This is a long one!

An economist and her friend are walking down the street when the friend sees a twenty dollar bill on the sidewalk. “Look,” he says, “it’s a twenty dollar bill”. “Nonsense,” says the economist. “If that was a twenty dollar bill, someone would have picked it up by now.”

An economist and her friend are walking down the street when the friend sees a twenty dollar bill on the sidewalk. “Look,” he says, “it’s a twenty dollar bill”. “Nonsense,” says the economist. “If that was a twenty dollar bill, someone would have picked it up by now.”

Education and experience have both taught me to be very suspicious when anyone suggests that there is a lot of money to be had for little effort. Thus, when it was suggested that amalgamating the water utilities in Kelowna together would generate large savings, I found it hard to believe. My questions and speculative answers were all ways that to me suggested the savings would be far less than advertised, and that something of value might be lost in the quest to achieve these savings. There are typically good reasons why those savings, that twenty dollar bill, have not already been picked up.

Recently, Alan Newcombe

Recently, Alan Newcombe

Divisional Director, Infrastructure with the City of Kelowna provided a great response to my previous blog post on the “Five or One” question. You can read it by scrolling to the end of my previous post. The overarching argument seems to be that from the perspective of those speaking on behalf of the city, the best governance model for the city includes all services such as water being under the authority of the city. The assertion is made that among the benefits of bringing all water supply under the control of the city will be substantial cost savings. The governance question is a big question that is about far more than the cost of service delivery, and in my opinion decisions about governance should not revolve strictly around the cost question. Having said that, I do think there is merit in examining critically some of the claims about the cost savings that can be had.

A point by point discussion of which cost savings are likely to be realized and which not will, I believe, prolong the argument and divert attention from the governance issue. I put forward a number of questions in my previous post and suggested that in response to those questions, which were areas where one might expect cost savings, that I didn’t think the actual savings would be that large. How large the savings will be depends on how amalgamation is accomplished, and unfortunately whatever choice we make, we will never know whether we actually saved money relative to the other option.  Even the time traveling T.A.R.D.I.S. of Dr. Who would not be enough, as we would need a parallel universe where the only thing different is that in one universe the system was amalgamated and in the other it was not. To date, we have neither perfected time travel nor travel between multiple dimensions, in spite of its common theme in science fiction. Since we cannot know what the costs will be with and without amalgamation, our best indication of the effects of an amalgamation would be to carefully examine the costs of different sized utilities. Such examinations have been done.

Even the time traveling T.A.R.D.I.S. of Dr. Who would not be enough, as we would need a parallel universe where the only thing different is that in one universe the system was amalgamated and in the other it was not. To date, we have neither perfected time travel nor travel between multiple dimensions, in spite of its common theme in science fiction. Since we cannot know what the costs will be with and without amalgamation, our best indication of the effects of an amalgamation would be to carefully examine the costs of different sized utilities. Such examinations have been done.

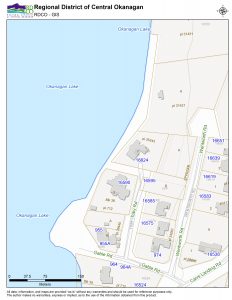

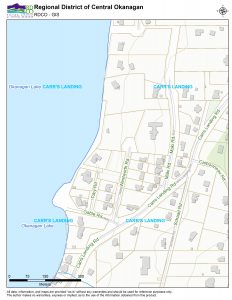

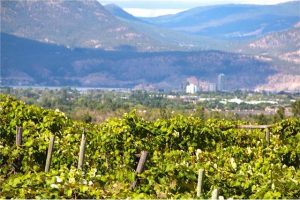

In a recent doctoral thesis, Hugh Boyd Wenban-Smith (2009) carefully separates the cost structure of a set of water utilities in the UK and in the USA between treatment and distribution. He finds the result that many others have found for treatment, namely that there are significant economies of scale. Larger water utilities have lower costs per unit of water treated. However, whether there is an overall cost advantage to larger utilities comes down to the form of the community and the resultant distribution costs. Communities that are densely built have distribution costs that decrease with community size as well as decreasing treatment costs. However, for sprawling communities and communities that are made up of settlements spread across the landscape, distribution costs are increasing in community size. Kelowna has a combination of sprawling, low density development together with dispersed settlement pockets (Gallagher’s Canyon, Sunset Ranch, …). This means that if amalgamation is accomplished by replacing the existing collection of water systems with one water system that covers the entire city fed by centralized water treatment, the cost of that system is likely to be higher than what we have now.

