to see the many, mostly small, independent water utilities around the province absorbed into other levels of local government – cities, towns, or regional districts. The five utilities mutually agreed to tighten their cooperation, and in doing so were able to arrange for continued access to funding, using the city as the conduit. This cooperation took the form of a detailed integration plan, the 2012 Kelowna Integrated Water Supply Plan, which describes the situation of each water provider, the technical needs and costs of installing physical integration between the utilities and upgrading water treatment, and explores governance reform that would reflect the emerging integrated water system.

The managers of all these water utilities are planning infrastructure upgrades and expansions to deal with their respective challenges. They recognize that there is scope to support each other, and cooperate through the Kelowna Joint Water Committee. In recent years, the provincial government has decided it would like to see the many, mostly small, independent water utilities around the province absorbed into other levels of local government – cities, towns, or regional districts. The five utilities mutually agreed to tighten their cooperation, and in doing so were able to arrange for continued access to funding, using the city as the conduit. This cooperation took the form of a detailed integration plan, the 2012 Kelowna Integrated Water Supply Plan, which describes the situation of each water provider, the technical needs and costs of installing physical integration between the utilities and upgrading water treatment, and explores governance reform that would reflect the emerging integrated water system.

Since the last local election, city council has come to question the wisdom of the integration plan, and stated that it aims to take over all the water utilities. It suggests that this would reduce costs to all those served, and bring responsibility for all water services in Kelowna under the oversight of city council. The affected parties do not all agree that this is the best solution. In reflecting on this, I am left with a number of question which I think are important to answer if the best solution is to be found. Given that I am not a technical expert, I would be happy to be corrected.

“I can’t change the laws of physics” Scotty from the original Star Trek television series.

Will amalgamation save on the cost of physical infrastructure? To paraphrase chief engineer Scotty from the original Star Trek television series, amalgamation cannot change the laws of physics. In my non-technical understanding, the physical infrastructure consists of the pipes, pumps, treatment plants and reservoirs needed to deliver water to the residences and businesses of Kelowna. Amalgamation won’t make water any lighter nor change the distances and elevations over which it has to be moved. It won’t change the quality of the water in the ground, lakes, or reservoirs. It won’t change the climate. Therefore, it won’t change the form of the most effective way to integrate the systems.

Does having five water providers prevent us from following the most effective approach to integrating the systems? Moving water is cheap when nature has lifted it for us and we can let gravity do the work. However, the water we collect above the city is more vulnerable to quality challenges in particular than that in the lake or under the ground. A simple take on the problem of choosing the best way to integrate the systems is finding that mixture of treatment plants, pipes, pumps and reservoirs which will deliver water to the residents and businesses in Kelowna reliably and of adequate quality at the lowest cost. There is a lot of evidence that the cost of delivering a liter of treated drinking water is lower for larger systems, all else equal. In Kelowna, all else is not equal. To minimize treatment costs, we could reconfigure the system so that all of Kelowna’s water is drawn from the lake, with treatment in a small number of large and low cost plants, and then distributed throughout the city. This would likely reduce our treatment costs. However, there are a lot of people in Kelowna who live quite far from the lake, and quite far above the lake. Moving to such a system would mean saving on treatment cost, but spending more on pumping costs. It would probably also require a more expensive integration of the systems than necessary to manage the water quality and quantity challenges from the  multiple sources we have. There may be some neighbourhoods around the edges where it would make sense to switch from one provider to another. However, for the bulk of Kelowna residents, my guess is that the system in place right now is probably not far from the lowest cost system, and given that it is in place and largely working, replacing it with something ‘fresh of the drawing board’ would be an expensive way of getting something that is only slightly better than what we’ve got. Therefore, it would seem that any difficulties in cooperation between the water providers are not preventing us from realizing large savings on the physical infrastructure we need to deliver water in Kelowna.

multiple sources we have. There may be some neighbourhoods around the edges where it would make sense to switch from one provider to another. However, for the bulk of Kelowna residents, my guess is that the system in place right now is probably not far from the lowest cost system, and given that it is in place and largely working, replacing it with something ‘fresh of the drawing board’ would be an expensive way of getting something that is only slightly better than what we’ve got. Therefore, it would seem that any difficulties in cooperation between the water providers are not preventing us from realizing large savings on the physical infrastructure we need to deliver water in Kelowna.

