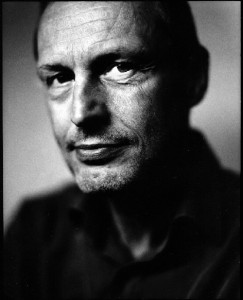

I found out this past Saturday that my long time friend and colleague Steve Fleury passed away last night in New York.

Steve was a first rate intellectual, a farmer, talented musician, a community and educational activist, storyteller and a droll comic. He studied with Jack Mallan (author of No G.O.D.s in the Classroom) at Syracuse University and was an education professor at SUNY Oswego and Le Moyne College in Syracuse where he was also a long serving department head.

I met Steve soon after I arrived in New York in 1986. I was the newbie at meetings of group of studies education profs called the NYS Social Studies Education Consortium, the group met monthly at Syracuse University, Steve’s old stomping grounds.

We hit it off and by 1989 we had guest edited a journal issue critiquing the influence of the cultural right on social studies education. By 1990, Steve and I were co-editors of Social Science Record journal and working lots of conference papers and getting to be not just colleagues but good friends.

I clocked quite a few miles on the NYS Thurway to meet up in Syracuse or his place north of the city. Sometimes we met at a little diner half-way between Albany and Syracuse to work on journal submissions. We would have breakfast, drink gallons of coffee, have serious conversations about education issues, politics, social theory, as well as music, telling stories, laughing and generally having a great time.

Steve was one of the smartest, most well-read humans I have ever known. He was a “social studies guy” but he was also scholar of philosophy, cognitive psychology and the sciences (Steve wrote a tremendous chapter for The Social Studies Curriculum book on reclaiming science for social knowledge).

He also really liked to read Lewis Lapham’s work and I too was a great admirer of him, thus we had many conversations about Lapham and the work he published in Harper’s Magazine.

Steve was a key player in the foundation of The Rouge Forum and was there in Detroit when the RF emerged from a group of social studies, literacy, and inclusive education folks and he supported the RF in very many ways, giving papers, writing articles, organizing RF meetings. We was also very involved in the political battles inside College and University Faculty Assembly – CUFA/NCSS in the 1990s-2000s.

Steve always presented as farmer first, not professor. He was always fun to be with, a self-deprecating humorist. Steve was always interested in exploring ideas. He was a great thinker, writer, and teacher. No matter the topic I always came away from our conversations with new understandings of things. We agreed on most things, but at times Steve also offered subtle, understated critiques of my perspectives or positions that pulled the rug out from under me (in a good way), opening my eyes to things had not seen before … he was engaged in pedagogical work all the time (and always loving it).

Steve was a great friend to me. He was my best man when Sandra and I got married. A few months after Colin died in 2017, he and his wife Liz came to be with us in Vancouver. Their loving and caring for us was a very important moment at a difficult and tragic time.

In the summer of 2023 we had a great holiday with Steve and Liz in Quebec City, where with their many personal connections to Quebec they gave us “the grand tour.”

Love you buddy. Thanks for everything. See you on the other side.