Kelowna’s population is spread over a large area and a large elevation range. Analysis of a collection of water utilities that are mostly in areas with little variation in elevation may not capture all the issues important for Kelowna. Two recent papers, one looking at German water utilities (Zschille and Walter, 2010) and a second studying Swiss water utilities (Faust and Baranzini, 2014) are somewhat more representative of our geographic situation. Both find that increasing the elevation range over which water must be moved increases the cost of the utility. In other words, in Kelowna, the large elevation range will increase the adverse cost impact of an amalgamated utility, if that utility is going to centralize treatment using the lake as a source.

The importance of urban form in the cost of providing services like water cannot be overemphasized. It has long been recognized that sprawling low density development is costly to service. Sprawling low density development that spreads high up our hillsides is even more costly. Redoubling efforts to encourage infill development and increasing density within the existing built areas of the city will increase the cost effectiveness of water supply and of other urban infrastructure. The city’s efforts in this area should be applauded.

Faust and Baranzini (2014) also find that areas with more extremes in weather (especially periods of drought) tend to have higher water utility costs. This isn’t surprising, as in such areas the water utilities will need to maintain capacity for these extreme times. Kelowna is rightly proud of the fact that for a decade it has accommodated population growth without increasing total water demand. Higher density, successful efforts to reduce outdoor water use, metering and pricing by volume, etc. have meant that expensive capacity expansion could be delayed. However, the irrigation districts were built to supply water for irrigation, and being able to meet the needs of irrigators during times of drought was the reason these systems were built to the capacity they have. While there is certainly scope for ongoing improvements in efficiency on the farm, farmers livelihoods will continue to depend on supplying their crops with enough water.

Finally, work by Destandau and Garcia (2014) looks at quality of service as a dimension of water supply activities. In essence, water utilities are not just providing water, but they are providing services as well. Increasing the size of water utilities is generally accompanied by a reduction in the quality of service. Put another way, if the water utilities in Kelowna are absorbed by the city, and if the city is committed to maintaining the same quality of service that people presently enjoy, the cost savings from amalgamation will be smaller (or the cost of amalgamation larger). The staff that appear redundant from a strict accounting perspective are in fact providing a service that the people served value.

Overall then, the evidence from other jurisdictions is that whether or not a single large water utility will have lower costs than our current system of five relatively large utilities (and 27 tiny ones, more on that later) is uncertain. We have some of the factors that tend to increase costs for a larger entity, namely dispersed settlement pockets, sprawl, and large elevation ranges. Water drawn from the lake can presently be treated at lower cost than that collected from the uplands, thanks to an ongoing filtration deferral that the city has. However, water collected from the uplands can be moved by gravity, rather than needing to be pumped. There are also costs associated with amalgamation, and those who have renovated a home know it often isn’t clear whether the cost of the renovation will ever be paid back in terms of a higher home value or savings on things like heating costs. You do the renovation because you expect to be happier in the home after the renovation than the one you currently live in. In the end then, I am still left skeptical about the cost savings that bringing water supply services under the control of the city will bring. Or to put it another way, I don’t think the financial argument is the winning argument to justify amalgamation.

