I was introduced to L. Dee Fink’s integrated course design worksheets when I took a UBC professional development course on Teaching in a Blended Learning Environment. I have really enjoyed using his approach to course design, because it asks you to think about learning goals and learning activities in ways far beyond just thinking about what content students should leave the course knowing. He asks you to consider learning goals in areas such as:

- Caring goals: developing new feelings, interests, values

- Human dimension goals: what they should learn about themselves and others

- Learning how to learn: how will their work in this course help them to learn better in the future?

… among many others.

He also has you start with the learning goals, and then think about content and activities in the course, which seems to me the right way to go about doing things. I used to (and still feel the pull to) start with content and the types of assignments I’d have, and then base the learning goals on those. But of course it makes sense to start off with what you’d like the students to learn, to be able to do, and then have that guide the rest.

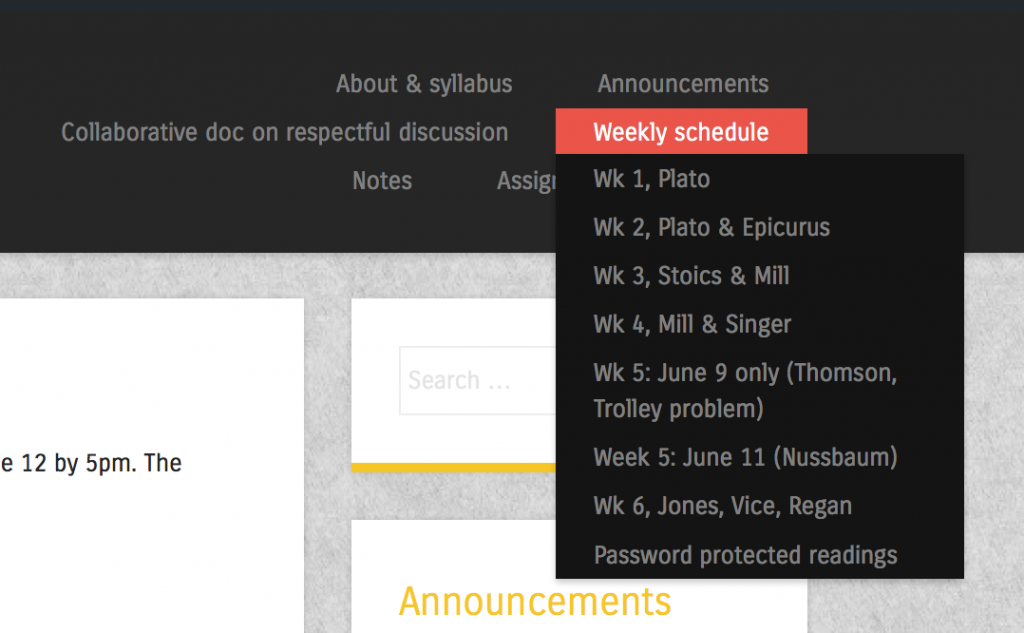

I’m working on redesigning my Introduction to Philosophy course, which is a one-term course focused on value theory–anything having to do with ethics, or social and political philosophy, or aesthetics. I have tried several different themes in the past and haven’t really been happy with any of them. This time I’m trying a kind of “life and death” theme, focused on what some philosophers have said about how we should live, and what we should think about death.

I have gone through the process of using these worksheets on this blog before, but this time I am using Workflowy, on the recommendation of Paul Hibbitts. He pointed out to me how easy it is to share parts of your Workflowy lists with others (so they don’t have to see all of what you’re working on, but just the stuff that’s relevant to a particular audience). The free version gets you quite a lot; I’ve been using it for awhile and haven’t run up against the limits to the free version yet. It’s not big on style, and it seems like it wouldn’t be that useful, really, until you get into using it and see the power of zooming in and out of your documents/lists. It’s like being able to go to a particular part of a very long document really easily and ignoring the rest.

Now, I wish I could embed this Workflowy list into my blog post, because then you could see the changes as I update it. But for now, this will have to do.

Here is my working through of Fink’s worksheets for my Introduction to Philosophy course: https://workflowy.com/s/mnpuEmtnAu

And here is a copy of what I’ve done so far, just copied and pasted from that Workflowy list today. I’d welcome any feedback you have!

Starting to work through the course design worksheets on Workflowy

- Situational factors to take into account when designing the course

- students--what do they tend to be like? prior experience with philosophy? attitudes towards the subject?

- most tend to have little or no prior experience with philosophy; few know what philosophy is

- most tend to find the readings very challenging

- some think that works in the history of philosophy are not relevant to their everyday lives; they prefer the more recent works

- mostly first and second-year students, so many of them are new to UBC (esp. since this is first-term course)

- most taking lots of courses, and/or working alongside their studies; they generally have too much to do and not enough time, so often stressed

- number of students, physical meeting space, structure of the weekly meetings, etc.

- max 150 (currently 136 enrolled)

- large lecture hall, with tables and immovable chairs: https://ssc.adm.ubc.ca/classroomservices/function/viewlocation?userEvent=ShowLocation&buildingID=LSK&roomID=200

- will be somewhat difficult to do small groups b/c can’t move chairs around; tried small groups in a room like this in the past and it was difficult

- 2 50-minute classes per week with all students; each student also part of one 50-minute discussion section with 25 students and a TA (I run one of these)

- the course–particular departmental or institutional requirements?

