One of the great benefits of working with people from different countries, different cultures, or even different disciplines, is encountering new perspectives. Our minds organize the facts we collect using a framework that develops and/or is simply absorbed from our culture, our media, our education, and our disciplinary training. Our minds are very good at building a framework that works, and because it works, we seldom see any need to change it. However, like a closet organizer, there is usually a bin somewhere in the closet where we put those things that don’t quite fit. I find it rewarding when I find a new (to me) framework that does a better job than the one I’ve been using to date. The sustainable livelihoods framework, which I encountered while doing background reading for our work in Nepal, is such an example.

The basic idea of the SL framework is that people, either as individuals or collectives like households, have a set of tools that we used to sustain and enhance our livelihoods. The SL framework proposes that these tools can be organized into five different categories. These are:

- Financial capital. This is the easy one. It is just the money we can access.

- Physical capital. The built things that we use – house, car, computer, clothing …

- Human capital. Our education, experience, skills, etc. that lets us make good use of the other forms of capital.

- Natural capital. Those things that are provided by the natural world which we use.

- Social capital. The networks and relationships that support us and allow us to make better use of the other forms of capital.

The tools we have in these different categories are what create the options we have to respond to the situations we find ourselves in. A person with carpentry skills (a type of human capital) and no tools (physical capital) has less job opportunities than a person with the same skills and tools as well. If the carpenter without tools has enough money (financial capital), they can buy the tools and thereby open up more job opportunities. Someone with carpentry tools but no carpentry skills won’t have many carpentry job opportunities. They can get some training and thereby develop carpentry skills, investing in building human capital.

Many of the capital assets – tools – that the rural villagers in Nepal had access to were very specific to where they lived. The buildings, farming tools, quality of the land, the relationships with other villagers, etc. are only useful within the village. This can make people very vulnerable to local environmental change. How will villagers respond to a drought, a landslide, a pest outbreak? If we want to help, what should we do?

Many of the capital assets – tools – that the rural villagers in Nepal had access to were very specific to where they lived. The buildings, farming tools, quality of the land, the relationships with other villagers, etc. are only useful within the village. This can make people very vulnerable to local environmental change. How will villagers respond to a drought, a landslide, a pest outbreak? If we want to help, what should we do?

Thinking about the situation of the rural household and how that situation is changing helps highlight the way that the options available to the household are changing. Due to climate change, traditional ways of interacting with the environment may no longer work the way they once did. New skills and adaptive technologies can help. Economic growth and job opportunities elsewhere leads some to migrate away. This means less local labor and weaker social networks. Collective projects, such as irrigation systems, become harder to build and maintain. Should we try to sustain the village, or should we help by providing education that makes it easier for people to move away and get employment elsewhere?

I think the sustainable livelihoods framework also provides a useful way to think about Okanagan issues. Okanagan farmers have a combination of skills (human capital), equipment and facilities (physical capital) and a farm community (social capital) that they use to make the most of their land (natural capital). Unfortunately for the farmer, many of these tools have little value outside of agriculture. Over the decades a farmer works her land, she develops a relationship with that land that makes her a better manager of that land than anyone else. She has made a large investment of time and attention to build this relationship, and it serves her well in how productive her farm is. She has relied on others in the farm community to help her develop these skills and she in turn has helped younger farmers in the same way. Take her away from the farm, and these skills have little value. Take her out of the farm community, and that continuity of information flow between the generations is diminished. Farmers have a tremendous investment in their relationship with their land and in their community, an investment that they know is worth a lot less outside of agriculture.

I think the sustainable livelihoods framework also provides a useful way to think about Okanagan issues. Okanagan farmers have a combination of skills (human capital), equipment and facilities (physical capital) and a farm community (social capital) that they use to make the most of their land (natural capital). Unfortunately for the farmer, many of these tools have little value outside of agriculture. Over the decades a farmer works her land, she develops a relationship with that land that makes her a better manager of that land than anyone else. She has made a large investment of time and attention to build this relationship, and it serves her well in how productive her farm is. She has relied on others in the farm community to help her develop these skills and she in turn has helped younger farmers in the same way. Take her away from the farm, and these skills have little value. Take her out of the farm community, and that continuity of information flow between the generations is diminished. Farmers have a tremendous investment in their relationship with their land and in their community, an investment that they know is worth a lot less outside of agriculture.

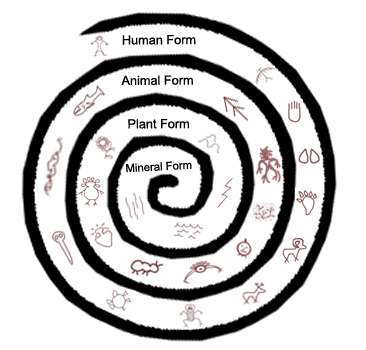

Like farmers, our Syilx friends here in the Okanagan also have a unique ‘portfolio’ of livelihood ‘capital assets.’ The Syilx culture developed over many generations of living in relationship with the land. It is through the Syilx community (social capital) that skills and knowledge (human capital) about the relationship with the land (natural capital) are transferred between the generations. This culture and the skills and knowledge do not fit easily into the framework used by most of us who have not been schooled in the ways of the Syilx people, and thus these skills and this knowledge are not much appreciated outside of the Syilx community.

Understanding that the Okanagan is occupied by different communities is valuable. If we are going to make changes to the way we manage water and other resources here in the Okanagan, we need to appreciate that these changes can affect these communities very differently. Some approaches that may seem obvious on paper or work well elsewhere might have serious negative effects on people here.

For me, the sustainable livelihoods framework makes it easier to appreciate that for people within these communities, some of the tools that they have may only be useful within their community. A new framework does not change the situation, but it may provide a new way to describe the situation and thereby to more effectively communicate the issues. A critical step in finding new ways of doing things that improve the situation for all is talking, and I hope that bringing this framework to the conversations here in the Okanagan, helps improve communications.

Follow

Follow