Within the Christian tradition, the apostle Matthew is credited with writing the following account of events during the last supper that Jesus shared with his closest followers.

Within the Christian tradition, the apostle Matthew is credited with writing the following account of events during the last supper that Jesus shared with his closest followers.

26 Now as they were eating, Jesus took bread, and when he had said the blessing he broke it and gave it to the disciples. ‘Take it and eat,’ he said, ‘this is my body.’

27 Then he took a cup, and when he had given thanks he handed it to them saying, ‘Drink from this, all of you,

28 for this is my blood, the blood of the covenant, poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins. (New Jerusalem Bible, Matt. 26.26-28).

I think these words exemplify the depth of the connection between food and community, a connection that is likely present in most cultures and traditions. Sharing food, especially food that we have had a hand in gathering, preparing or growing, is sharing a part of ourselves. Sharing food also plays a central part in healing the divisions between people and communities. The roll of sharing food in sustaining and strengthening community is rooted deep in our culture, if not in our genes. For most of human history, people existed in small, hunter-gatherer communities, where some in the community hunted and others gathered, and both came together to share what they had harvested.

I recently posted the argument that even though agriculture within the boundaries of Kelowna is not that significant to the local economy, global environment, or local food security, it produces many values beyond food that are important and therefore agriculture is worth supporting. I presented statistics gleaned from a variety of sources to back up my points. Some readers were outraged. They asserted that my facts were wrong, but when I inquired, could not produce anything that challenged what I had posted. I delved a bit deeper into the work that has been done on local food production and poverty alleviation and on local food production and environmental impacts. The point I made, that local food production isn’t automatically better for the environment or helpful for the food insecure in our community, isn’t challenged by any rigorous studies I could find. Why then is it so important to some people that these facts not be true?

http://youngagrarians.org/

Farming is hard. The Stan Roger’s song “Field Behind the Plow” brings tears to my eyes when I think of the hours I spent on a tractor in my youth, and of my father and his dedication to the farm. Farmers don’t have the luxury of a regularly scheduled job. Their work hours are determined by weather and season, and the plethora of unexpected things that must be dealt with. Farmers don’t have the luxury of a regular salary and a union negotiating on their behalf. Rather, they are stuck between the risks generated by the natural system with which they work and the risks from the market, a result of the way those natural systems have played out elsewhere in the world, changes in people’s tastes and preferences, and all the government policies that impact on agriculture around the world.

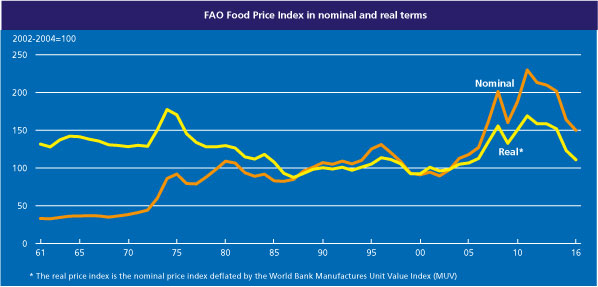

Global food prices have been on a downward trend for much of recent history. Over the last decade they rose for a number of years, peaking in inflation adjusted terms at more than 50% above the price level in the early 2000s. However, they have now come almost all the way back down to where they were, and they have come down as rapidly as they rose. There are a number of explanations for the rise, ranging from government support for biofuels that took land out of food production, rapid economic growth in China and increasing demand for meat and similar products that are further up the food chain, and events like droughts and floods. Why have they come back down? Farmers have taken advantage of the higher prices, and increased their production.