Will an integrated system have lower operations and maintenance costs? Since the water delivery infrastructure won’t be much different with or without amalgamation, neither will operations costs directly related to this infrastructure – electricity, chemicals, etc. Each utility has capital assets – vehicles, heavy equipment, tools, etc. that are used to carry out operations and maintenance activities. One could imagine reducing duplication. However, whether and how large these savings are depends on how much of this capital isn’t being fully utilized as things are presently structured. Are vehicles and equipment sitting around unused more in Kelowna than in a comparable community with one water utility? Unless there is significant waste under the current system, there won’t be much in the way of operations and maintenance savings.

Will staffing cost be reduced by amalgamation? With five water utilities, there are five offices with office staff, five billing systems, five sets of water related bylaws and regulations, etc. It is easy to imagine that administrative costs can be reduced through amalgamation. If these systems were identical, with similar sources, similar populations served, similar challenges, then there are likely benefits from amalgamation. However, the city presently draws its water primarily from Okanagan lake, has little to do with managing upland surface reservoirs, and has few agricultural customers. The irrigation districts have many agricultural customers, rely to varying degrees on upland storage, and face different water quality and quantity risks. To effectively deal with these new responsibilities, the city will have to add staff. I would expect that many of the technical staff presently working for the independent utilities would need to be retained by the city. These people have the experience and intimate knowledge of their water systems, knowledge and experience that it would cost money, time, and inevitable costly learning errors to replace. What staffing cost savings there would be would likely come from eliminating some clerical staff and closing down some offices. It isn’t immediately obvious to me that there would be much more, particularly if management of one utility requires an additional level of paid managers to oversee things.

Will there be savings from harmonizing rules and regulations? Presently, the different water utilities have different pricing policies, different development cost charges, and various different rules and penalties for violating them. Might there be some administrative simplicity from harmonizing the bylaws and regulations? Remember that amalgamation doesn’t change the laws of physics. The bylaws and regulations are unique to each system because each system is unique. Harmonization of these rules could actually create more problems if the rules being followed don’t reflect the reality of the physical system. Red tape sometimes has a purpose. If simplifying regulations means, for example, accelerating development approvals, we may end up approving development that cannot be properly serviced. Costly unplanned system upgrades may be needed, and many other water users may also see their water affected. Promising to cut red tape is politically popular. However, doing so may in the end only benefit those who the tape was holding up, and accomplish that by creating more problems for the larger community.

One challenge is that because the city does not control water services to all within its boundaries, it cannot proceed with planning activities completely in-house. Zoning changes to enable development, etc., that city council would like to approve will be contingent on the ability of the appropriate water utility to supply that new development. City staff are accountable to city council, but non-Kelowna water utility staff are not. This introduces a wild card into the conversations between council, city staff and developers, a wild card that may introduce an inconvenient risk of transparency.

One apparent simplification might be applying the same water rate across the entire city. This is apparent rather than real because the cost of delivering water is not the same across the entire city. Most people believe that everyone should be able to satisfy their basic needs for water (consumption, food preparation, sanitation, hygiene, etc.) at little or no cost. Basic fairness would suggest that people who impose extra demands on the system on account of where they choose to live or the amount of water they choose to use, all else equal, should pay more. Harmonizing prices when those prices don’t reflect the true costs that water users impose on the system encourages waste. Presently, the differences in prices across the water providers reflect their different costs. Kelowna, RWW, and now GEID, which all pump much of their water to those served have adopted volume based pricing, reflecting that pumping costs is directly related to the amount of water delivered. That BMID and SEKID do not charge residential customers by volume makes sense for these utilities, as a much smaller share of the water they supply needs to be pumped.

Will politics be less of a barrier to effective water management with an amalgamated water system? Water services in the city of Kelowna are one of a number of services that the city provides. The remaining four water providers are independent levels of local government with their own elected board of trustees, whose job it is to oversee the management of the utility. Elections need to be run, meetings held, etc., all of which has costs both in terms of time and money. There is certainly a risk that some of those involved enjoy the politics and are loath to give up their power. The common criticism of petty politicians protecting their little kingdoms. Bringing things together under one body would eliminate these costs. Some places where politics may prevent effective decisions might therefore be done away with. However, it is also possible that this more complicated politics actually produces better decisions.

