Written By: Jeff Hicks and Max Norton

Assisted By: Joanne Xu and Yi Zhao

Posted: February 23, 2021

By mid-March, 2020, many Canadians had come to recognize the COVID-19 pandemic as a once-in-a-lifetime crisis that could cause permanent changes to their lives. Just as online classes immediately began to transform the experience of legal education, academics also shifted their attention to the enormity of the challenges brought by COVID. The Centre for Asian Legal Studies organized a COVID-19 Roundtable on March 5. In the ensuing months, faculty members and students together pursued multiple strands of research on COVID’s impact on law and governance in Asia.

You can find some examples of student research in this area at the CALS blog: topics ranged from changes in Canadian immigration policy, international competition and coordination in vaccine research, to novel uses of parliamentary power in China during pandemic times. Many of these research projects are still ongoing, and we would be very interested in feedbacks from readers of this newsletter.

One example that illustrates our research on governmental responses to COVID is a working paper jointly authored by Jeff Hicks, Max Norton (both Ph.D. students at UBC’s Vancouver School of Economics (VSE), and Wei Cui (Allard law and CALS member). The paper, titled “How Well-Targeted Are Payroll Tax Cuts as a Response to COVID-19? Evidence from China,” studies the most substantial piece of economic policy that the Chinese government adopted in response to the COVID shock—a payroll tax holiday made available to almost all firms in the country. Not only is the policy important, a large and unique dataset we used to carry out the study also enabled us to make findings otherwise infeasible.

On February 20, 2020, China’s Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security (MOHRSS) announced that for the period between February and June, all businesses other than the largest (less than 1%) of firms were completely exempted from the obligation to make employer contributions to three components of China’s social insurance (SI) regime: pension, unemployment and injury. The remaining large businesses as well as private, non-business employers received a 50% reduction in contribution obligations for 3 months (February-April). In June, MOHRSS extended the exemption for the first group of firms to the end of 2020, and the 50% reduction for the second group firms to June. Separately, on February 21, 2020, China’s Nation Healthcare Security Administration announced guidelines for mitigating employer contributions for medical insurance (MI)—the second largest component in China’s SI system after pension insurance. Under these guidelines, local jurisdictions may reduce employer MI contributions by up to 50%, for 5 months (February to June).

These tax holidays represent a response to COVID that is large both in aggregate terms and for each firm beneficiary. The government estimated that the foregone revenue to the nation’s pension systems alone exceeded CNY 576 billion by the end of June. The entire fiscal cost for 2020 could easily surpass CNY 1 trillion (CAD 200 billion)—which would be larger than the projected combined costs of the Canada Emergency Response Benefit and Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy programs. For many employers, the policies brought a tax cut that was more than 20% of the wages paid. At least at first glance, these policies should improve the cash flow and the probability of survival for businesses, support job retention, and even facilitate the hiring of new workers.

A distinctive feature of our study is the use of confidential taxpayer data from one large Chinese province. We use this data to simulate the impact of China’s 2020 payroll tax cuts, and this approach carries a critical advantage. Not only does China have no national SI regime, even China’s provinces do not have their own unified SI systems. Pension insurance is often pooled at the prefectural level, and MI may be pooled at even lower, county levels. This means that when provinces report their SI budgets to the national government, they are aggregating budget reports generated by cities, which in turn are aggregating budgetary reports by counties and other lower units. The more layers there are in this aggregation process, the more information is lost. In contrast, comprehensive firm-level data gives both researchers and policymakers a more detailed, ground-up view of the impact of changes in SI policies.

