Vancouver faces stark contrasts between funding for K to 12 and university

Vancouver Observer

October 7, 2016

Vancouver, the city of disparities, is faced with polar opposites in its educational system.

The contrast between K-12 schools and the university in Vancouver could not be more stark: The schools sinking in debt with rapidly declining enrolments and empty seats versus the university swimming in cash and bloating quotas to force excessive enrolments beyond capacity.

With central offices just 7km or 12 minutes apart, the two operate as if in different hemispheres or eras: the schools laying off teachers and planning to close buildings versus the university given a quota for preparing about 650 teachers for a glutted market with few to no jobs on the remote horizon in the largest city of the province.

There is a gateway from grade 12 in high school to grade 13 in the university but from a finance perspective there appears an unbreachable wall between village and castle.

Pundits and researchers are nonetheless mistaken in believing that the Vancouver schools’ current $22m shortfall is disconnected from the university’s $36m real estate windfall this past year.

The schools are begging for funds from the Liberals, who, after saying no to K-12, turn around to say yes to grades 13-24 and pour money into the University of British Columbia, no questions asked.

There may be two ministries in government, Education and Advanced Education; there is but one tax-funded bank account.

At first glance, the cheques suggest parity across the Vancouver system. For 2016-17, the schools, with about 49,000 students get a base operating grant of $436m and the university, with about 42,000 students gets a base of $420m. So what’s the problem?

One is left to birth and migration rates while the other is manipulated with enrolment quotas. For each decrease of enrolment in the Vancouver schools the University ironically matches with an increase of teachers for the job market.

UBC’s Faculty of Education, which could be financially assisting the schools to meet this historic shortfall, is instead bloated with a $2.6m deficit partially to maintain a quota for a steady flood of new teachers into Vancouver.

With the building boom at UBC, in March the Faculty of Education occupied a floor and a half of the new Ponderosa Commons building, despite about two floors of unoccupied or underutilized space in its Scarfe building. Education’s share of the $57m building is $18m.

At the same time 21 Vancouver schools were scheduled for closure or demolition to meet a shortfall the government gave a $19.5m windfall to renovate UBC’s Life Sciences building.

Wheeling and dealing, the Liberal government is robbing Peter to pay Paul, demoralizing Petra to pump up Paulette.

UBC appears to be throwing money around like it grows on Endowment Land trees. With the Vancouver real estate boom, it does.

The short history of UBC at 100 years is that it was born spoiled with a sizeable estate in 1915-1916 and remains spoiled in 2016-2017.

Through the stroke of a pen in 1858, Queen Victoria created the colony of British Columbia and transformed First Nations traditional territory into Crown Land. In 1907, an amendment to the BC Land Act granted 3,000 acres (5 sq. miles) to a University Endowment.

UBC property sits precariously on unceded Musqueam territory aggressively developed by settlers into prime Vancouver real estate over the past century and most aggressively since 1988 when the UBC Real Estate Corporation (Properties Trust) was established. In 1994 UBC converted 200 acres of its campus and Endowment Lands into condo and shopping centre development.

By 2003, as University Hill Secondary school was crammed and the urban plan expanded, so flush with cash was the university that its Properties Trust offered to bankroll renovations to its National Research Council (NRC) building and charge the busted VSB a monthly lease. In 2008, the Liberals stepped in, effectively saving the university from a $37.9m renovation.

The Vancouver Schools have had to defer $700m of building maintenance costs while UBC has announced plans for an $822 million building boom on it campus, with generous commitments from the Ministry.

As in real estate goes demographics: from boom to bust, the empty seats in Vancouver schools will inevitably be empty seats in the university. Like the VSB, it won’t be long before UBC begins to schedule the closure or demolition of empty academic buildings, that is, if someone opens the doors to realize there’s no one inside.

With more and more faculty members preferring to work at home, save for staff, empty offices are making hollow buildings the norm.

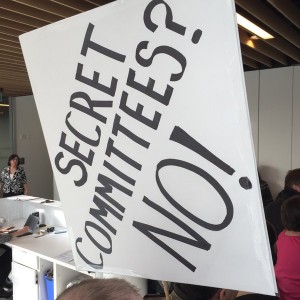

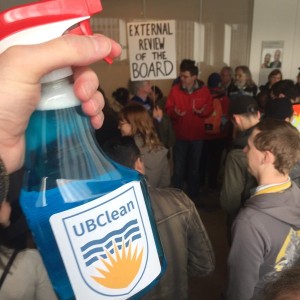

The Ministry is now threatening to fire the School Board for suspending school closure and demolition plans but when the University Board colludes to hide decisions from access and scrutiny the Ministry looks the other way.

Vancouver is now desperate to resolve the deepest school finance crisis and worst university administrative legitimacy crisis in 100 years. False distinctions between the two or the success of one at the expense of the other are at the root of the crises.

It’s the story of Vancouver: Broke and barely making it versus fixed, rich, and laughing all the way to the bank: 99% versus 1%.

Stephen Petrina and E. Wayne Ross are professors in the Department of Curriculum and Pedagogy at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

Follow

Follow