To make good decisions, it is incumbent on the involved politicians, be they trustees of a water utility or city council, to become informed about the issues related to a decision. Are city council politicians, with many different responsibilities, more or less likely to find the time to fully inform themselves about the water issues of those they represent than trustees of a water utility? The impressions I have is that city council relies heavily on staff to do most of the heavy lifting, where water utility trustees are more likely to explore the issues themselves. This is reinforced by the fact that city council is elected based on a platform of issues, whereas water utility trustees are elected for water issues alone. A city counselor is unlikely to win or loose their position based exclusively on water issues. As a result, I would expect the political accountability for water issues in Kelowna to be less if the water utilities are amalgamated than as they are currently structured.

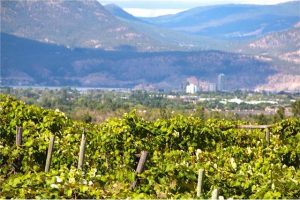

Agriculture adds a level of complexity to this situation. Irrigators use a large share of the delivered water in Kelowna, for example in the neighbourhood of three quarters of the water SEKID delivers. However, there are relatively few farmers in Kelowna, and agriculture makes up a relatively small share of the city economy. Water utility trustees, even if not farmers, are probably more likely to pay attention to farmers’ concerns than city council. Water utility trustees are not responsible for zoning decisions, sports and recreation, roads and transportation, etc. They are responsible only for overseeing their water utility, more likely to pay attention to water issues, and therefore more likely to listen to farmers.

Agriculture adds a level of complexity to this situation. Irrigators use a large share of the delivered water in Kelowna, for example in the neighbourhood of three quarters of the water SEKID delivers. However, there are relatively few farmers in Kelowna, and agriculture makes up a relatively small share of the city economy. Water utility trustees, even if not farmers, are probably more likely to pay attention to farmers’ concerns than city council. Water utility trustees are not responsible for zoning decisions, sports and recreation, roads and transportation, etc. They are responsible only for overseeing their water utility, more likely to pay attention to water issues, and therefore more likely to listen to farmers.

Are there alternatives to five or one? I do not see an obvious reason why the decision is five or one. The political reality is that independent water utilities do not have access to support from senior government that cities and regional districts do. One physical reality is that the three irrigation districts are serving users who are in the regional district but outside the boundaries of the city of Kelowna. Would it make more sense for the irrigation districts to become part of the regional district? The district is responsible for some small water systems. Is there anything that would prevent semi-independent water utilities to exist as part of the regional district? For example, could BMID continue to have a board of elected trustees and operate as an independent utility, but be legally part of the regional district? Where service requirements are clear and outside of choice – e.g. water quality standards – it is often most effective to set up an arms length entity to deliver the service. There isn’t much scope for politicians to make important choices, and their involvement can actually interfere with the effective delivery of the service. The 2012 Kelowna Integrated Water Supply Plan does include a discussion of governance of the future integrated water system. I am left with the impression that there is still much which needs to be explored before we know the best way to govern that future system. The decision may not be about five or one.

What should we do? In sum, there are probably some small cost savings that could come from amalgamation of Kelowna’s water utilities. Since amalgamation won’t change the laws of physics, most of what the five utilities presently do will still have to be done if there is only one utility. A well structured and well run amalgamated water utility could do as good a job as the present five utilities do, for what is likely a similar cost. The political aspects of water delivery in Kelowna would be simplified, but that almost surely comes with substantially reduced accountability. There is a risk that this loss of accountability may actually increase costs for the community as a whole, should important physical realities of water delivery be ignored in favor of development. The key question then is whether the potential for a small cost savings is worth the almost certain loss in political accountability and the risks that come with that.

In the short term, an integration plan exists and the utilities are only waiting for funding to move forward. Many of the steps in integrating the system will be the same, whatever the final governance looks like. It would seem to make sense to move forward with these steps when we can. I don’t see any obvious gain from putting such things off in order to adopt a governance model which doesn’t seem to offer any significant advantages.

Follow

Follow

It is pretty obvious that food security is a term that can get some people pretty excited, particularly when they see it as under threat. However, when I listen to what people are saying, I’m left with the impression that people have a range of different definitions for the term ‘food security’. As a result, we may be talking past each other, rather than with each other, which really doesn’t do much for building consensus. So, I’m going to do what academics do well, which is pick one clear definition and work through the relationship of that definition to the role of agriculture in Kelowna.