From my perspective, the ‘citizens’ of our city are far more than just rate payers, and even if there were a clear financial advantage to amalgamation, that would on its own not be justification. There are other values that factor in, and the question is how do we balance these values and arrive at the best choice. In situations like this, there is no right answer. Solving such ‘wicked problems’ really involves finding solutions that balance the conflicting values in such a way that everyone is willing to ‘give it a try’. What doesn’t work is when one party decides its values, its vision, is the right one and attempts to force it on all the others. A willingness to listen, to truly appreciate the perspectives of the others, and to take the time necessary to bring everyone on board, are critical to finding solutions to such problems.

Mr. Newcomb makes reference to the provincial policy on improvement districts. The policy is to have the improvement districts all eventually absorbed into municipalities or regional districts, except in those rare cases where there is no alternative. It is pointed out that some improvement districts, particularly the smaller ones, are challenged to provide the effective governance that is felt appropriate for an entity providing a public service. The assertion is that the public is best served by having only one level of local government which is responsible for land use planning and the services that are needed to support the various land uses. This assertion reflects a particular perspective on the purpose of local government and the best governance model to achieve that purpose. Whether or not this view on governance is ‘right’, the eventual dissolution of improvement districts is government policy.

Some excerpts from the government policy document highlight important aspects of the provincial perspective. First, as part of a list of governance issues, the document states:

relationships between improvement districts and regional districts: It is inevitable that there is potential for conflict when land use planning and servicing responsibilities are vested in different jurisdictions in rural areas;

The overall objective of the ministry is stated as:

The ministry expects that improvement districts will, over time, be converted to municipal or regional district jurisdiction and at some point in time all improvement districts will be under municipal or regional district jurisdiction. However, it is recognized that improvement districts will have an important role to play in providing local services to rural areas for some time and the process of change will largely be voluntary.

and in reference to changes to Bill 14 (Local Government Statutes Amendment Act, 2000):

At the same time, Bill 14 advances a number of changes to regional district legislation which will indirectly contribute to the vision and the objectives. These are:

- strengthening provisions for regional districts to establish elected local community commissions to manage local services;

- enhancing flexibility for regional districts to establish management committees and commissions to oversee local services including those provided by former improvement districts; and

- requiring regional districts to consider whether consultation is required with improvement districts in preparing and amending official community plans.

So while the provincial policy does eventually see the assumption of the responsibilities of improvement districts by regional districts or municipalities, this is not something that the province intends to force, and the legislation enables the creation of entities to manage the delivery of local services. It would seem that from the provinces perspective, acquisition of the irrigation districts by the city is not the only solution.

There are likely a number of governance related issues that need to be sorted out before the water utilities serving Kelowna can be effectively absorbed into either the city or regional district. That the five main water utilities were talking about these issues when they developed the integration plan is certainly a good start. This conversation needs to continue with all the parties committed to working together, and being open to a solution emerging from those discussions.