- not required for majors, so there is no particular curriculum that must be followed, no philosophers that have to be discussed, etc.

- focused on value theory: ethics, social and political philosophy, aesthetics, the meaning of life, the good life… anything in one or more of those areas

- should just introduce students to such topics and get them interested in philosophy if possible, maybe draw in to take more courses (or just get a decent sense of what philosophy is like and then they may never take another philosophy course again)

- special pedagogical challenges of the course

- making philosophy interesting and relevant to newcomers without sacrificing rigor

- exemplifying what philosophers do in a way that makes it seem like something useful for all of us, while still showing how difficult and complex it can be

- for me, showing the value of reading and discussing people like Plato, Epicurus, Mill to those who find them just old and no longer relevant

- why are works in the history of philosophy still important to read and talk about? Why not just read stuff from the last 50-100 years?

- making philosophy interesting and relevant to newcomers without sacrificing rigor

- students--what do they tend to be like? prior experience with philosophy? attitudes towards the subject?

- Learning goals #LOs

Fink suggests thinking about learning goals in several categories, noted below- Foundational knowledge: what key information or ideas, perspectives are important for students to learn?

- This is a tough one because of the nature of the course: there is no specific curriculum or set of information that must be taught in the course. But there are still some things I think they should know by the time they finish the course.

- What is an “argument”? They should be able to outline an argument in a philosophical text, identifying premises and conclusion, and be able to evaluate it effectively.

- They should come out of the course with an understanding of:

- What an “examined life” is, acc. to Socrates, the Socratic method

- Some of the basic arguments of Epicureanism and stoicism, existentialism, utilitarianism, Nussbaum’s “capabilities” approach

- [The following is for an earlier version of the course, for when I thought I might focus it on the philosophy of happiness] Name and explain three approaches to the philosophical study of happiness (e.g., hedonism, desire satisfaction, eudaimonism…what else?) and correctly connect one philosopher to each

- [The following is for an earlier version of the course, for when I thought I might focus it on the philosophy of happiness] Explain how philosophers study happiness as distinguished from empirical, psychological research, and say why the philosophical approach is also valuable.

- Application: what kinds of thinking are needed, such as critical, creative, practical? What sorts of skills do they need to learn?

- critical thinking (analyzing and evaluating): analyzing and evaluating arguments in the texts, and arguments by themselves and peers

- creative thinking (imagining and creating): come up with own criticisms of arguments and better ways to approach the issues; come up with creative solutions to ethical problems discussed

- practical thinking (solving problems and making decisions): take what they understand about sound argumentation and apply it to their own arguments, whether oral or in writing; also do so with the arguments of their peers in class or in peer feedback on writing

- skills

- being able to outline and evaluate arguments by others in the readings, as noted above

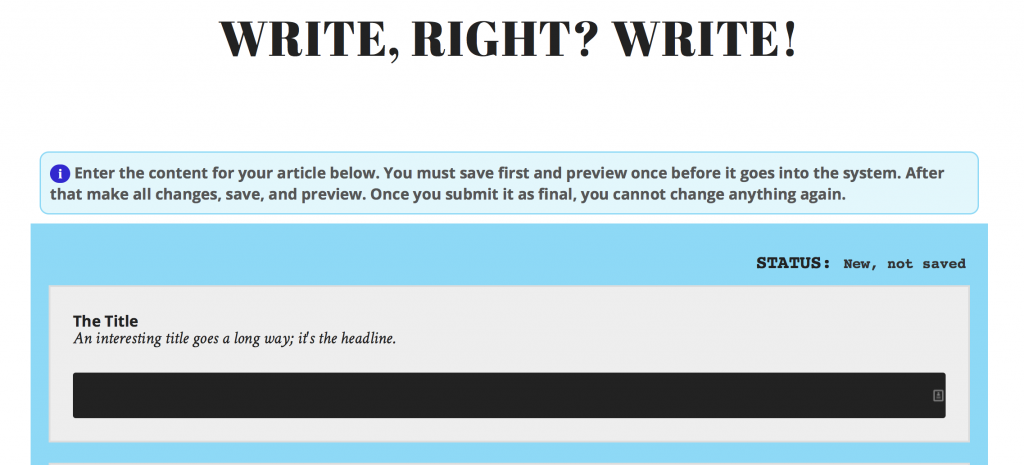

- write their own arguments, in various formats such as informal blog posts and formal essays

- evaluate arguments and writing by their peers, as a means to help improve their own writing

- Integration: what connections should students make between parts of the course? between what’s in the course and other areas, such as their own lives?

- It would be great if they could see why philosophical thinking about many issues is valuable

- What is philosophical thinking/activity and why is it useful more generally?

- How do they already do philosophy in their university studies or other parts of their lives?

- How might philosophical thinking be good for them to continue in the future?

