The Steele Springs Waterworks District (SSWD), north of Armstrong, has some water quality issues. A couple of representatives from the district, which supplies water to 58 households, recently presented an open letter to the Water Stewardship Council of the Okanagan Basin Water Board (SSWD 2014 05 Steele Springs Nitrate Story) . In brief, nitrate levels in the Steele Springs water source have reached a level that is above the 10 ppm that is considered safe for drinking water, and the people connected to the system want something done about it. I chatted briefly with friend and colleague Dr. Craig Nichol (Craig’s website), who pointed out that this is not the first time that Steele Springs has had issues, and a quick internet search reveals that Steele Springs has had boil water advisories in the past.

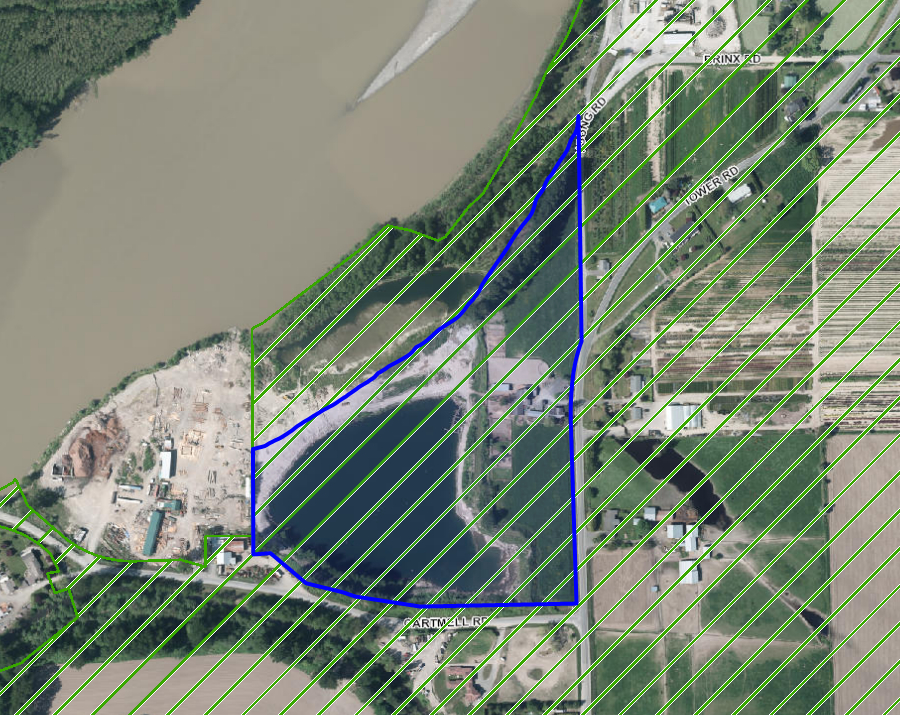

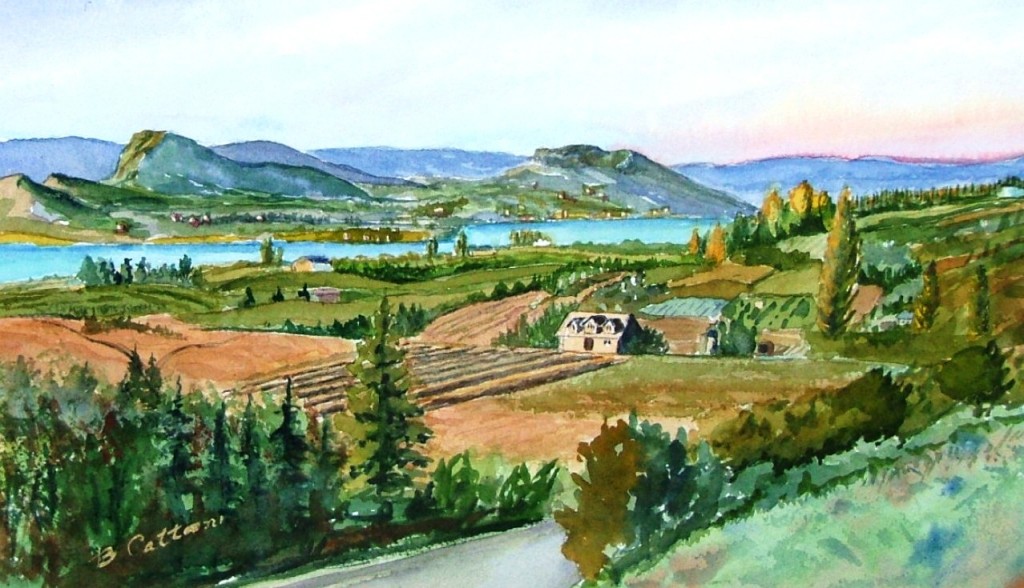

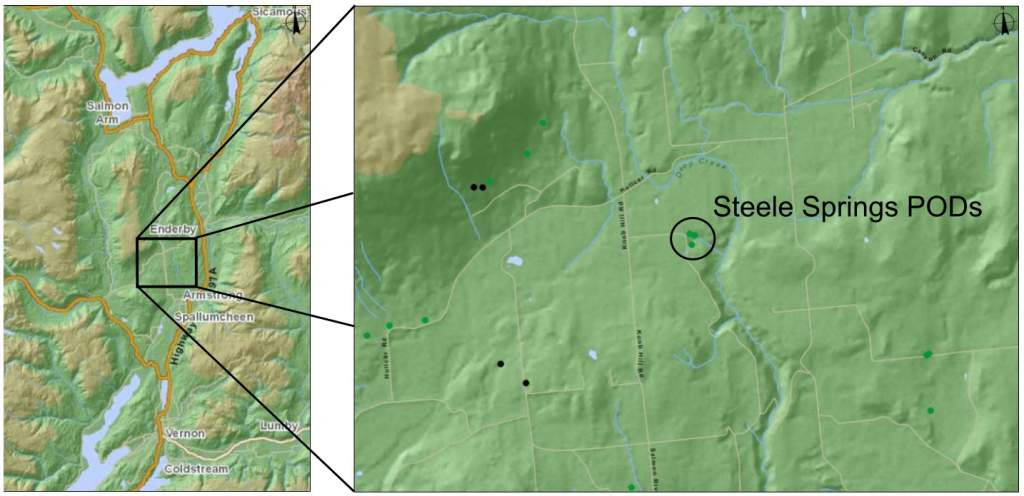

