Black History Month 2023: Histories in Focus

by Maria Adique, Caitlin Patterson, & Dr. Lydia Wytenbroek

As part of our Black History Month 2023 project, a team of 21 undergraduates students and myself created daily content to highlight the histories and experiences of Black nurses & to showcase Black scholars books & research. This content was then posted on Twitter (@NursingHistory) and Instagram (@ubcnursingconsortium) by students Zahra Rajan and Michele LeBlanc. Two of the students – Maria Adique & Caitlin Patterson – wrote such extensive histories as part of this project, that we wanted to also showcase their work here on the blog. You can find the link to our Black History Month 2023 project, and the full list of student participants, here: Black History Month 2023 : Historical Considerations on Nursing Education Across Canada – UBC Library Open Collections

Dr. Lydia Wytenbroek

Susie King Taylor: American Civil War Nurse

By BSN Student Maria Adique

TW: We include direct quotes from Susie King Taylor’s book in this post which deal with racism, and some viewers may find these difficult to read. Please do not advance to the images of quotes if so.

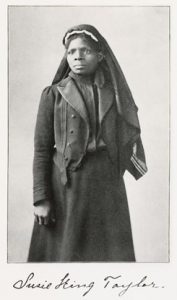

Susie King Taylor (b. 1848, d. 1912) is known for accomplishing many firsts which include being the first African American nurse to serve in the first African American regiment in the US Army during the American Civil War. She is also known to be the only African American woman to write and self-publish a memoir in 1902 detailing her experiences during the war, called the “Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33d United States Colored Troops, Late 1st S. C. Volunteers” (link below).

Introducing Susie King Taylor. Souce: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. (1970 – 1989). Susie King Taylor Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/bc284939-ebcf-beb0-e040-e00a18065af6

Taylor learned how to read and write in secret schools. She passed on her literacy to many African American children and adults. In fact, she taught the aforementioned regiment during the war. She married Sergeant Edward King in 1862. Her duties to the troops included supporting them through their suffering, helping bind wounds, getting them water, and cooking them custard which the men “enjoyed … very much” (Taylor, 1902, p.34). She was there to assist whenever needed, and was employed to be the company laundress. Taylor (1902) “did very little of it because [she] was very busy doing other things through camp” (p. 35).

After the war, she and her husband moved back to Savannah, Georgia, along with their comrades at the same time. There, she opened her own private school where she taught 20 children, and a few adults who studied at night. She taught for almost a year until a public school opened, which took her students. At the same time, Sergeant King passed away. By the end of the year 1866, she gave up teaching and prepared to welcome her child. In the spring of 1867, she opened another private school in Liberty County, Georgia. However, she did not like the country and decided to move back to the city. She left the school to Mrs. Susie Carrier.

On her return to Savannah, Georgia, she opened a private night school where she taught adults. She taught at this school until 1868, when a public night school opened and took her students once again. She placed her baby with her mother, and worked as a domestic servant to a family. However, the work was too hard on her so she ultimately moved on.

In 1872, she worked as a laundress to Mrs. Charles Green. Mrs. Green, however, would eventually go to Europe, leaving Taylor to go back to Boston. Taylor soon found herself in the service of Mr. Thomas Smith where she remained until the death of Mrs. Smith. In 1879, she met her second husband, Mr. Russell L. Taylor. She visited Louisiana in 1898 to see her very ill son. She would find that African Americans in Louisiana “have no rights here” (Taylor, 1902, p. 71). She tried but failed to purchase a berth for her son on a sleeper because he doesn’t have the strength to travel far. Taylor (1902) remarked: “It seemed very hard, when his father fought to protect the Union and our flag, and yet his boy was denied, under this same flag, a berth to carry him home to die, because he was a negro” (pp. 71-72). While in Louisiana, she encountered numerous atrocities and stories about how African Americans were treated. She went back to Boston after the passing of her son.

Near the end of her memoir, she presented her thoughts on “justice”. She wondered “if our white fellow men realize the true sense or meaning of brotherhood?” (Taylor, 1902, pg. 61). She was a staunch believer of liberty and justice that is “equal for the black as for the white”, citing that the “Southland laws are all on the side of the white” while praising Massachusetts for upholding “liberty in the full sense of the word” (Taylor, 1902, pp. 62-63). Taylor (1902) was hopeful for the future, that a time would come when her people would “attain the full standard of all other races” (p. 75).