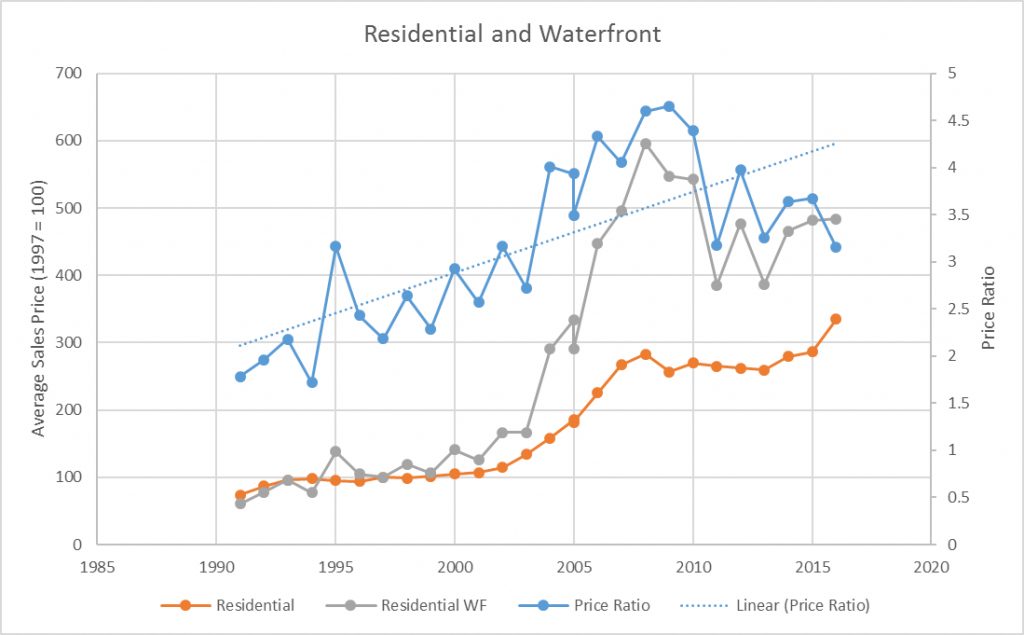

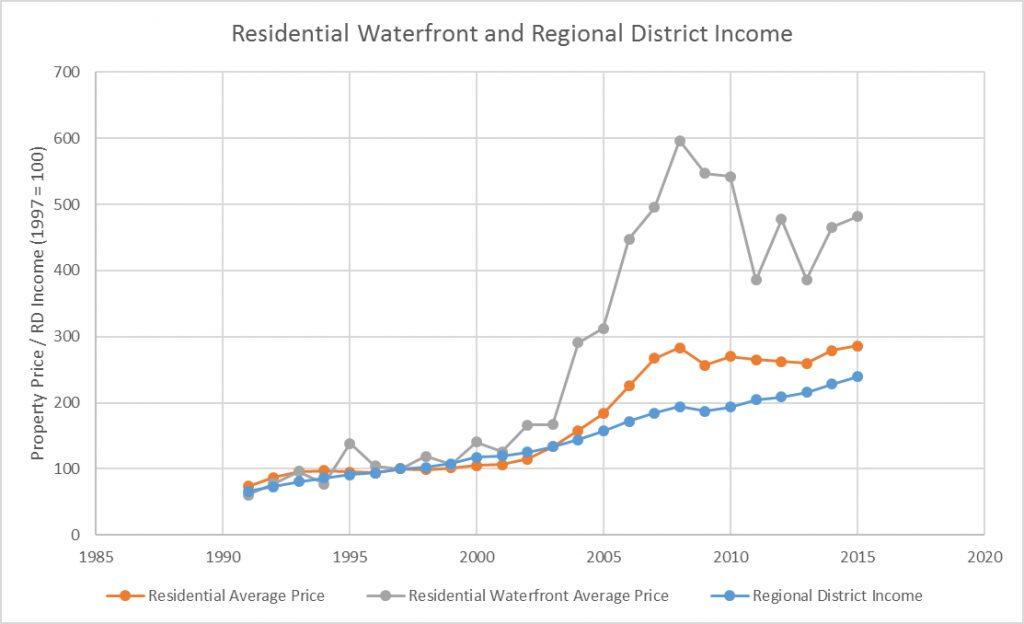

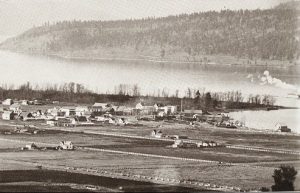

The irrigation districts, to varying degrees, supply a substantial share, if not a majority, of their water to irrigators. To the extent that the interests of the city and that of the irrigation community do not align, there is the potential for conflict. From a governance perspective, one key question is whether the interests of the irrigation community will be fairly accommodated within one Kelowna water utility. I have pointed out elsewhere (Kelowna’s Agriculture Plan) that agriculture makes up a very small share of the local economy. However, it uses a large share of the water. The largest driver of Kelowna’s economy is immigration, and the construction and other activities (i.e. real estate, legal services, etc.) that need to take place to accommodate that immigration. A tremendous amount of wealth has been created for those in Kelowna who have land and been able to provide it for development. When there is a boom in housing demand, such as has been occurring recently, there is much potential wealth to be generated for land owners who can develop their land. As Mark Twain said “buy land, they aren’t making any more of it”.

