So today OLT had its monthly departmental meeting, and as part of it engaged in a World Cafe dialogue on what our “values” as a unit might be… I’ll be honest, the sounds of something like this usually brings out the McNulty in me, but I had a good time. It helped that the session was very well facilitated, that I have so much affection and respect for the people I get to work with — I found myself particularly provoked hearing what our student employees had to say.

Apparently “distance education” (or we might say technology-based distributed learning) has been part of UBC for what will soon be sixty years. Being the type of person who talks a lot more in these exercises than I probably should, I offered the assertion that “values” are a product of time and culture, and that it would be hard to imagine the distance educators of 1949 engaging in a “values visioning” exercise at all, much less coming up with the same sorts of values that we would. Most people seemed to agree – if only to shut me up, perhaps – but one person in our unit (whose experience and expertise vastly outstrips mine) strongly disagreed, suggesting that these values are more or less universal.

I think this question speaks to a fascinating thought experiment of a fairly classic epistemic problem.

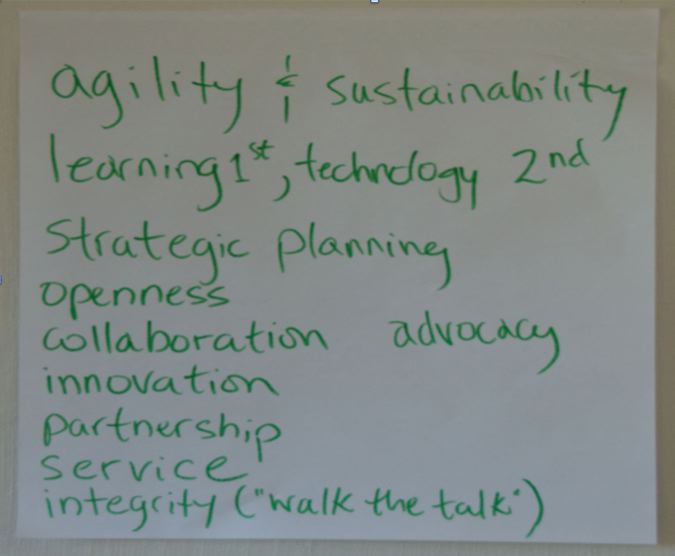

Here are some values expressed by our “strategic planning and operations” group (not the unit as a whole) a few months back:

I’m ignorant of the history of educational technology (maybe Dr. Schwier or one of his proteges can help) but I have a hard time imagining people in 1949 coming up with a list like this. Even accounting for shifts in terminology, the only potential common threads I see here are ‘collaboration’, ‘service’ and ‘integrity’ (and in all cases, I think what would be meant by those concepts would be different).

Am I being small or shallow-minded? How many of the values that (we might assume) are (mostly) shared by educational technologists today might also have guided our predecessors? “Access” comes to mind… others?

I have no relevant comment to add to this post, but had to smile at picking up your McNulty reference (I just finished end of Season 2 by getting them serially via NetFlix) and reading the WikiPedia reference that the actor playing this role is British, which made that whole scene in the mid part of season 2 more funny when McNulty was doing a really bad British accent.

Oh well.

I gotta get my comments out somehow. Good luck with all the visioning stuff.

It’s funny you should write this, because a post on the OL Daily I read yesterday came to mind. In particular, this one, wherein Downes enumerates his set of principles for public service based on Don Ledingham’s post. What I liked about what he had to say about the principles listed, a couple of which show up on your white board, is that they are merely descriptive, not normative. And with this I think he was suggesting that not everyone applies to these values, not can they necessarily be understood as the core, universal, essential principles through which public service is understood. Now I may be wrong with my reading of his post, but it actually gives me a good place to jump off. Let’s think about what edtech might have been at major research universities in 1949 (60 years ago)–at least in the US. It would be post-WW2, the emerging Cold War would be rearing it’s ugly head, the commie’s would be ever more feared, and the GI Bill would be in full effect. Consumerism on the rise, and Levitttown’s emerging for your suburban pleasure.

