Written By: Julie Qiu and Wei Cui

Posted on: June 26, 2020

Peng Zhen speaking at a conference of the NPC Legal Affairs Commission

Since the COVID-19 epidemic broke out in Wuhan in January 2020, sub-national People’s Congresses (PCs) in many Chinese provinces and cities have announced policies regarding the control and prevention of the disease and economic recovery. Many of the policy documents promulgated have the same function and effect as local statutes (difang fagui), and have been pronounced as having the effect of law. But they often came with the title of “decisions” or “resolutions” (jueding). Both in name and in the procedure of adoption, this particular parliamentary instrument is to some extent distinguishable from the adoption of local statutes under the Law on Legislation. In previous decades, it was seldom used independently in providing for individual’s legal rights and obligations.

To invoke potential comparisons with non-statutory parliamentary actions in Canada and other jurisdictions, we provisionally refer to these instruments as “resolutions”. The subnational parliamentary “resolutions” on COVID-19 that were adopted in February and March 2020 are related to the increasingly frequent exercise by Chinese PCs of their resolution power regarding “major issues” (zhongda shixiang jueding quan) in the last few years. This potentially important development has not been previously noted in Western media or scholarship. We offer a brief background on the history and legal basis of the resolution power.

Article 104 of China’s Constitution grants PCs above the county level the power to “discuss and decide” major issues in all fields of work in its jurisdiction. Article 44 (4) of Organization Law for Local People’s Congresses and Local People’s Governments at All Levels (Local Organizational Law) further provides that PCs above the county level have the powers to discuss and decide major issues in “politics, economy, education, science, culture, public health, protection of the environment and natural resources, and civil and ethnic affairs in their jurisdictions”. While these may be regarded as the Constitutional and fundamental legal basis for PCs’ resolution power, they clearly say little about the extent of the power, nor how it would be exercised. Instead PCs are granted discretion to make rules themselves regarding this aspect of their competence.

The powers of PCs in China are sometimes said to be divided into four types: legislative, supervisory, appointment and removal, and decision-making on major issues (the so-called

“Four Powers”). This conceptual division is attributed to Peng Zhen (in an important speech given in 1980) and has been kept in use by scholars in China. The evolving relationship of the resolution power to the other three parliamentary powers has gone through two periods.

1982-2013: the Resolution Power depended on the exercise of the other powers

PCs’ Resolution Power was written into the Chinese Constitution in 1982. However, from 1982 to 2013, the central roles of PCs were seen as performing their legislative and supervisory functions. Under the leadership of Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, resolutions were only used to render decisions related to legislative and supervisory procedures. Moreover, Jiang and Hu gave consistent emphasis to the legislative and supervisory powers of parliamentary bodies, relegating the resolution power to far lower prominence. For instance:

- On March 18, 1990, at the Third Session of the 7th National People’s Congress (NPC), Jiang Zemin stated that those important decisions of the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee that should be decided by the NPC must be submitted to the latter to go through the legal process so as to become the will of the state. The same principle should apply to subnational PCs. He then emphasized improving the functions of PCs, especially strengthening their legislative and supervisory

- On September 12, 1997, in the report to the 15th Party Congress, Jiang Zemin stated that it was necessary to integrate legislation with policy decisions on major issues in reform and development.

- On November 8, 2012, in the report to the 8th NPC, Hu Jintao reaffirmed that, in order to turn the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) proposals into the will of the state, PCs’ functions as the organ of state power need to be fully utilized, which involves the exercise of the powers of legislation, supervision, appointment and removal, and decision-making. He then emphasized legislative and supervisory work in particular, again leaving the resolution power to lower status.

Indeed, prior to 2013, Hu was the only CCP General Secretary who mentioned the four powers of PCs as a whole. Emphasis instead was reserved for legislative and supervisory powers. After the 7th NPC, NPC Chairmen also seldom talked about the Resolution Power in public speeches, especially compared to the other parliamentary powers. PCs used the resolution instrument in relation to legislative activities mainly when they amended or repealed previous statutes. Newly enacted statutes generally assumed the names of ordinances (tiaoli) and measures (banfa).

2013-present: the Resolution Power was promoted to an unprecedent height

On November 12, 2013, the Third Plenum of the 18th NPC published the Decision on Major Issues to Comprehensively Deepening Reform. While this lengthy announcement was extensively parsed at the time for understanding Xi Jinping’s approach to law, one sentence buried in it eluded little attention. The Decision proposed to “improve the system of discussion and decision-making on major issues in People’s Congresses; governments at all levels shall report to the PC at the same level prior to making decisions on important issues.” As it turned out, this sentence heralded the entry of the parliamentary resolution power into political light, after decades of near invisibility.