Kelowna’s city council is keenly aware that when immigration slows and construction slows, the city economy suffers far more than the impact of changes in apple prices or the occurrence of a late spring frost. Beyond land owners, many residents of Kelowna are employed in industries that rely on this continuing growth, and they suffer when growth slows. These are voters and residents, and council rightly should be attune to their situation. Counselors are in a challenging position, trying to make decisions that strike the right balance among the varied values that Kelowna residents care about, while facing constant pressure from various interests seeking to promote their own needs. There are more than 100,000 residents who drink water in Kelowna, while a few thousands are substantially impacted by what happens in agriculture. Agriculture accounts for perhaps half or more of all the water that is used. In such a situation, it may make sense for the agricultural community to have some level of control or ownership over their access to water, lest their interests be lost among the many conflicting demands on city government. Alan’s comments include seeing the need for “A plan that protects agriculture …” I’m glad that the city recognizes this. However, there is a fundamental difference between the city having the responsibility to protect the interests of agriculture and agriculture having the power and tools to protect its own interests.

The bottom line is that the agricultural community needs to have some level of real power when it comes to decisions about water, decisions that can affect their livelihoods. That is a critical governance challenge, and I do not think it should be constrained by an imposed deadline for amalgamation. An imposed deadline with the end result being that the city assumes responsibility for all water means that the city does not have to meaningfully engage with the affected parties on the needs of agriculture or on any other issue. They can just wait until the deadline arrives, and then have things their way.

The agricultural community has long taken issue with having to pay the cost of treating water to potable quality when the majority of that water is used for irrigation. The differential rates between residential and agricultural users reflect this, but this difference in rates is also something of an uneasy peace where people avoid talking about the issue. Is there a way to reshape the governance of water in Kelowna such that irrigation and residential supply are separated?

There are few jurisdictions outside of British Columbia where irrigation districts are as active in the supply of domestic water as they are here. I am no expert on the history of this, but at the very least the residential development that the irrigation districts ended up supplying were approved by some other level of government, the level that had authority over zoning (city, regional district or province as the case may be). In most other jurisdictions, the equivalent of our irrigation districts supply only irrigation water, and they may be bulk water suppliers to other utilities that take responsibility for supplying drinking water. Is there anything we can learn from this?

Could we separate responsibility for irrigation and drinking water supply. The city could take on all responsibility for supplying potable water to all residents of Kelowna. The irrigation districts would then only be responsible for supplying irrigation water that is treated to a level that meets the needs of agriculture. All non-agricultural residents throughout the city would then pay one water bill to the city, and the city would be responsible for figuring out how to best supply potable water to those residents, where ever they are in the city, and how to fairly charge residents, based on where they are and the cost of delivering potable water to them. Agricultural residents would pay two bills, one to the city for their drinking water, and a second to their irrigation district for their irrigation water.

Such an arrangement would leave the city free to determine the best way to supply potable water to all Kelowna residents, and relieve the irrigation districts of the responsibility of figuring out how to supply potable water through a system that is primarily designed to supply irrigation water. For some neighbourhoods, the best solution may be for the city to twin lines and connect to the current city system. In other places the city may opt to pay for twinning lines and installing a small treatment plant, supplying it from a well or purchasing the water from an irrigation district. For some residences, it may be most cost effective for the city to install point of entry treatment systems that treat the water for one house alone. Figuring out how to pay for these system upgrades would then fall to the city, taking the issue away from the irrigation districts and the challenges they have had raising money. I don’t know if such an option has been seriously considered, and I would not be surprised if there are things about this suggestion I have not recognized.

Finally, there is the question of drinking water quality among the 27 other very small utilities within the boundaries of Kelowna. The public debate doesn’t seem to have touched on these much. For these small utilities, many of which can be connected to the city system or one of the larger irrigation districts for relatively minimal cost, amalgamation makes sense. In my opinion, the other governance issues loom less large here, and the threats to people’s health are likely larger. There is of course the question of who will pay, but so long as there is good faith negotiation on the part of all involved, such things can be resolved.