Where is Steele Springs? The SSWD has five water licences, the oldest of which was issued in 1894, all of which are attached to one point of diversion (POD). I used the provincial government’s mapping website (iMap BC) to find the point of diversion. I built the image below using information from this site. The district draws its water from a spring in the upper bank of a gully above Deep Creek.

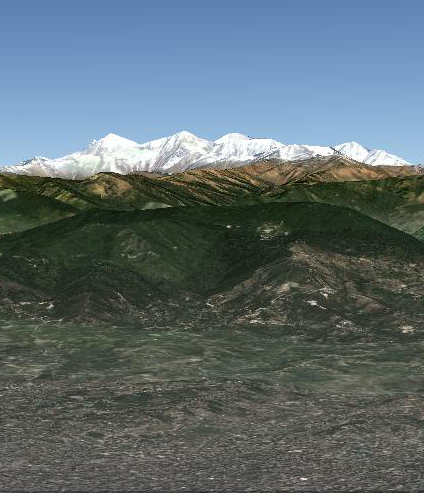

Another way to look at the location of Steele Springs is with a Google Earth(TM) image. The image below is a perspective image created by Google Earth. The gully through which Deep Creek flows and the location in the bank of that gully of the POD for Steele Springs stands out nicely. What also stands out is how much of the land around the water source has been developed for agriculture. Nitrate pollution of groundwater can be caused by animal waste being spread on the land, and the board of the SSWD feel strongly that this is the source of their water quality problems.

