“The Internet gives us everything and forces us to filter it not by the workings of culture, but with our own brains. This risks creating six billion separate encyclopedias, which would prevent any common understanding whatsoever.”

– Umberto Eco

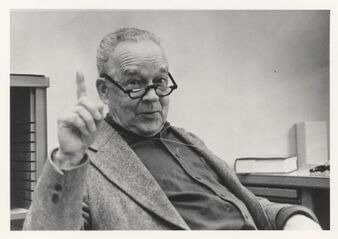

Umberto Eco was many things, an Italian medievalist, philosopher, novelist, semiotician, cultural critic, and above all, a lifelong lover of knowledge. In Umberto Eco: La biblioteca del mondo film, we see him as a scholar surrounded by books, someone whose entire being seems shaped by them. From the outside, Eco appears calm, curious, and quietly humorous, and a man who treats his library as if it were a living mind.

As a cultural critic, Eco spent his life examining how meaning is made, distorted, and forgotten in the age of mass media. Long before the rise of social networks and the internet, he warned about the danger of information overload, of a world where knowledge could be reduced to noise. The film captures that concern through the physicality of his library, where every book is resistance against digital amnesia. Unlike the virtual world, Eco’s shelves preserve the weight of memory and resist the illusion that everything should be fast, accessible, and infinite.

A central theme that emerges from the film, and that we try to explicate here, is media and memory.

The Living Library: Memory as Being & the Foundation of Knowledge

Eco describes his library as a living organism. It is more than just a collection of written archives. Rather, the library is a being that holds memory and transforms as collections are added or moved around. The film opens with Eco speaking about memory, referring to the library as a “symbol and reality of universal memory” (2:01). He categorizes memory into three forms: vegetal, organic, and mineral. The library represents vegetal memory, full of physical books that originate from trees, knowledge rooted in nature. Organic memory lives within us; it is the memory we carry in our minds. When humans say “I,” Eco explains, it is our memory speaking. Stories that are written or passed forward, imagination, fiction, all of that is memory taking the shape of culture, entertainment, conversation, etc. Finally, mineral memory is what the digital world represents, vast collections of knowledge stored as data on the silicon of computer chips. Eco emphasizes that memory is imperative to building a future. Having knowledge about what came before us and reflecting on the past, is what gives us enough insight to build a future that is worthwhile.

“We are beings living in time. Without memory, it’s impossible to build a future.” (11:08).

In Critical Terms for Media Studies, Bernard Stiegler discusses how humans have always relied on external tools to anchor memory or “exteriorize” it through language, writing, and technology. With the digital age we currently live in, and the extensive reach of information through the internet, this only gets amplified to an unfathomable magnitude, where millions of people have the ability to not only consume, but also to produce content abundantly. Stiegler elaborates on how humans have a retentional finitude. “It is because our memories are finite that we require artificial memory aids” (p.65).

These ideas align closely with Eco’s reflections in the film. He talks about how, though it is important to preserve knowledge, one needs to be selective about what they consume in order to make sense of it. An example he shares is that of a character who has the ability to remember all that he sees, and yet he is an “idiot” because all of that input is too much for a mind to conceive. Such is the state of the internet. The vastness of it is overwhelming and is, in fact, counterproductive to gaining knowledge. Eco says,

“The moment we think we have limitless knowledge, we lose it.” (26:40)

Individual organic memory, on the other hand, is selective. It acts as a limiter and rejects what is unnecessary or too complicated to perceive. This is favourable as it separates value from noise.

Knowledge, Noise, and the Loss of Meaning

We noticed that, for Eco, knowledge is not something that can be separated from the medium that holds it. He resists the idea that information should be instantly accessible, clickable, and endlessly reproduced. In the film, he says,

“Information can damage knowledge, like nowadays, with mass media and internet, because it’s too much. Too many things together produce noise, and noise is not a tool of knowledge.”(31:30)

We thought this reflects Bill Brown’s idea of the dematerialization hypothesis, the fear that digital media, by turning everything into data, threatens our “engagement with the material world” where physical objects once held meaning (p. 51). Eco resists this by grounding knowledge in material form, books that can be touched, smelled, and remembered. His library shows that thought itself has a materiality, what Brown calls “the process of thinking as having a materiality of its own” (p. 49).