It is pretty obvious that food security is a term that can get some people pretty excited, particularly when they see it as under threat. However, when I listen to what people are saying, I’m left with the impression that people have a range of different definitions for the term ‘food security’. As a result, we may be talking past each other, rather than with each other, which really doesn’t do much for building consensus. So, I’m going to do what academics do well, which is pick one clear definition and work through the relationship of that definition to the role of agriculture in Kelowna. Within this definition, people have come to recognize four ‘pillars’: availability, access, utilization and stability. The definition does not mention local food production. If local food production is central to your definition of food security, then you won’t like this definition. If I am good with this definition and you are not, until we straighten out a common language, it will be very hard for us to get anywhere. Perhaps the way forward is to let go of the term ‘food security’, and focus on the identified pillars directly. The question then is whether or not local food production, particularly within the boundaries of the city of Kelowna, contributes to these pillars.

Within this definition, people have come to recognize four ‘pillars’: availability, access, utilization and stability. The definition does not mention local food production. If local food production is central to your definition of food security, then you won’t like this definition. If I am good with this definition and you are not, until we straighten out a common language, it will be very hard for us to get anywhere. Perhaps the way forward is to let go of the term ‘food security’, and focus on the identified pillars directly. The question then is whether or not local food production, particularly within the boundaries of the city of Kelowna, contributes to these pillars. Access. Some people talk about ‘food deserts’ (e.g.

Access. Some people talk about ‘food deserts’ (e.g.  Utilization. This is about how the food supply translates into the nutritional status of the person. Are people able to make wise choices in the preparation of what they eat and what they choose to eat, so that they are healthy. On its own, local food production has no connection to utilization. However, if local food producers help educate people who are not making the best choices for their health, then it can make a difference. Do efforts to enable the needy in our community to make healthful choices depend on food being produced in our community. They don’t. However, locally produced food can address utilization issues if it is linked to helping people make healthful choices.

Utilization. This is about how the food supply translates into the nutritional status of the person. Are people able to make wise choices in the preparation of what they eat and what they choose to eat, so that they are healthy. On its own, local food production has no connection to utilization. However, if local food producers help educate people who are not making the best choices for their health, then it can make a difference. Do efforts to enable the needy in our community to make healthful choices depend on food being produced in our community. They don’t. However, locally produced food can address utilization issues if it is linked to helping people make healthful choices. One way to think about how much we should pay is to think about the risks of our imported food supplies being interrupted or becoming suddenly much more expensive. There are lots of risks that people point out. Some fear that our global food system, which is perceived to rely on extensive monocultures, is vulnerable to pest and/or disease outbreaks that can rapidly devastate the global food supply. Some say we need to be ready in case of international conflict that interrupts supply chains. Some suggest that our modern trade treaties could collapse and trade wars ensue, making it much more difficult to import food from other countries. Some contend that our industrial food system is essentially mining the land, and that at some point it will collapse, and we need local, small scale, ecological agriculture to feed ourselves when this happens. Some argue that climate change will make some parts of the world unsuitable for growing food, and we need to protect all the productive areas we have now, to make up for this coming loss. These are some of the arguments I have heard, and I expect there are even more.

One way to think about how much we should pay is to think about the risks of our imported food supplies being interrupted or becoming suddenly much more expensive. There are lots of risks that people point out. Some fear that our global food system, which is perceived to rely on extensive monocultures, is vulnerable to pest and/or disease outbreaks that can rapidly devastate the global food supply. Some say we need to be ready in case of international conflict that interrupts supply chains. Some suggest that our modern trade treaties could collapse and trade wars ensue, making it much more difficult to import food from other countries. Some contend that our industrial food system is essentially mining the land, and that at some point it will collapse, and we need local, small scale, ecological agriculture to feed ourselves when this happens. Some argue that climate change will make some parts of the world unsuitable for growing food, and we need to protect all the productive areas we have now, to make up for this coming loss. These are some of the arguments I have heard, and I expect there are even more.

Should Kelowna’s revised agricultural plan speak to local food production as a means of addressing food security challenges in our community? Should we as a community be developing policy that takes the potential for local food production to address community food security issues and makes it a reality? The plan is being revised, and there are opportunities to contribute. If you care about these issues, you can visit the website, complete the survey, and/or attend a public event where input is sought.

Should Kelowna’s revised agricultural plan speak to local food production as a means of addressing food security challenges in our community? Should we as a community be developing policy that takes the potential for local food production to address community food security issues and makes it a reality? The plan is being revised, and there are opportunities to contribute. If you care about these issues, you can visit the website, complete the survey, and/or attend a public event where input is sought.