References

National Park Service. (n.d.). Susie King Taylor. https://www.nps.gov/people/susie-king-taylor.htm

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. (1970 – 1989). Susie King Taylor Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/bc284939-ebcf-beb0-e040-e00a18065af6

Taylor, Susie King. (1902). Reminiscences of my life in camp with the 33d United States Colored Troops, late 1st S. C. volunteers (Electronic ed.). Retrieved from https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/taylorsu/taylorsu.html

Frances Davis: American Red Cross Nurse

By BSN Student Caitlin Patterson

Frances Reed Elliott Davis became the first African American nurse accepted into the American Red Cross, but her contributions extended far past this.

Frances was born in 1883 in North Carolina to Emma Elliott (the white daughter of a Methodist plantation owner/enslaver) and Darryl Elliott (a Black-Cherokee man, whose mother had been enslaved on the Elliotts’ plantation). Her parents’ union was one of controversy, as interracial relations were illegal at the time, and resulted in her father leaving when she was very young. By the time she was 5, both parents had died, and Frances passed through foster homes until settling as a teen with a minister and his wife in Raleigh, NC, where she hoped to further pursue education. Instead, she was withdrawn from school and served as the family’s nanny. Later, she found work with a supportive family, the Reeds, who helped her leave her foster family and finance her further educational pursuits.

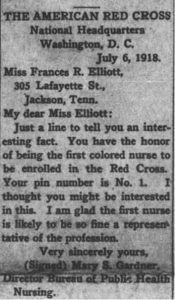

https://www.ncdcr.gov/blog/2017/08/03/world-war-i-nurse-frances-reed-elliott-davis

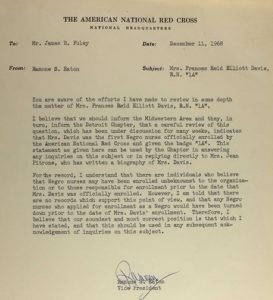

After initially working as a teacher, Frances made her way through training at the Freedman School of Nursing in Washington, DC, as nursing was her heart’s calling. Graduation examinations were stratified based on race at the time, with the exam for white nurses deemed more challenging. Frances demanded this be the test she would write, and she successfully did so, becoming the first Black person to pass the board exam in DC. She attempted to join the American Red Cross in 1916, but was rejected based on her race; she was eventually permitted entry in 1918, but was given the designation “1A” to indicate she was the first African American. The Red Cross continued to identify Black nurses with the “A” label until 1949, when the practice was finally ended.

https://www.ncdcr.gov/blog/2017/08/03/world-war-i-nurse-frances-reed-elliott-davis

https://www.ncdcr.gov/blog/2017/08/03/world-war-i-nurse-frances-reed-elliott-davis

https://www.ncdcr.gov/blog/2017/08/03/world-war-i-nurse-frances-reed-elliott-davis

When WWI began, Frances signed up for the Army Nurse Corps with a goal of tending to soldiers overseas. Red Cross nurses were permitted to transfer to the Corps during the war without issue – however, Black nurses were not granted this right. Despite her efforts, Frances was never able to serve overseas, but instead tended to soldiers in Tennessee. When the 1918 pandemic hit, Frances learned to drive so she could care for those homebound with the flu, and nursed both Black and white patients alike before contracting influenza herself and developing cardiac complications. This didn’t stop her from her work, though.

She became the director of nurses training at the John A Memorial Hospital in Tuskegee, Alabama, for the Red Cross, helped organise the first training school for Black nurses in Michigan, and managed prenatal, maternal, and child health clinics in Detroit in the subsequent years.

https://redcrosschat.org/2022/02/01/black-history-month-honoring-frances-reed-elliott-davis/

During the Great Depression, she ran a commissary at the Ford Motor plant in Inkster, a predominantly Black community outside of Detroit, to distribute now-unemployed town residents with food. She successfully petitioned Henry Ford to help provide funds and supplies for its operations. She was on the Inkster school board in the 1930s, and subsequently established a nursery in the town, the Carver School. This nursery garnered public attention, and caught the interest of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who helped raise funds to support the centre’s operations.

At the age of 69, Frances finally retired. The American Red Cross organised a ceremony in 1965 intended to honour her lifelong contributions; unfortunately, Frances passed away mere days before this was to take place. She is buried in Michigan beside her husband, William Davis.

Follow

Follow