In January 2017, the CCP General Office circulated a document titled “Implementation Opinions on Improving the System of Discussing and Decision-Making on Major Issues by People’s Congresses, and Reporting to People’s Congresses at Their Levels before Issuing Major Government Decisions” (《关于健全人大讨论决定重大事项制度,各级政府重大决策出台前向本级人大报告的实施意见》). This document was not made public, but as can be inferred from the lengthy title, there were two separate ideas: first, developing an institution for discussing and deciding on important policy issues within parliamentary bodies; and second, strengthening the practice of requiring the executive branch to report to PCs at same level before making major decisions.

- Instituting parliamentary discussions and decisions over important issues (apart from legislation)

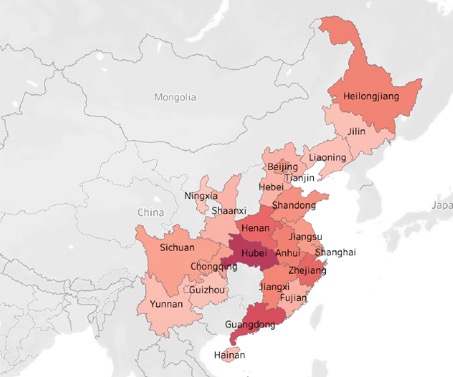

Since the 2017 CCP Implementation Opinions, among the 28 provincial PCs that already had procedural statutes regarding “discussing and decision-making on major issues” (DDMI), 17 amended such statutes, where they elaborated the scope of “major issues” in conformity to the Implementation Opinions and introduced further procedural details. Beijing, which had no DDMI statute before, also enacted one in 2017.

Notably, Article 16 of Zhejiang’s DDMI statute and Article 4 in Hubei’s DDMI statute both provide that Resolutions adopted according to DDMI procedures have the effect of law. That is, these provisions assert that PC resolutions possess the same effect as local statutes recognized under the Law on Legislation. Since 2017, the Zhejiang Provincial PC has passed three Resolutions regulating individual obligations directly. By contrast, there were no such Resolutions before 2017.

- Requiring the executive branch to report to local PCs at before major policy decisions

In the past three years, five provincial PCs in China (Zhejiang, Anhui, Sichuan, Hubei and Guangxi) have introduced rules in their DDMI statutes that the executive branch should report to PCs at the same level before making decisions on major issues. In October 2018, the Beijing People’s Government released an informal document prescribing the policies that it would itself follow for reporting to the Standing Committee of the Beijing PC regarding major policy decisions.

On February 25, 2019, Xi Jinping presided over the second meeting of the Comprehensively Governing the Country by Law Committee. The meeting approved the Interim Regulation on Major Administrative Decision-Making Procedures (Draft), which was issued later by the State Council on April 20, 2019. Article 8 of this Regulation stipulates that when major administrative decisions fall within the scope of matters required by law to be deliberated and decided by the PC at the same level, or when there is a specific legal requirement for reporting to the PC, the “relevant procedures shall be followed.”

It is likely that the “relevant procedures” referred to here are to come from local DDMI statutes. Currently, with the exception of Xinjiang and Ningxia, all provincial PCs have issued DDMI statutes and listed the scope of major issues, based on the Local Organizational Law and the 2017 CCP Implementation Opinions. If a matter fits into the category of “major issues”, PCs can adopt Resolutions independently, while the executive branch can also make policy decisions. In the latter case, the executive branch should report to the PC at the same level and obtain approval before issuance of the policy.

As a result of these developments, the Resolution Power of Chinese parliamentary bodies has been promoted to an unprecedented height, in some ways even above the legislative and supervisory powers. PCs in prefectural cities may issue Resolutions with legal effects directly under DDMI statutes. If they opt for this procedure, cities can avoid submitting draft legislation to the provincial PC for approval before it comes into force (as provided in the Law on Legislation). Just as remarkably, there seems to be acceptance that PCs at the county level, while possessing no legislative power based on LL, can pass Resolutions on major issues with the effect of law in their jurisdiction. In short, insofar as major policy issues are concerned, there appears to be an emerging view that DDMI statutes preclude the application of the Law on Legislation, relax the procedural strictness on parliamentary lawmaking in lower-level PCs, and thereby grant extensive flexibility and discretion to these bodies.

References

Institute of Theory on China’s People’s Congress System Decision-making Power of People’s Congress under Different Concepts, 中国人民代表大会制度理论研究会,《不同概念下的人大决定权》,专题探讨。

Sun Ying (2019), On the Dual Attributes of Decision-Making power of People’s Congress on Major Issues, Politics and Law, no. 2, p. 33, 孙莹,《论人大重大事项决定权的双重属性》,《政治与法律》2019年第2期, 第33页,

Follow

Follow