I’m very pleased to announce that the Fourth Edition of the The Social Studies Curriculum: Purposes, Problems, and Possibilities is now in production at The State University of New York Press and will be available in 2014.

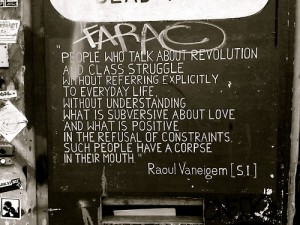

This fourth edition includes 12 new chapters on: the history of the social studies; creating spaces for democratic social studies; citizenship education; anarchist inspired transformative social studies; patriotism; ecological democracy; Native studies; inquiry teaching; Islamophobia; capitalism and class struggle; gender, sex, sexuality and youth experiences in school; and critical media literacy. Chapters carried over from the Third Edition, which was published in 2006, have been substantially revised and updated, including those: on teaching in the age of curriculum standardization and high-stakes testing; critical multicultural social studies; prejudice and racism, assessment; and teaching democracy.

As with previous editions——the first edition of The Social Studies Curriculum was published in 1997 and the Revised Edition was released in 2001——the aim of this collection of essays is to challenge readers to reconsider their assumptions and understandings of the origins, purposes, nature, and possibilities of the social studies curriculum.

A fundamental assumption of this collection is that the social studies curriculum is much more than subject matter knowledge—a collection of facts and generalizations from history and the social science disciplines to be passed on to students. The curriculum is what students experience. It is dynamic and inclusive of the interactions among students, teachers, subject matter and the social, cultural, economic and political contexts education. The true measure of success in any social studies course or program will be found in its effects on individual students’ thinking and actions as well as the communities to which students belong. Teachers are the key component in any curriculum improvement and it is our hope that this book provides social studies teachers with perspectives, insights, and knowledge that are beneficial in their continued growth as professional educators.

I am very appreciative to all the authors who wrote chapters for this and previous editions of the book, including: Jane Bernard-Powers, Margaret Smith Crocco, Abraham DeLeon, Terrie Epstein, Ronald W. Evans, Linda Farr Darling, Stephen C. Fleury, Four Arrows (aka Don T. Jacobs), Kristi Fragnoli, Rich Gibson, Neil O. Houser, David W. Hursh, Kevin Jennings, Gregg Jorgensen, Lisa Loutzenheiser, Joseph Kahne, Gloria Ladson-Billings, Christopher R. Leahey, Curry Stephenson Malott, Perry M. Marker, Sandra Mathison, Cameron McCarthy, Merry Merryfield, Jack L. Nelson, Nel Noddings, Paul Orlowski, Valerie Ooka Pang, J. Michael Peterson, Marc Pruyn, Greg Queen, Frances Rains, David Warren Saxe, Doug Selwyn, Özlem Sensoy, Binaya Subedi, Brenda Trofanenko, Kevin D. Vinson, Walter Werner, Joel Westheimer, and Michael Whelan. Each of one of these contributors are exemplary scholars and educators and their work has had a tremendous impact on my own thinking and practice as well as many other educators.

Contents

The Social Studies Curriculum: Purposes, Problems, and Possibilities

(4th Edition)

Preface

Part I: Purposes of the Social Studies Curriculum

1. Social Studies Curriculum Migration: Confronting Challenges in the 21st Century

Gregg Jorgensen, Western Illinois University

2. Social Studies Curriculum and Teaching in the Age of Standardization

E. Wayne Ross, University of British Columbia

Sandra Mathison, University of British Columbia

Kevin D. Vinson, The University of the West Indies

3. Creating Authentic Spaces for Democratic Social Studies Education

Christopher R. Leahey, North Syracuse (NY) Public Schools & SUNY Oswego

4. “Capitalism is for the Body, Religion is for the Soul”: Insurgent Social Studies for the 22nd Century

Abraham P. DeLeon, University of Texas, San Antonio

Part II: Social Issues and the Social Studies Curriculum

5. Dangerous Citizenship

E. Wayne Ross, University of British Columbia

Kevin D. Vinson, The University of the West Indies

6. Teaching Students to Think About Patriotism

Joel Westheimer, University of Ottawa

7. Ecological Democracy: An Environmental Approach to Citizenship Education

Neil O. Houser, University of Oklahoma

8. Native Studies, Praxis, and The Public Good

Four Arrows, Fielding Graduate University

9. Marxism and Critical Multicultural Social Studies Education: Redux

Curry Malott, West Chester University

Marc Pruyn, Monash University

10. Prejudice, Racism, and the Social Studies Curriculum

Jack L. Nelson, Rutgers University

Valerie Ooka Pang, San Diego State University

11. The Language of Gender, Sex, and Sexuality and Youth Experiences in Schools

Lisa Loutzenheiser, University of British Columbia

Part III: The Social Studies Curriculum in Practice

12. Making Assessment Work for Teaching and Learning

Sandra Mathison, University of British Columbia

13. Why Inquiry?

Doug Selwyn, SUNY Plattsburgh

14. Beyond Fearing the Savage: Responding to Islamophobia in the Classroom

Özlem Sensoy, Simon Fraser University

15. Class Struggle in the Classroom

Greg Queen, Fitzgerald Senior High School (Warren, MI)

16. Critical Media Literacy and Social Studies

Paul Orlowski, University of Saskatchewan

17. Teaching Democracy: What Schools Need to Do

Joseph Kahne, Mills College

Joel Westheimer, University of Ottawa

Part IV: Conclusion

18. Remaking the Social Studies Curriculum

E. Wayne Ross, University of British Columbia

Follow

Follow