- I don’t think it’s required, but it would be nice if the things we’re studying affected their own views of what a “good life” is, and had an impact on how they live their own lives

- They should be able to understand how the various approaches to “living well” and approaching death well differ, the strengths and weaknesses of each vis-à-vis the others

- It would be great if they could see why philosophical thinking about many issues is valuable

- Human dimension: what should students learn about themselves? about interacting with others in the future?

- It would be good if they learned the degree to which they tend to rely on unexamined beliefs and values in their thoughts about happiness (and other things, potentially), and why it might be good to examine those

- Learn that philosophical activity is something that they can and already do in their lives outside of class

- Learn the value of respectful, philosophical (or other) dialogue with peers–how can we engage in dialogue that respects everyone and yet moves forward rather than sitting with everyone’s differing opinions and not going anywhere out of fear of offending anyone?

- Caring: what changes would you like to see in what students care about? In their interests, values, feelings?

- I would like them to care about careful, philosophical inquiry, argument and dialogue, about how such activity can be helpful in addressing disagreements, if done well

- Care about whether their own views and values have been examined, whether they can provide adequate arguments for them, and what to do if they think they can’t

- Care about whether their own arguments for “big questions” like happiness or the good life are sound

- Care about treating with respect those whose views differ from theirs, but not thinking that this must mean we have to be relativists, that there are no objective truths about value

- Learning how to learn: what would you like students to learn about how to learn well in this course (and beyond)? how to become self-directed learners, engage in inquiry and knowledge construction?

- learn the value of working together with peers to learn; that sometimes learning on one’s own works well, and sometimes it’s also valuable to learn with peers

- learning with and from peers is not a waste of time compared to getting info from the prof as expert

- recognize that even when they feel they know more than others, “teaching” others is a very useful way to better understand something; we learn by helping others to learn, not just by getting information from them

- learn how to take notes on the main points of complex, philosophical texts

- learn what to do if something isn’t making sense; what options do they have for getting help? How can they avoid just being confused and not doing much to solve the problem?

- recognize the importance of writing and rewriting, that a first draft of a piece of writing is usually not the best, and revising to create new drafts is important

- understand that philosophical texts may require more than one read to understand them well

- learn the value of working together with peers to learn; that sometimes learning on one’s own works well, and sometimes it’s also valuable to learn with peers

- Foundational knowledge: what key information or ideas, perspectives are important for students to learn?

- Draft learning objectives developed from the above #LOs

These don’t address all of the goals above; some of those goals are addressed in what we’ll be doing in the class, but don’t show up specifically as objectives- For reference, LO’s from PHIL 102, Summer 2015 syllabus (this version of the course was on a different topic)

- 1. Give an answer to the question (one of many possible answers!): how would you describe what (Western) philosophy is, what philosophers do, and how such activities might help to make people’s lives better, based on your experiences in this course? (“philosophy in the world” assignment)

- 2. Explain at least one way in which they engage in philosophical activity in their lives outside this class (“philosophy in the world” assignment).

- 3. Explain the basic structure of an argument–premises and conclusion—and outline an argument in a philosophical text (argument outlines, final exam)

- 4. Assess the strength of arguments in assigned texts, in oral or written work by other students, and in their own writing (argument outlines, essays, peer review of other students’ essays, group discussions)

- 5. Participate in a respectful discussion with others on a philosophical question: clarify positions and arguments from themselves or others, criticize flawed arguments, present their own arguments, and do all this in manner that respects the other people in the discussion (small group discussions)

- 6. Write an argumentative essay that outlines and evaluates the views of other philosophers (essay assignments).

- 7. Explain how at least two Western philosophers might answer the question: what is philosophy/what do philosophers do, and how might it help make people’s lives better? (essay assignments)

- For reference, LO’s from PHIL 102, Summer 2015 syllabus (this version of the course was on a different topic)

- Draft Learning Obj’s for this course: Students who successfully complete this course should be able to:

- 1. Define and explain at least two philosophical approaches to how we should live (such as Epicureanism and Stoicism) and give the name of at least one philosopher who espouses each. Explain the similarities and differences between those approache sand evaluate each.

- 2. Explain the utilitarian approach as well as the capabilities approach to how we should help others to live well, and give the name of at least one philosopher associated with each. Explain similarities and differences between these approaches and evaluate each.

- 3. Explain the basic structure of a philosophical argument–premises and conclusion—and outline an argument in a philosophical text

- 4. Assess the strength of arguments in assigned texts, in oral or written work by other students, and their own arguments (oral or written)

- 5. Participate in a respectful discussion with others on a philosophical question: clarify positions and arguments from themselves or others, criticize flawed arguments, present their own arguments, and do all this in manner that respects the other people in the discussion

- 6. Produce a polished piece of philosophical writing, with a sound argument, strong evidence, and clear organization

- 7. Read a complex philosophical text and take notes that distinguish the main points of the arguments therein.

- 8. Based on what we’ve studied in the class, give one (of many!) possible answers to the question: What is philosophical activity and why might it be useful? How do you engage in philosophical activity outside this course?

- Assessments to fit these objectives (TBA)

- teaching and learning activities to fit these objectives (TBA)

- consider whether the parts of the course are integrated (TBA)