It caught our attention that Eco uses the term noise to describe how the overflow of digital information harms knowledge. Bruce Clarke, in his chapter on Information, uses the very same word to describe the way excess information disrupts meaning. “Information theory translates the ratios or improbable order to probable disorder in physical systems into a distinction between signal and noise, or ‘useful’ and ‘waste’ information, in communication systems” (p. 162). He explains that information and knowledge are not the same. Information is “a virtual structure dependent upon distributed coding and decoding regimes” and can exist only when interpreted by a mind (p. 157).

Like Eco, Clarke shows that while the digital world allows infinite copies and speed, it also breeds instability and forgetfulness: “what the virtuality of information loses in place and permanence, it gains in velocity and transformativity” (p. 158). In this sense, Eco’s silence-filled library resists the entropy of digital culture. Where Clarke sees noise as both inevitable and revealing, Eco insists that too much of it actually corrupts knowledge. We think that both of them agree that without slowness, form, and material grounding, meaning dissolves into static. Noise. Meaningless.

Authenticity in the Age of Digital Reproduction

Eco’s phone is always off, and that’s exactly the point.

“It’s always out. People believe they can reach me and they cannot… I don’t want to receive messages and I don’t want to send messages!” (21:59)

He might seem quirky, but this is resistance. He’s resisting a world flooded with messages that “each of them says nothing” (22:37). It’s a world overloaded with information where meaning gets drowned in noise, a point he also makes when warning that “the risk is losing our memory on account of an overload of artificial memory.” Instead of reading and remembering, we click a button and generate a list of tens of thousands of sources we’ll never look at. “A bibliography like that is worthless,” he warns, “you can just throw it away” (26:10).

John Durham Peters, in the Mass Media chapter, critiques this same media logic. He describes mass media as a system of “one-way traffic” where the sender and receiver are separated and messages become generic and impersonal (p. 273). In contrast, Eco really values slowness, intentionality, and presence. He seems to refuse to play along with a digital, information-saturated world obsessed with sending and reacting. In that refusal, we feel he makes a statement that not replying can be its own form of meaning.

Connecting this to Walter Benjamin, we see a shared concern with how technological ease erodes authenticity. Benjamin warns that “that which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction is the aura of the work of art” (Section II/p. 221). The aura, for Benjamin, is about presence, time, and uniqueness, which are all qualities destroyed by endless replication. Eco’s fear of artificial memory speaks to this same loss. When we can generate a list of 10,000 sources in a second, the search itself becomes meaningless. Nothing is earned, and so nothing is remembered. Meaningless.

Both thinkers push back against the fantasy of instant access. The idea that more access equals more knowledge is an illusion. They urge us to resist, to slow down, and to remember that real meaning is not something you download or scroll through, it’s something you cultivate.

Reclaiming Presence & Silence in the Age of Noise

In today’s digital world, we’re constantly connected yet barely present. We scroll, click, react, and call it communication. But Eco reminds us that just because something is sent doesn’t mean it’s meaningful. All the things that he warned about, the web being an unnecessarily huge record that “causes memory to blackout,” are even more true in today’s world, where social media is an endless scroll full of options and irrelevant information, accessible at any place, right in the palm of your hands.

Eco’s refusal to be always reachable, his love for slow reading, and his quiet library all push against a world obsessed with speed and saturation. We’re taught that more information is better, but at what cost? Eco shows us the cost is lost memory, lost presence, lost meaning.

Maybe the lesson here isn’t how to keep up but how to pause. How to be intentional. How to let silence speak louder than noise. If we want to hold onto meaning in a world that drowns us in messages, maybe it’s time to stop replying and start actually listening.

Written by Kenisha Sukhwal & Maryam Abusamak

Works Cited

Benjamin, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Translated by Harry Zohn, edited by Hannah Arendt, Schocken Books, 1969.

Brown, Bill. “Materiality.” In Critical Terms for Media Studies, edited by W. J. T. Mitchell and Mark B. N. Hansen, University of Chicago Press, 2010, pp. 49–54.

Clarke, Bruce. “Information.” In Critical Terms for Media Studies, edited by W. J. T. Mitchell and Mark B. N. Hansen, University of Chicago Press, 2010, pp. 155–170.

Peters, John Durham. “Mass Media.” In Critical Terms for Media Studies, edited by W. J. T. Mitchell and Mark B. N. Hansen, University of Chicago Press, 2010, pp. 263–276.

Umberto Eco: La biblioteca del mondo. Directed by Davide Ferrario, produced by Rosamont and Rai Cinema, 2021.

Screenshot from the film (31:51).

Cover image by Kenisha Sukhwal.