I do not see any reason to rush forward with amalgamation. There are some serious governance issues that need to be sorted out, particularly ensuring that the agricultural community has a real say (i.e. has real power) about how water is managed. I think we are facing conflicting visions about what a city should be and do. The economics of service delivery are not conclusive, and even if they were, there are other values, some related to the final outcome and others to the process of getting there, that are also involved. I do not see any obviously right answer, beyond moving forward with those investments in the system that make sense, whatever the future relationship is between the water providers. Solving dilemmas such as this requires communication, a willingness to listen and appreciate others perspectives, and patience. The best solutions are not found in a hurry.

References

Destandau, François and Serge Garcia (2014). Service quality, scale economies and ownership: an econometric analysis of water supply costs. Journal of Regulatory Economics 46(2): 152-182

Faust, Anne-Kathrin and Andrea Baranzini (2014). The economic performance of Swiss drinking water utilities. Journal of Production Analysis 41:383-397.

Wenban-Smith, Hugh B. (2009) Economies of scale, distribution costs and density effects in urban water supply: a spatial analysis of the role of infrastructure in urban agglomeration. PhD thesis, The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE).

Zschille, Michael and Matthias Walter (2010). Cost Efficiency and Economies of Scale and Density in German Water Distribution. German Institute for Economic Research (DIW), Berlin, Germany.

The economist David Ricardo (1772-1823) is credited with the Law of Rent. Ricardo observed that the maximum a tenant would pay to rent a parcel of land depended on what they could earn by renting the land, relative to renting another parcel. It does not depend on what they actually earn by renting the land. If there are no limits on what an owner or tenant can use their land for, then it will (eventually) be put to that use which results in the highest earnings. That use will depend on the options available, options that depend on restrictions like zoning, OCPs, environmental requirements, the Agricultural Land Reserve, etc.

The economist David Ricardo (1772-1823) is credited with the Law of Rent. Ricardo observed that the maximum a tenant would pay to rent a parcel of land depended on what they could earn by renting the land, relative to renting another parcel. It does not depend on what they actually earn by renting the land. If there are no limits on what an owner or tenant can use their land for, then it will (eventually) be put to that use which results in the highest earnings. That use will depend on the options available, options that depend on restrictions like zoning, OCPs, environmental requirements, the Agricultural Land Reserve, etc.

What is the difference between a natural resource like zinc and land? Zinc is a finite, nonrenewable resource whose value depends on global markets. The demand in those markets is based on technologies that use zinc, and has nothing to do with how much zinc there is in the world. The price does depend on how much there is, and the profits that owners of zinc deposits earn depends on that price. Land in Kelowna is a finite, nonrenewable resource whose value depends on global markets. The demand in those markets is based on income levels and preferences for the natural and human created amenities in the area, and has nothing to do with how much land there is in Kelowna. However, the price does, and the profits that land owners can earn depends on that price. Like zinc, land owners do not create the value of their location. They may add value by developing something on the land, but the value of the bare land is a consequence of a larger market. Should we be collecting royalties on land development in the same way we do on natural resources?

What is the difference between a natural resource like zinc and land? Zinc is a finite, nonrenewable resource whose value depends on global markets. The demand in those markets is based on technologies that use zinc, and has nothing to do with how much zinc there is in the world. The price does depend on how much there is, and the profits that owners of zinc deposits earn depends on that price. Land in Kelowna is a finite, nonrenewable resource whose value depends on global markets. The demand in those markets is based on income levels and preferences for the natural and human created amenities in the area, and has nothing to do with how much land there is in Kelowna. However, the price does, and the profits that land owners can earn depends on that price. Like zinc, land owners do not create the value of their location. They may add value by developing something on the land, but the value of the bare land is a consequence of a larger market. Should we be collecting royalties on land development in the same way we do on natural resources?

