WEBLOG #2

Revision of intent

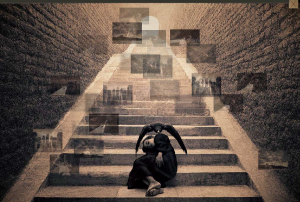

As a result of my readings in reference to this weblog and recent course readings, I would like to revise my area of intention regarding my research. Instead of focussing on how technology can be used to connect Indigenous students to their cultural context within a learning framework, I would like to focus on a process that helps them put technology into a cultural context thereby enabling them to make informed and negotiated decisions about its use in their communities and lives. This type of education around technology, its origins, myths, basis in westernized values, etc. can inform and, in so doing, liberate Indigenous youth, and others, from further colonization by the “white” use of technology. This process would also provide them with a voice in the social negotiation of where technology has come from and where it will go. I would like to point out that, for now, my proposed plan would include education of all youths or adults within an integrated classroom and would provide an unfolding of information and discussion before jumping into Indigenous perspectives and how their lens may provide a beneficial angle from which to view technology.

1st Post

Dei, George J. Sefa. 2000. “Rethinking the Role of Indigenous Knowledges in the Academy.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 4(2):111–33. Retrieved from http://www.nall.ca/res/58GeorgeDei.pdf.

This paper addresses the many issues facing the critical examination of the definition and operationalization of Indigenous knowledge in academic institutions, also referred to as a process of academic decolonization. With the advent of the information age and globalization leading to more and more dominant flows of Euro-American perspectives, it is all the more important to bring Indigenous knowledge into Euro-American institutions of power to prevent an imbalance of knowledge dissemination, generation and discussion. Indigenous knowledge is encapsulated by the author as “the common-good-sense ideas and cultural knowledge of local people concerning the everyday realities of living” and is generated through “social interpretations of meanings and explanations” which are “holistic and relational” and not “individualized and disconnected into a universal abstract” (p.5). When considering the discursive approach to understanding Indigenous knowledges within dominant academic institutions, the anti-colonial approach is perceived by the author to be the most effective means to discussing the differences and connections between the knowledges. Anti-colonialism “interrogates the power configurations embedded in ideas, cultures and histories of knowledge production and use. It is an epistemology of the colonized, anchored in the indigenous sense of collective and common colonial (‘alien, imposed and dominating’) consciousness. This approach also “offers a critique of the wholesale degradation, disparagement and discard of ‘tradition’ and ‘culture’ in the interest of so-called ‘modernity’, ‘individualism’, and the ‘global space’. Overall, the author advocates the continued critical and oppositional approach to the destabilization of Eurocentric knowledge, ‘as the only valid way of knowing’, in order to create incremental but cumulative changes to the institutional knowledge frameworks. But he cautions against cynicism that would claim the right to discrete and pristine spaces for indigenous knowledges, outside of institutions and the effects of other knowledge, that would act to marginalize Indigenous people and their knowledge from a critical collective and academic discourse on knowledge [need to creolize]. As a final note on this article, the author cautions against certain problems regarding knowledge representations as contributing to false and unproductive discourses on Indigendous knowledge within a global framework:

- difficulty in defining an authentic voice “who has discursive authority on Indigenous knowledges, in other words, how do we define the ‘real past’ and the group’s cultural identity? (p.12)

- representation of Indigenous knowledges as “fixed and static outside site and space removed from practice, performance, power, and process” (p. 15)

- “fetishized representations of Indigenous culture and identity” (p.14)

- “‘exoticization’ of cultures and traditions” (p.14)

- “selective [mis]capturings of elements of their past, histories, and traditions” (p.13)

- and finally, the author questions the loss of meaning in storing Indigenous knowledge, specifically, orality as ‘text’ or ‘recorded sound’ outside of their given contexts. (p. 15)

2nd Post

Johnson, J., & Murton, B. (2007). Re/placing native science: Indigenous voices in contemporary constructions of nature. Geographical Research 45, 121–29. Retrieved from http://faculty.washington.edu/pembina/all_articles/Johnson2007.pdf