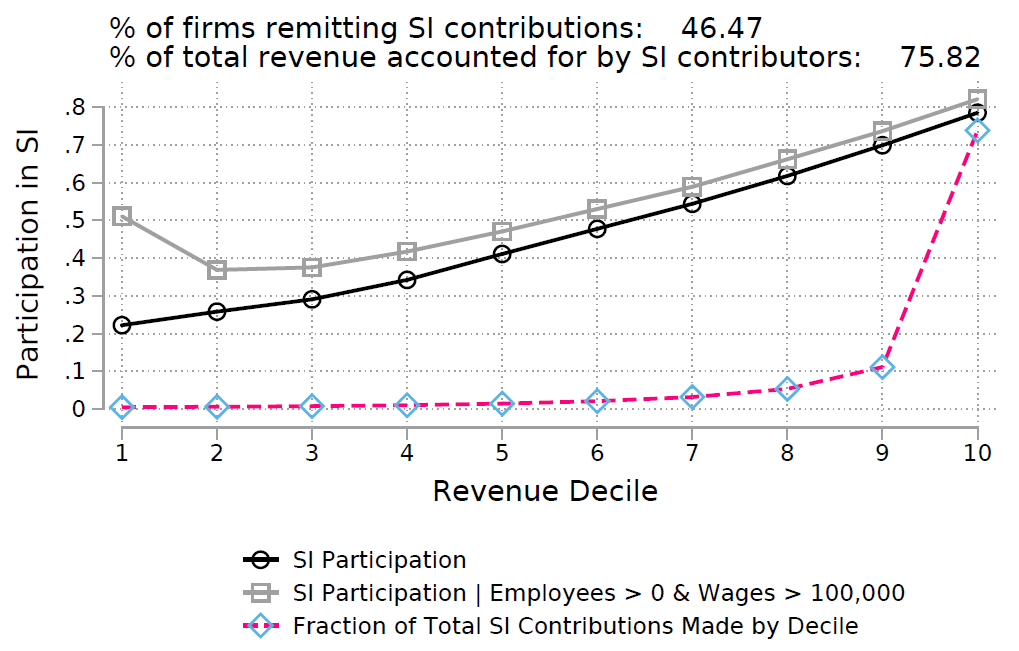

Our first finding is directly attributable to this data advantage. Our firm-level data covers both firms that participate in SI and those that do not. We observe that as many as 54% of active firms—representing 24% of aggregate economic activity—do not participate in SI at all. Therefore, they stand to receive no government support from the 2020 tax cuts. Moreover, non-participation is far higher among small firms: only 22% of the smallest decile of firms make SI contributions compared to 78% of the top decile (see Figure 1). This means that the payroll tax cut would be unable to deliver benefits to a vast population of small firms that engage in informal labor practice (in the sense that they do not offer their employees SI benefits.)

Figure 1 SI Participation Is Very Low among Small Firms in China

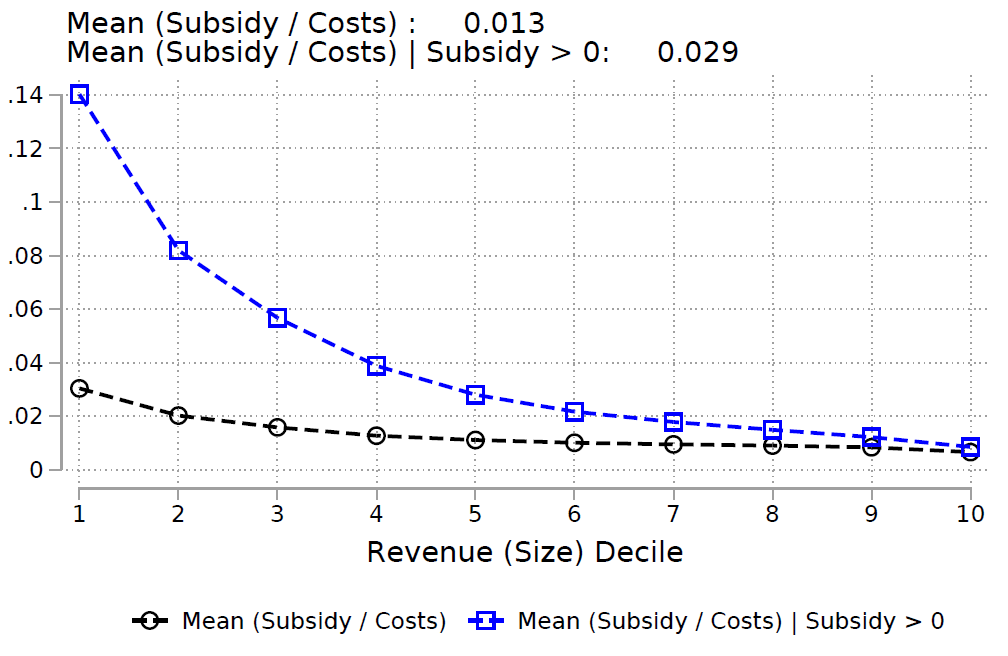

Despite this fundamental limitation of the policy, we find several forces that push in the other direction and give rise to desirable targeting properties. The first has to do with the fact that small firms tend to be more labor-intensive than large firms: their wage bills represent a larger portion of their total costs. Consequently, a payroll tax cut delivers greater benefits to smaller firms relative to total costs. On average, firms that participate in SI receive benefits equal to 1.3% of annual business expenses. But among the lowest decile of firms that participate in SI, the subsidy rises to 14% of annual expenses. This is approximately 20% of cash holdings the median small firm has on hand.