Another way to look at the location of Steele Springs is with a Google Earth(TM) image. The image below is a perspective image created by Google Earth. The gully through which Deep Creek flows and the location in the bank of that gully of the POD for Steele Springs stands out nicely. What also stands out is how much of the land around the water source has been developed for agriculture. Nitrate pollution of groundwater can be caused by animal waste being spread on the land, and the board of the SSWD feel strongly that this is the source of their water quality problems.

As an economist, I can’t comment on the validity of the case being made by the SSWD. My smattering of university science courses may lead me to speculate, but this matter is too serious for my naive speculations. What is known is that Steele Springs has high nitrate levels in the water, that spreading animal waste on the land can cause nitrate pollution of groundwater, that groundwater movement can transport pollutants from one location to another, and that groundwater movement can be relatively slow, meaning that waiting for pollutants in groundwater to be flushed out may take a while.

As an economist, I can’t comment on the validity of the case being made by the SSWD. My smattering of university science courses may lead me to speculate, but this matter is too serious for my naive speculations. What is known is that Steele Springs has high nitrate levels in the water, that spreading animal waste on the land can cause nitrate pollution of groundwater, that groundwater movement can transport pollutants from one location to another, and that groundwater movement can be relatively slow, meaning that waiting for pollutants in groundwater to be flushed out may take a while.

So, what should be done, and who should pay for it?

There are probably a number of things that could be done. Changing agricultural practices in the areas that are impacting Steele Springs is the solution that seems to be preferred by the SSWD. Can it be guaranteed that inappropriate agricultural activities won’t take place? Do we have enough information to know which agricultural practices on which areas of land are contributing to the problem? Is Steele Springs simply a vulnerable water source which will always be difficult to protect? Could the water be treated in some way to reduce nitrate to a safe level? Could SSWD tap a different water source, perhaps with a deep well or drawn from a location that is not as vulnerable to surface activities. Are there other utilities nearby that could share a source, perhaps sharing the costs? Could somebody (the regional district, the province, …) buy all the land that is potentially impacting on Steele Springs, and then rent it out with conditions on how it is used?

Moving to the who should pay question is where it gets complicated. Is it fair to force best management practices on some farmers and not others? Is it fair that some farmers, because of where their land is, have less freedom about how to manage their farms than others? Is it fair to change the rules, to tell a farmer who invested in a farm business that she can no longer farm the way she was planning to farm because we learned that to do so will impact on groundwater? Should we pay the farmer because we have taken this ‘right’ away from her, or should we just force her to change her practices, and bear the cost of doing so?

The BC Farm Practices Protection Act was created to protect farmers from nuisance lawsuits and local bylaws that could prevent a farmer from engaging in normal farming activities. Farming operations do generate noise, odor and other inconveniences. People unfamiliar with rural landscapes, particularly those new to such landscapes, can forget this and have sometimes made life difficult for farmers. Thus, the act. In effect, the act says that the non-farm community must bear the cost of dealing with the more unpleasant consequences of agricultural activities.

The BC Water Sustainability Act prohibits the introduction of a range of substances, including animal waste, into a stream or well. When mentioning wells, it speaks about substances entering one well impacting other wells or aquifers and streams that are connected to the well. This act seems to place the onus on the polluter to pay the costs of protecting surface waters and groundwater from pollution. So, does this mean that farmers who happen to be farming on land that impacts groundwater need to change their practices so that the groundwater is not impacted?

This leaves us with a conundrum. Steele Springs has a nitrate problem, and it will cost the SSWD a considerable amount of money to deal with this problem. Nitrates seem to be a new problem. For a water system that includes licences dating back over 100 years, it seems unfair that they have to pay to fix a problem that was not of their doing. The farmers, who may be contributing to the problem, do not seem to be doing anything that isn’t part of ‘normal farming practices’. Forcing one group of farmers to adopt more costly practices when other’s don’t have to also seems unfair. Is there a solution that is fair to all involved? I’m sure the SSWD, the Regional District of North Okanagan, and the agricultural community would all like to find one.

Follow

Follow