In fact, this is in many ways also the birth moment for the discipline of American Studies, which if I can draw a parallel, was in many ways born out of COld War research funding a kind of cultural think tanks to suggest why the US is exceptional, and why we could never be dirty commies. Out of this was born some pretty fascinating literary scholarship, I’m very much a fan of Perry Miller–although I don’t agree with him often–that reall framed an American Renaissance through a variety of 19th century writers and used it as a way to speak directly about a unique culture and mindset that was somehow essentially different from that of the Europeans and Russians etc. All by mean of suggesting unlike these countries that were allowing the emergence of communist and socialist parties (I think particularly of Italy here), the US is an many ways immune to this given it’s uniquely different national character. And along with any literary tradition comes a very staunch nationalist tradition, which was very much what the emerging filled of American Studies was premised on shaping and controlling—which might be understood as the way in which Americans understood the principles of America.

Within such a Cold War landscape of forming nationalist identities and unparalleled economic growth, the idea behind research in general was more akin to a kind of intellectual arms race wherein the scientific discoveries were closely guarded and the literary and humanities were geared more towards a propaganda-like protectionism of an exceptional national identity. And while this is somewhat of a generalization, I think the over the course of the next fifty years you you can trace a series of battles over these principles though universities. Think about the fact that colleges became the sites of so much revolutionary through and civil unrest amongst students in the 60s. Why did these institutions become the home of so many of the major uprisings of that moment (Columbia U, Kent State, etc.)? I think it may be this nationalist doctrine of superiority that was tightly woven into maintaining a status quo at universities that was in large part premised upon—and funded by—on patriarchy, racism, and the military-industrial complex.

In fact, tracing the intellectual and philosophical trends of theory over the last 60 years in many ways deals with the very minefield of some kind of universal values by which we understand any given culture at any given time. And I think that American Studies as a fild is almost unrecognizable in so many regards only 50 years later. Which questions of ethnicity, race, gender, and class at the forefront of thought. Larger critiques of nationalism and the American empire also undergird much of the writing and thinking in the academy over the last twenty years, which is so radically different from the dominant principles that drove scholars in the 50s. It is the dialogic struggle through ideas that makes principles merely descriptive as Downes suggests, what is at the heart of any principle is the cultural context through which a struggle emerges and an organization like a university finds itself situated. Universities in the 50s had a whole new breed of students thanks to the GI Bill, and the funding was quite robust. Moreoer, there wasn’t a publishing revolution on par with the Gutenberg press that universities are choosing to ignore, as we see in our moment.

Additionally, the economic situation of our time is far more similar to that of the 1930s, and it would be fascinating to trace the changing ideals of universities from the late 20s and 30s with that of the late 40s and 50s–I’m thinking of F.O. Matthieson liberal brand of American Studies here—particualrly given the economic context of these two moments. And while the university was far less elite in the 50s given the GI Bill, that fact also allows for the elliding of a perceived elitism, a necessary ingredient of any nationalist framework. In fact, the liberal leanings of Matthieson still very much championed the democratic ideals of equality, freedom, and the unbounded opportunity in the US—all values that would come under fire given in later decades give that they’re far more descriptive than normative–to use Downes’s terms–or even more abstracts than concrete realities of the culture at that moment for large parts of the population.

So, are values immutable? If you applied this logic to just about any discipline specific or cultural/historical examination—it would quickly break down. And while we try and hold up some kind of universal truths of what any institutions mission is at any given time, they are often far more descriptive than normative—for norms necessary change, and if they don’t within the academy, well then the academy itself becomes irrelevant. And isn’t that the real danger, and the struggle over principles and values, this is unique to our moment?

P.S. –Don’t ask me why I wrote an essay in your comments, I’m feeling kind nuts these days. Forgive me, and I fully recognize there is a whole lot more mis-remembering and generalization than anything useful in the above comment, but humor me anyway.

Not only are values mutable, but I can hardly imagine that in 1949 they had any “World Cafe dialogues” to elicit or articulate them.

On the changing idea of the university, a modern classic is Bill Reading’s The University in Ruins.

Hi. Devil’s Advocate here. I see many of those values expressed in the history of the Open University http://www.open.ac.uk/about/ou/p3.shtml , obviously renowned for distance education.