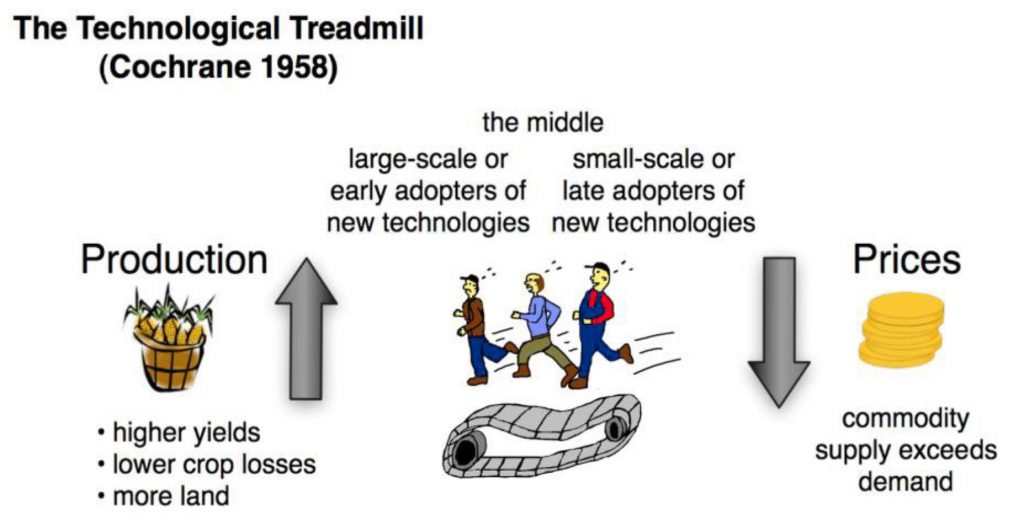

Farmer’s, and the industries that support them – fertilizer, seed, equipment, plant breeding, etc. – are very good at what they do. That food production has increased faster than the global population is a testament to how good the agriculture industry is at meeting global food demand. In fact, in some ways, they may be too good. It has long been noticed that in spite of improving technology, the situation of the average farmer doesn’t seem to get any better. Agricultural economist Willard Cochrane described this dilemma as a treadmill (nice presentation at www.aae.wisc.edu/aae320/AgPolicy/Treadmill.pptx). The elements of this treadmill are:

- A new technology emerges that lowers production costs.

- Early adopters (often larger farms) produce more and earn above normal profit.

- Extra output leads to lower market price, and lower profit or loss for rest of industry.

- Rest of industry forced to adopt. Further lowers price till all earning normal profit.

- Those unable to adopt exit the industry, typically selling to larger farmers.

- Consumers gain from lower food prices, farmers overall see no long term gain.

- Industry over time adjusts to fewer, larger producers.

http://www.osymigrant.org/Brief_Globalization-of-Food.pdf

So, farmers and the agricultural industry have done a remarkable job of feeding the population of the world. However, the average farmer hasn’t gained much as a result. Those who have done well tend to be the early adopters, innovators in trying out new technology, in exploring new marketing opportunities, etc. Those who can afford to do this also tend to be the larger farms, perpetuating the cycle favoring ever increasing farm size and ever shrinking share of the population involved in primary agriculture. All of this means that the return farmers have been getting on average for their labors and their investment hasn’t been increasing, while the share of the household budget making it to the farm gate has been steadily falling.