In “Re/placing native science: Indigenous voices in contemporary constructions of nature”, Johnson and Murton discuss the dominance of the western Euro-American perspective and the need to insert the Indigenous voice into these dialogues. From the days of Kant, Descartes and the European enlightenment, Euro-American thinking has been dominated by a knowledge system that disembodies humans from the order of the world in an objective process that attempts to express the “universal truth” of things. The authors, claim that this objective European taxonomy and systematizing of nature, in which specimens are removed from their place in their ecological systems, and other people’s economic, historical, social, and symbolic systems and are reordered in European patterns of order, has led to the wholesale alienation of the Indigenous approach to knowledge. One Indigenous author, Gregory Cajete (cited in Johnson & Murton, 2007), describes Native science as ‘a lived and creative relationship with the natural world … [an] intimate and creative participation [which] heightens awareness of the subtle qualities of a place’ (p.1). Each of these narratives represents an ideology which, through the voices of many different perspectives, can be shared, challenged, negotiated and rewritten to better suite humanities social, scientific, technological and cultural needs. Unfortunately, Makere Stewart-Harawira (cited in Johnson & Murton, 2007), observes, ‘outside of Indigenous scholarship itself, within academic circles little serious attention has been paid to examining the possibilities inherent in Indigenous ontologies. In the context of the previous article of this blog, if the global society is to prevent an imbalance of power in knowledge systems, it must be willing to analyze the current Euro-American approaches to knowledge and include different counter-narratives as both a way to understand possible bias and represent different perspectives.

3rd Post

Dinerstein, J. (2006). Technology and Its Discontents: On the Verge of the Posthuman. American Quarterly, 58(3), 569-95. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/40068384

Dinerstein, in “Technology and its discontents: On the verge of posthuman”, asks how is it possible to think about technologies outside of a western framework? In this article, Haraway (cited in Dinerstein, 2006) recognizes the need for a more “imaginative relation to techno-science”…a call for new metaphors – such as trickster figures like the Coyote to “refigure possible worlds” by thinking outside of westernized views on techno-science. In essence the article discusses the history of techno-scientific thinking, westernized views on technology, and the “white” cyborg thereby suggesting the subsequent need for counter-narratives to transform the techno-cultural mythos.

The article addresses the very real need to confront issues like: What is progress for? and What is technology for? By turning towards an understanding of human kind as a “multiethnic, multicultural, multi-genetic construction created through centuries of contact and acculturation”, we can creolize the communication about technology and return to the concept of “social progress” instead of “technological progress”. This would add the feminist, Indigenous and minority voices to the technological discussion while diluting the “white male” legacies of colonialism, capitalism and idealized technological utopianism.

4th post

In Indigenous Perspectives on Globalization: Self-Determination Through Autonomous Media Creation, Rebeka Tabobondung, a Native America writer and creator of the online Muskrat Magazine, addresses concerns about Indigenous people, globalization and autonomy. She discusses how Indigenous communities might foster autonomy and self-determination through new media and combat the dominant westernized world view. She suggests that the domination and commoditization of land and people spawned by the “neo-liberal globalization” movement has resulted in a degradation of ecological, economic and social aspects of all of our lives, not just Indigenous peoples.

Unlike the mainstream media productions that promote the values and interests of the neo-liberal dominant world view, autonomous media provides an opportunity for Indigenous peoples to reconstruct media representations of themselves and become influencers of mainstream culture. Through autonomous media creation, Indigenous people will be able to create media that reflects their values, culture, aesthetics and diversity. But she worries that, despite its massive potential, if individuals limit themselves to passive consumption, globalization and destruction of other world views will continue.

She described Indigenous media production like a “contemporary talking stick” that enables sharing between people of stories, support, and space, even though separated by great distances. Ultimately, Indigenous cultures, myths and history will continue if kept alive in the minds and imaginations of the people as they share, define, reflect on the past, present and future of their community. And through the global reach of new media, she envisions a globalization that includes a sharing of world views that will benefit the entire planet and people.

When I first started this course, I saw the virtual online world as simulation and non-materialistic, something that couldn’t provide an authentic connection or replace in-place tribal interactions, but during my readings in ETEC 531, I began to see that these connections are as real as anything in front of me that I can pick up and touch. Just because we are creating understanding and connections in digital space doesn’t make it any less meaningful than F2F interactions. It has been this revelation that has given me a greater appreciation for the use of new media in Indigenous fight for autonomy, culture, and influence.

5th Post

Rebecka Tabobondung’s online magazine, Muskrat, covers everything from contemporary issues facing Indigenous urban peoples to more tradition discourse in which elders are consulted for their cultural knowledge. It demonstrates a modern use of media technology for the expression of urban Canadian Native American’s interests and discourse, while also educating outsiders in a very organic forum. It contains stories, art, recipes, insights, activism, blogs, links and more. Many of their articles include videos of Native American’s experiences, memories, and experiential insights.

As mentioned in the previous post, Rebeka provides a new media format that reminds me of a mainstreams Oprah magazine full of pictures, inspiration, relevant information, news, events, discourse, etc. Although, she provides a uniquely Indigenous aesthetics and design in her interviews in which she allows each person to tell their story without interruption….something I noticed in Michael Maker`s interviews which present a very different style than mainstream media.

Cheers, Steve