While indigenous perspectives do not seem to see any land as unused, the colonizing perspective in North America and elsewhere that western society has expanded into proceeded for a long time by granting vacant land to settlers. We have largely run out of vacant (stolen?) land to hand out to people without land. Until we start colonizing other worlds, we are going to have to figure out how to manage the development of land in a way that balances the rights of land owners with the fundamental human need for housing, the community need for public amenities, and the needs of the environment (of the land) we all live within. Do we have that balance right?

While indigenous perspectives do not seem to see any land as unused, the colonizing perspective in North America and elsewhere that western society has expanded into proceeded for a long time by granting vacant land to settlers. We have largely run out of vacant (stolen?) land to hand out to people without land. Until we start colonizing other worlds, we are going to have to figure out how to manage the development of land in a way that balances the rights of land owners with the fundamental human need for housing, the community need for public amenities, and the needs of the environment (of the land) we all live within. Do we have that balance right?

Follow

Follow

The damage to docks in particular has been recognized as an opportunity by some, including our mayor and a few counselors, to look for stronger enforcement of regulations concerning structures on the foreshore. With appropriate permitting, waterfront property owners can install docks. They cannot build other structures on the foreshore. A properly constructed dock will be built to allow passage, either beginning below the high water mark, or incorporating stairs or some other means for the public to pass the dock. Many docks are not built this way. Now that many have to be repaired or rebuilt, it does create an opportunity for inspections to take place and action taken to ensure compliance, so that those who cannot afford to own waterfront property have the opportunity to enjoy the lake that they legally have the right to enjoy.

The damage to docks in particular has been recognized as an opportunity by some, including our mayor and a few counselors, to look for stronger enforcement of regulations concerning structures on the foreshore. With appropriate permitting, waterfront property owners can install docks. They cannot build other structures on the foreshore. A properly constructed dock will be built to allow passage, either beginning below the high water mark, or incorporating stairs or some other means for the public to pass the dock. Many docks are not built this way. Now that many have to be repaired or rebuilt, it does create an opportunity for inspections to take place and action taken to ensure compliance, so that those who cannot afford to own waterfront property have the opportunity to enjoy the lake that they legally have the right to enjoy.

A few researchers have come up with estimates of the value of a visit to the beach. Chen (2013) used the travel behavior of Michigan residents to estimate the value of the beaches on Lake Michigan. Since people won’t make the trip unless the value they gain from visiting the beach exceeds the cost, the cost of the trip gives a minimum value for the experience. Chen found that the value was between $32 and $39 per person in 2011 dollars. For the Italian resort town of Lido di Dante, Brandolini estimates a value of 26 to 27 Euro per day visit. Lew and Larson (2008) use the value of people’s time to estimate what a beach visit is worth for San Diego county, finding values in the range of $21 to $23 per day. Penn et al (2016) use a survey approach, where people are asked to choose between different beach configurations. Locals put a greater value on beaches that were less crowded, while tourists would pay more to ensure high water quality. Or, for Kelowna, in the middle of the summer when the beaches are crowded, many locals may just stay home.

A few researchers have come up with estimates of the value of a visit to the beach. Chen (2013) used the travel behavior of Michigan residents to estimate the value of the beaches on Lake Michigan. Since people won’t make the trip unless the value they gain from visiting the beach exceeds the cost, the cost of the trip gives a minimum value for the experience. Chen found that the value was between $32 and $39 per person in 2011 dollars. For the Italian resort town of Lido di Dante, Brandolini estimates a value of 26 to 27 Euro per day visit. Lew and Larson (2008) use the value of people’s time to estimate what a beach visit is worth for San Diego county, finding values in the range of $21 to $23 per day. Penn et al (2016) use a survey approach, where people are asked to choose between different beach configurations. Locals put a greater value on beaches that were less crowded, while tourists would pay more to ensure high water quality. Or, for Kelowna, in the middle of the summer when the beaches are crowded, many locals may just stay home. An economist and her friend are walking down the street when the friend sees a twenty dollar bill on the sidewalk. “Look,” he says, “it’s a twenty dollar bill”. “Nonsense,” says the economist. “If that was a twenty dollar bill, someone would have picked it up by now.”