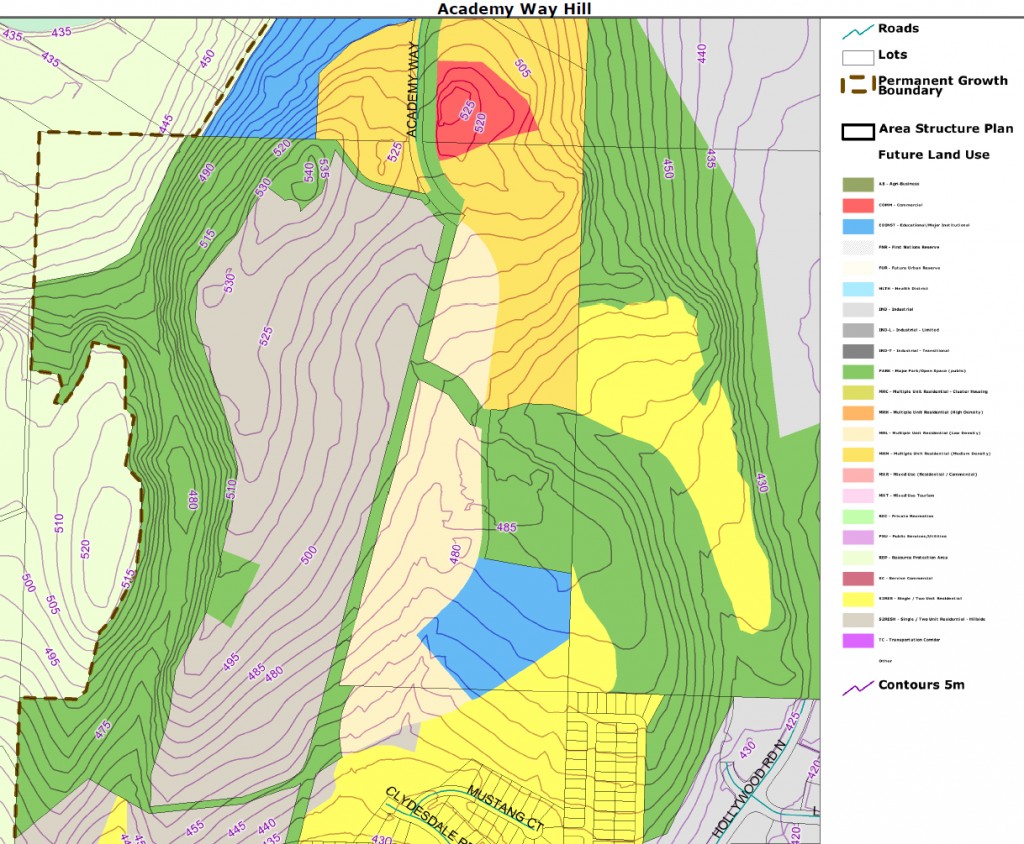

If that wasn’t bad enough, things get worse in places like Kelowna. Land in the urban fringe is land that can be used for something other than farming. A basic fact of property markets is that the price properties trade at depends on what they can potentially be used for, not what they are actually used for. Agricultural land in Kelowna has various potential uses, including rural estates and development. The Agricultural Land Reserve is an attempt to limit the development option, but growing cities need land, and the ALR has mechanisms to ‘exclude’ land. Those buying property know that there is potential to get it out of the ALR and are willing to pay more than the agricultural value of the land to buy into this potential. If a farmer wishes to purchase land in the urban fringe, she likely has to pay more than the land will ever pay back from the crop she can grow. This makes it very hard for anyone who wants to start farming to do so in the urban fringe. However, since it is costly to establish a farm, new farmers often need to be close to urban centers to hold down other jobs, jobs that enable them to finance their farm in the early stages. In Kelowna, it also means competing against ‘lifestyle’ farmers, who retire to the Okanagan and take up farming as a retirement project, with no real need to make a living from it.

http://vancouver.healthcastle.com/free-events-vancouvers-farmers-markets

So if making a living from farming in the urban fringe is hard and if there are alternative, more profitable uses for the land, why should we seek to protect agricultural land in Kelowna? In my last post, I listed a number of reasons, linked together with the idea of ‘multifunctionality’. The multifunctionality, the multiple functions provided, by agriculture is something we don’t always recognize, and I think that we can make poor decisions about land use if we don’t look at the whole picture. That whole picture should include the many services agriculture in our community provides which don’t show up as cash someone can take to the bank.

