In the last two posts I’ve argued that xeriscaping, and by extension many things we could do to conserve water, don’t make financial sense for a household to do, even though for the community as a whole water conservation does make sense. Dr. Nancy Holmes, a colleague at UBC, is studying the ‘Okanagan Aesthetic’. I asked her to give me a few thoughts on where our landscaping choices fit.

At a poetry reading yesterday, Bill Bissett—one of Canada’s most visionary and playful poets—said something that struck me: “If only we could devote our lives to taking care of water.” How odd that sounded. We often speak of devoting our lives to taking care of many things—dogs, money, children, polar bears—but rarely water. Some of us may take care of certain creeks or river banks or ponds – we will tend lovable, proximal places in our lives, but what about “water” itself, all of it- the linking, connecting, web of water we all live in? Brendon Larsen in his book Metaphors for Environmental Sustainability (see page 103) outlines sociolinguistic research about the tendency of the English language to individuate mass nouns such as “water.” Water is not a discrete object like a car or rock, for example, but nevertheless we quite easily talk about homogenous continua like water as extractable—a glass of water, a litre of water, a drink of water. We are more likely to think of water in fragments and in separate containers and units (water in the tap, water in the bottle, water in the ocean) instead of water as a whole.

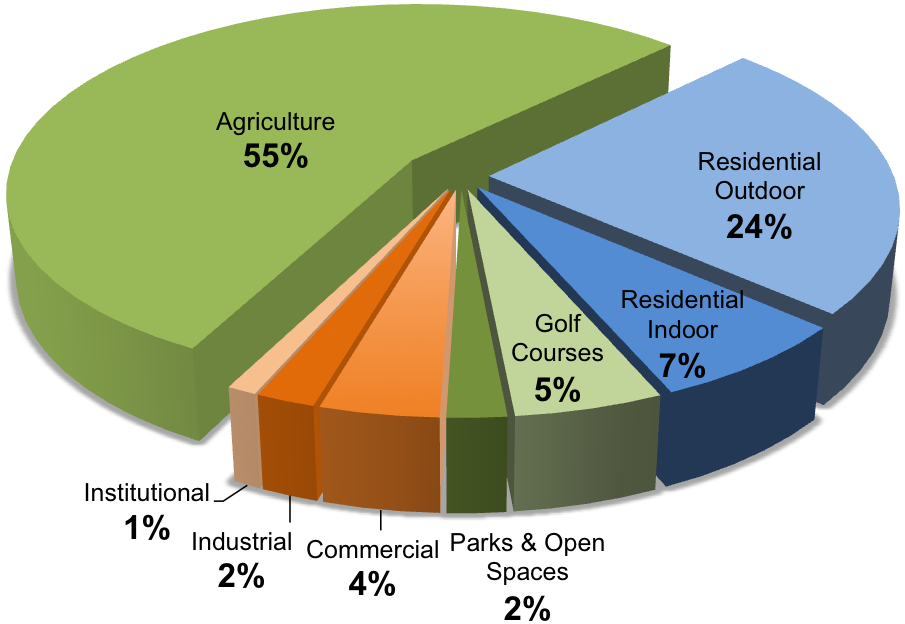

Perhaps it is because we do this so often and so easily— we English speakers— that we see green lawns and lush orchards and huge golf courses as simple, detached units in themselves not as a form of water. If we always spoke of water as the whole that it is, as immersive to us as air, would we begin to experience our own bodies as walking water, our eyes as floating light-filled bubbles, our fingers as crooked creeks? And would those green lawns, orchards, and golf courses be as startlingly wet to our eyes as a lake, green expressions of our very own body’s water spilling and running over the landscape?

I don’t think we can change how English works—though this is sometimes the role of poets, to shake English up and give us visions—but maybe we can begin to change how we see green lawns, lush orchards, and golf courses. We can shift our aesthetic values to start looking at how our water exists in this place, the arid Okanagan. Let me see my lawn as a great green pool lying loose and profligate on the landscape. Suddenly, that wet green thing burning in the heat of an Okanagan summer sun seems worrying. Green, grassy water lying up and down every suburban street is awfully exposed, drying up like great sheets in the sun. Why do we keep pouring our body’s water over them, as if they are the fevered brows of our children? Is a lawn that precious?

Now the prickly, dry hills that hoard the water in dry needles, spindly vase-like bunch grass, and crusty shells of moss seem so much more loving of water, less loose and wasteful and reckless. The dry plants of the Okanagan seem to be more tender in spirit, more careful. They are beautiful those brown, dry hills—they are austere, bent over the hot hill, collecting and nurturing their little bits of shade. They are busy devoting their lives to water.

Thanks Nancy!

I think that a lot of the ways we use water are just routine things we do. We don’t often debate the right and wrong of the length of our shower. We spend the time in the shower thinking about the day ahead, not about how much water we should be using. When we flush the toilet, we are more worried about the smell if we don’t – and hopefully doing a good job of washing our hands – than about how much water that flush will use. Changing a habit takes a lot of work. However, once it is changed, it doesn’t take much to sustain it. Changing those habits may involve a moral or financial calculation, or it may just be absorbed from what we see as common practice around us. If we look around at the natural place we inhabit, we see that water conservation is just the natural way of life here in the Okanagan. Being part of this place means conserving water.

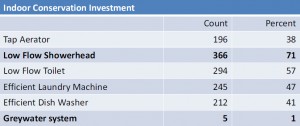

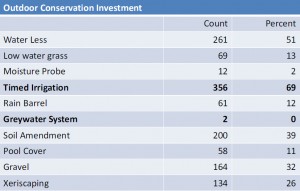

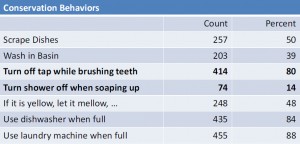

In my own research, I’ve found that many people in Kelowna do devote time and money to water conservation. You can see some of the results as part of a presentation I gave recently (Canadian Water Resources Association presentation). The tables that follow summarize water conservation choices in Kelowna among the people I surveyed:

|

|

|

I turn my shower off when I soap up, turn the tap off when I am brushing my teeth and shaving, installed dual flush toilets in my house when I recently renovated, and paid a tidy sum for two high efficiency front load washing machines. I’ve also been trying to cost effectively naturalize my yard. I’ve done these things even though my water provider does not charge me based on volume. Am I so financially naive as to make mistakes like this?

For me, when I think about it, I think water conservation is the right thing to do. There are good moral arguments. It contributes to the common good. It also brings me in closer touch with this wonderful natural space I live in. So, xeriscaping may not make a lot of financial sense, but how I choose to live my life is about a lot more than just padding my bank account. If you’ve got a yard, how are you going to landscape it?

Follow

Follow