DEADLINE EXTENDED:

Critical Education

Call for Manuscripts: Contemporary Educator Movements: Transforming Unions, Schools, and Society in North America

Special Series Editors:

Lauren Ware Stark, University of Virginia

Rhiannon Maton, State University of New York College at Cortland

Erin Dyke, Oklahoma State University

Call for Manuscripts:

Throughout the past two years, educators have led the most significant U.S. labor uprisings in over a quarter century, organizing alongside parents and community members for such common good demands as affordable health care, equitable school funding, and green space on school campuses (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2019a; Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2019b). These uprisings can be seen as evidence of the growth of a new form of unionism, alternately called social justice or social movement unionism (Fletcher & Gapasin, 2008; Peterson, 1999; Rottmann, 2013; Weiner, 2012). They can also be understood as evidence of contemporary educator movements: collective struggles that have developed throughout the past decade with the goal of transforming educators’ unions, schools, and broader society (Stark, 2019; Stern, Brown, & Hussain, 2016).

These struggles share much in common with other contemporary “movements of movements” (Sen, 2017) in that they develop in networks, utilize new technologies alongside traditional organizing tools, integrate diverse groups and demands, and often organize through horizontal, democratic processes (Juris, 2008; Wolfson, Treré, Gerbaudo, & Funke, 2017). They have been led by rank-and-file educators, who in many cases have organized in solidarity with parents and community members. While some recent scholarship on contemporary educator movements has conceptualized these movements as a unified class struggle (Blanc, 2019), other scholarship has emphasized heterogeneity, intersectionality, knowledge production, learning, and tensions within these movements (Maton, 2018; Stark, 2019).

This Critical Education special series builds on the latter tradition to offer “movement-relevant” scholarship written from within contemporary educator movements (Bevington & Dixon, 2005). Our aim for the series is to offer resources for contemporary educator movement organizers and scholars to:

- understand the links between contemporary educator labor organizing and earlier struggles,

- study tensions within this organizing,

- explore how educator unionists are learning from each other’s work,

- highlight urban and statewide education labor struggles in the U.S., as well as major struggles in Canada and Mexico, and

- connect local education labor struggles to broader power structures.

Types of Submissions:

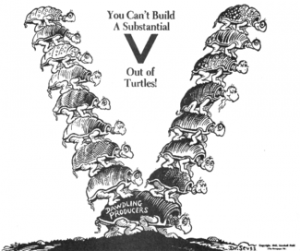

Specifically, we seek to include interviews with organizers, movement art, and empirical studies that engage critical and engaged qualitative methodologies (for example, autoethnographic, ethnographic, oral history, and/or participatory methodologies). We especially encourage submissions with and/or from rank-and-file education organizers.

- Empirical research (4,000-8,000 words)

- Interviews or dialogues with organizers (2,000-4,000 words)

- Creative writing, including poems or short prose essays (<2,000 words; maximum three poems or one essay)

- Art, including images of banner art and photographs (minimum 300dpi for images in .jpeg file format)

Examples of Possible Topics:

- The significance of caucuses and/or labor-community organizing within a specific local context,

- Challenges and possibilities for radical democratic or horizontal decision-making in contemporary educator movements,

- Possibilities and challenges in transforming teacher unions to more radical entities,

- Political education with and for rank-and-file educators,

- Rank-and-file educator organizing to engage issues of race, indigeneity, language, and culture in education,

- Issues of gender and/or sexuality in contemporary educator movements,

- In-depth studies of rank-and-file educator-led campaigns and organizing experiences,

- Tensions and possibilities between contemporary educator movements and specific North American social movements (i.e., climate justice movements, movements for decolonization, queer and trans liberation movements, prison abolition movements),

- Critical whiteness studies and education labor organizing/movements,

- Among others.

Timeline:

- April 1, 2020 – Manuscript submissions due. (Note: Manuscripts will undergo a double blind peer review process. Invitation to submit a manuscript does not ensure publication.)

- August 1, 2020 – Authors receive reviewer feedback and notification of publication decision (accept, accept with revisions, or reject for this particular series.)

- September 1, 2020 – Manuscript revisions due.

Submission Instructions:

All submissions must follow the guidelines described here. Submissions should be maximum 8,000 words and use APA format (6th edition). All work must be submitted via the Critical Education submission platform.

Use this link to submit papers: http://ices.library.ubc.ca/index.php/criticaled/about/submissions#onlineSubmissions)

References:

Bevington, D., & Dixon, C. (2005). Movement-relevant theory. Social Movement Studies, 4(3), 185-208.Bureau of Labor Statistics (2019a, February 15). Major Work Stoppages (Annual) News Release. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/wkstp_02082019.htm

Blanc, E. (2019b). Red State Revolt: The Teachers’ Strike Wave and Working-Class Politics. London & New York: Verso Books.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2019b, March 07). Eight major work stoppages in educational services in 2018. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2019/eight-major-work-stoppages-in-educational-services-in-2018.htm

Fletcher, B., & Gapasin, F. (2008). Solidarity divided: The crisis in organized labor and a new path toward social justice. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Juris, J. (2008). Networking Futures: The Movements Against Corporate Globalisation. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Maton, R. (2018.) From Neoliberalism to Structural Racism: Problem Framing in a Teacher Activist Organization. Curriculum Inquiry, 48 (3): 1–23.

Peterson, B. (1999). Survival and justice: Rethinking teacher union strategy. In B. Peterson & M. Charney (Eds.) Transforming teacher unions: Fighting for better schools and social justice (pp. 11-19). Milwaukie, WI: Rethinking Schools.

Rottmann, C. (2013, Fall). Social justice teacher activism. Our Schools / Our Selves, 23 (1), 73-81.

Sen, J. (2017). The movements of movements: Part 1. Oakland, CA: PM Press; New Delhi: Open Word.

Stark, L. (2019). “We’re trying to create a different world”: Educator organizing in social justice caucuses (Doctoral dissertation).

Stern, M., Brown, A. E. & Hussain, K. (2016). Educate. Agitate. Organize: New and Not-So-New Teacher Movements. Workplace, 26, 1-4.

Weiner, L. (2012). The future of our schools: Teachers unions and social justice. Chicago, Illinois: Haymarket Books.

Wolfson, T., Treré, E., Gerbaudo, P., & Funke, P. N. (2017). From Global Justice to Occupy and Podemos: Mapping Three Stages of Contemporary Activism. TripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique, 15(2), 390 – 542.

New issue launch Workplace: A Journal for Academic Labor #35 (2024-2025)

New issue launch Workplace: A Journal for Academic Labor #35 (2024-2025)

Follow

Follow