The whole picture should also include the role that food and local food production plays in building and strengthening the connections we have with each other in our community. Sharing food is an important part of connection and community, something recognized by many cultures and traditions, such as the Christian tradition I started this post with. Producing food within the boundaries of the city of Kelowna can contribute to our connection as a community. The more people in the community that can be involved with some aspect of food production, the more opportunities there are to build those connections. Providing the opportunities for people to be involved requires creative policy approaches that recognize the unique challenges posed by farming in the urban fringe, and that support agriculture in contributing all it can in the many ways it does to the health and well being of our community.

http://rustikmagazine.com/community-suppers-celebrate-your-sense-of-place/

So back to the question of why were some people so upset by what I wrote in my previous post? I’m sure each person has their own answer. When I listen to the many varied and sometimes contradictory reasons people have for supporting local food production, the link I see is between food and community. We live at a time where social connections don’t just happen. We can easily sit at home and have little connection with other people or the natural world. Local food production is a way for us to connect with our local environment, and a way to connect with others in our community. Those connections are fundamental to human health and well being, and keeping agriculture and food production as a part of the Kelowna landscape is an important part of protecting and enhancing our local quality of life. I think we lack an effective language to speak about these things, and so have come to rely on economic and environmental arguments as justifications. Therefore, challenging the environmental and economic justifications people have come up with threatens something much deeper than just those justifications. I’m sure that those who stand to gain by developing agricultural land are quite familiar with the facts that I described in my last post, and use them as part of their arguments in favour of development. I hope we can find a more convincing language to describe the importance of local food production than the easily refuted economic and environmental arguments. There is far more to the health and well being of the people of Kelowna than economic growth alone.

And most importantly, if you care about these issues and want to be heard, pay attention for opportunities to contribute to the updating of Kelowna’s agricultural plan.

Follow

Follow

To me, agriculture, and in particular fresh, juicy apricots and peaches define the Okanagan. Before buying a place and planting some of my own trees, I would keep visiting the BC Tree Fruits store in anticipation of the first apricots, buying a box as soon as I could, and polishing it off within a week, largely on my own, before going back for the next one. Once the peaches arrived, same story. These fruits are what make my summer. To me, this place would truly lack something special if that local season of soft fruits wasn’t part of our year.

To me, agriculture, and in particular fresh, juicy apricots and peaches define the Okanagan. Before buying a place and planting some of my own trees, I would keep visiting the BC Tree Fruits store in anticipation of the first apricots, buying a box as soon as I could, and polishing it off within a week, largely on my own, before going back for the next one. Once the peaches arrived, same story. These fruits are what make my summer. To me, this place would truly lack something special if that local season of soft fruits wasn’t part of our year. Fact #2: We don’t need local agriculture to feed ourselves. We do need agriculture to feed ourselves. Farmers feed the world. However, that doesn’t mean the farms need to be nearby, such as within the urban boundaries of Kelowna. Over the long term, food prices have been falling, even as global populations have been increasing. Yield per acre and yield per person have been increasing everywhere in the world. Malthus’ predictions that the ability to produce food will be what eventually limits population growth – famine if pestilence and disease are insufficient – seems so far to have been kept at bay. Loosing the food production that occurs in Kelowna would have little discernible impact on food prices or food availability in the city.

Fact #2: We don’t need local agriculture to feed ourselves. We do need agriculture to feed ourselves. Farmers feed the world. However, that doesn’t mean the farms need to be nearby, such as within the urban boundaries of Kelowna. Over the long term, food prices have been falling, even as global populations have been increasing. Yield per acre and yield per person have been increasing everywhere in the world. Malthus’ predictions that the ability to produce food will be what eventually limits population growth – famine if pestilence and disease are insufficient – seems so far to have been kept at bay. Loosing the food production that occurs in Kelowna would have little discernible impact on food prices or food availability in the city.

Culture and History: While agriculture may presently represent a small part of the Okanagan economy, it was instrumental to the settlement of the Okangan by immigrants who arrived during the last couple of centuries. Maintaining a working landscape provides a connection with that history and our cultural heritage. A related issue is the importance of protecting lands that provide traditional indigenous foods, but that is a discussion for another day.

Culture and History: While agriculture may presently represent a small part of the Okanagan economy, it was instrumental to the settlement of the Okangan by immigrants who arrived during the last couple of centuries. Maintaining a working landscape provides a connection with that history and our cultural heritage. A related issue is the importance of protecting lands that provide traditional indigenous foods, but that is a discussion for another day. Connection with the Seasons: When agriculture is part of our landscape, we are exposed to the natural cycles that farmers live with. Seeing spring blossoms, summer irrigation, fall harvest, and winter pruning provides us with a deeper connection with the place in which we live. This is particularly true when we as a community make a concerted effort to integrate these seasons into the events and activities hosted as a community.