A second force that improves targeting is the regressive tax structure of China’s SI scheme. When an employer pays SI premia with respect to an employee, the employee’s wage is assumed to be no lower than 60% of the local average wage. This floor on employer premia means that the effective tax rate of the premia is very high for low wage workers. Meanwhile, employers are assumed to pay wages no more than 300% of the local average wage, which means that hiring workers for higher wages generate no additional SI premium expense. By suspending this system, the payroll tax holiday delivers more benefits to firms that hire low-wage workers—which tend to be more affected by the COVID crisis.

These first two forces combine to allow China’s payroll tax cuts to deliver greater benefit (relative to business expenses), as can be seen in Figure 2. In fact, even when non-participating firms that receive no benefits at all are included (as represented by the grey line in Figure 2), the smallest firms receive on average greater benefits as a fraction of their total costs.

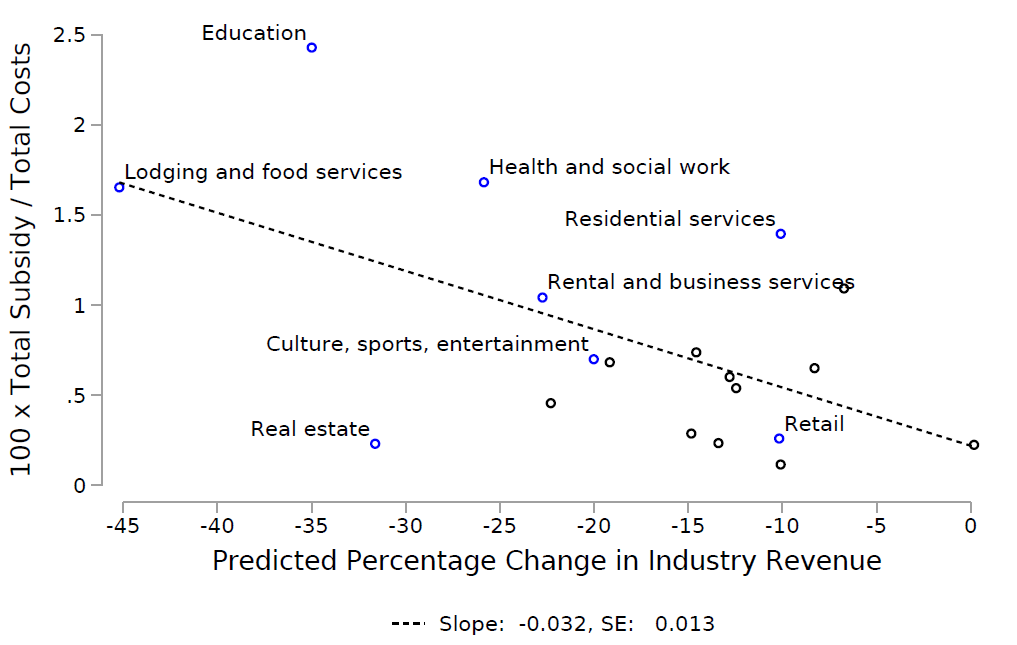

Finally, we find that many industries that are most negatively affected by COVID-19 also tend to be more labor-intensive. This pattern is illustrated by the hospitality, education, and culture and entertainment industries, and we verify it partly by drawing on results from a recent study conducted by researchers at Tsinghua University. For this reason, the SI tax cut also delivered a greater benefit (as a proportion of businesses’ operating costs) to industries that are more exposed to the economic downturn (see Figure 3).

Figure 2 Payroll Tax Cuts Deliver Greater Benefits to Small Firms on Average

Figure 3 The Payroll Tax Cut Delivered Greater Benefits to Vulnerable Industries

Students who participated in this research project included not only the two co-authors named above but also research assistants Joanne Xu and Yi Zhao who gathered important data and legal information. Indeed, without the effort of our talented students, many of the research projects would not be feasible. Your feedback on our research will thus not only constitute welcome advice to our faculty members but also especially contribute to our student training.

Follow

Follow