Connection with the Seasons: When agriculture is part of our landscape, we are exposed to the natural cycles that farmers live with. Seeing spring blossoms, summer irrigation, fall harvest, and winter pruning provides us with a deeper connection with the place in which we live. This is particularly true when we as a community make a concerted effort to integrate these seasons into the events and activities hosted as a community.

As a general rule, I am quick to dismiss pretty much everything that has a supernatural

As a general rule, I am quick to dismiss pretty much everything that has a supernatural

I also wonder if hearing these stories and participating in these traditions, stories and traditions that emerged in the places we live, can be a valuable part of connecting us to this place. Those of us who are immigrants have brought with us our stories and traditions. Those may have been valuable in helping us to thrive in the places we came from. However, they may not be the best fit locally. Maybe if we heard these locally rooted stories ourselves, on a regular basis, maybe we would be more connected to where we live. Maybe then we would be emotionally tied to the health of our local ecosystems and be more willing to work to protect them. This is consistent with emerging research showing how fostering environmental empathy can lead to an increase in willingness to change behavior.

I also wonder if hearing these stories and participating in these traditions, stories and traditions that emerged in the places we live, can be a valuable part of connecting us to this place. Those of us who are immigrants have brought with us our stories and traditions. Those may have been valuable in helping us to thrive in the places we came from. However, they may not be the best fit locally. Maybe if we heard these locally rooted stories ourselves, on a regular basis, maybe we would be more connected to where we live. Maybe then we would be emotionally tied to the health of our local ecosystems and be more willing to work to protect them. This is consistent with emerging research showing how fostering environmental empathy can lead to an increase in willingness to change behavior. I have heard my colleague Jeannette Armstrong speak on a couple of occasions where she describes indigeneity being about connection to place, not about race. I am beginning to wonder if that connection needs to be founded in stories and traditions that are rooted in this place. The Peach Festival, the Wine Festival, etc. are great events that connect us with the landscape as we have modified it. However, they don’t connect us to the natural environment as it would exist. Maybe we need a festival around the blossoming of the arrow leaf balsam root and the saskatoon bush, natural heralds of the season here in the Okanagan. Maybe we need to hear stories about the salmon,the sagebrush, and the ponderosa. Maybe if we are more connected to these stories, we’ll feel a greater loss when these are lost, and we will be more willing to work to protect the natural Okanagan environment.

I have heard my colleague Jeannette Armstrong speak on a couple of occasions where she describes indigeneity being about connection to place, not about race. I am beginning to wonder if that connection needs to be founded in stories and traditions that are rooted in this place. The Peach Festival, the Wine Festival, etc. are great events that connect us with the landscape as we have modified it. However, they don’t connect us to the natural environment as it would exist. Maybe we need a festival around the blossoming of the arrow leaf balsam root and the saskatoon bush, natural heralds of the season here in the Okanagan. Maybe we need to hear stories about the salmon,the sagebrush, and the ponderosa. Maybe if we are more connected to these stories, we’ll feel a greater loss when these are lost, and we will be more willing to work to protect the natural Okanagan environment.

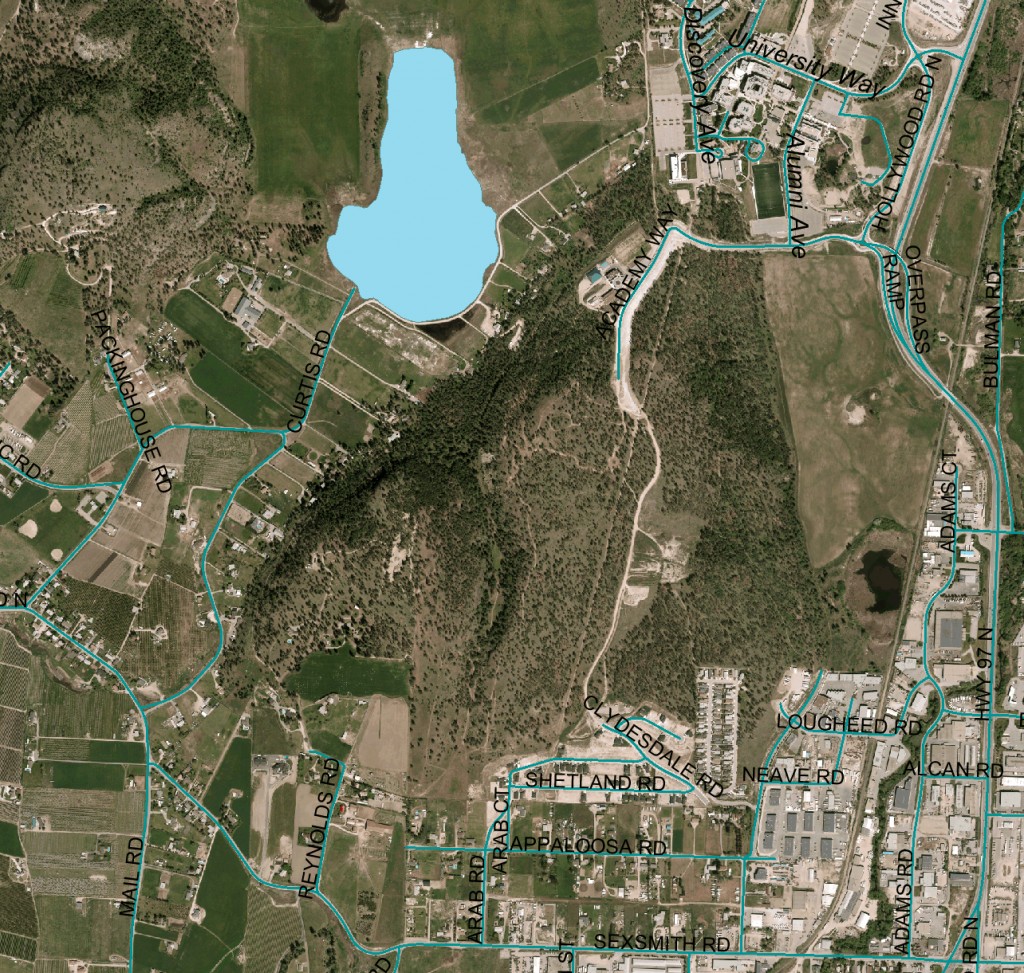

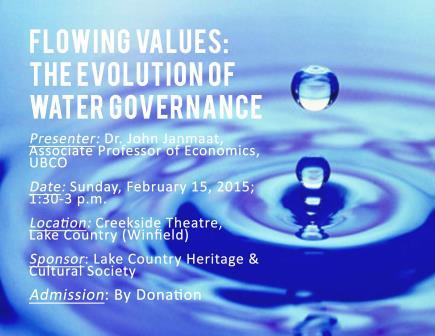

A doctoral student and I have a project underway right now that seeks to understand a bit more about the value people place on the goods and services provided by the environment here in the central Okanagan. Our project is based on a couple of key ideas. The first, it isn’t possible for people to have everything they want. The second is that the best way to understand the value people put on the environment is to ask them to choose the best balance between the different things that they might want. It isn’t my job to tell people what the right balance is between the environment and other goals. Rather, I have to listen to what people tell me the right balance is.

A doctoral student and I have a project underway right now that seeks to understand a bit more about the value people place on the goods and services provided by the environment here in the central Okanagan. Our project is based on a couple of key ideas. The first, it isn’t possible for people to have everything they want. The second is that the best way to understand the value people put on the environment is to ask them to choose the best balance between the different things that they might want. It isn’t my job to tell people what the right balance is between the environment and other goals. Rather, I have to listen to what people tell me the right balance is.