An economist and her friend are walking down the street when the friend sees a twenty dollar bill on the sidewalk. “Look,” he says, “it’s a twenty dollar bill”. “Nonsense,” says the economist. “If that was a twenty dollar bill, someone would have picked it up by now.” Recently, Alan Newcombe

Recently, Alan Newcombe Even the time traveling T.A.R.D.I.S. of Dr. Who would not be enough, as we would need a parallel universe where the only thing different is that in one universe the system was amalgamated and in the other it was not. To date, we have neither perfected time travel nor travel between multiple dimensions, in spite of its common theme in science fiction. Since we cannot know what the costs will be with and without amalgamation, our best indication of the effects of an amalgamation would be to carefully examine the costs of different sized utilities. Such examinations have been done.

Even the time traveling T.A.R.D.I.S. of Dr. Who would not be enough, as we would need a parallel universe where the only thing different is that in one universe the system was amalgamated and in the other it was not. To date, we have neither perfected time travel nor travel between multiple dimensions, in spite of its common theme in science fiction. Since we cannot know what the costs will be with and without amalgamation, our best indication of the effects of an amalgamation would be to carefully examine the costs of different sized utilities. Such examinations have been done.

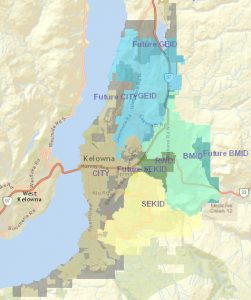

The managers of all these water utilities are planning infrastructure upgrades and expansions to deal with their respective challenges. They recognize that there is scope to support each other, and cooperate through the

The managers of all these water utilities are planning infrastructure upgrades and expansions to deal with their respective challenges. They recognize that there is scope to support each other, and cooperate through the

multiple sources we have. There may be some neighbourhoods around the edges where it would make sense to switch from one provider to another. However, for the bulk of Kelowna residents, my guess is that the system in place right now is probably not far from the lowest cost system, and given that it is in place and largely working, replacing it with something ‘fresh of the drawing board’ would be an expensive way of getting something that is only slightly better than what we’ve got. Therefore, it would seem that any difficulties in cooperation between the water providers are not preventing us from realizing large savings on the physical infrastructure we need to deliver water in Kelowna.

multiple sources we have. There may be some neighbourhoods around the edges where it would make sense to switch from one provider to another. However, for the bulk of Kelowna residents, my guess is that the system in place right now is probably not far from the lowest cost system, and given that it is in place and largely working, replacing it with something ‘fresh of the drawing board’ would be an expensive way of getting something that is only slightly better than what we’ve got. Therefore, it would seem that any difficulties in cooperation between the water providers are not preventing us from realizing large savings on the physical infrastructure we need to deliver water in Kelowna. Agriculture adds a level of complexity to this situation. Irrigators use a large share of the delivered water in Kelowna, for example in the neighbourhood of three quarters of the water SEKID delivers. However, there are relatively few farmers in Kelowna, and agriculture makes up a relatively small share of the city economy. Water utility trustees, even if not farmers, are probably more likely to pay attention to farmers’ concerns than city council. Water utility trustees are not responsible for zoning decisions, sports and recreation, roads and transportation, etc. They are responsible only for overseeing their water utility, more likely to pay attention to water issues, and therefore more likely to listen to farmers.

Agriculture adds a level of complexity to this situation. Irrigators use a large share of the delivered water in Kelowna, for example in the neighbourhood of three quarters of the water SEKID delivers. However, there are relatively few farmers in Kelowna, and agriculture makes up a relatively small share of the city economy. Water utility trustees, even if not farmers, are probably more likely to pay attention to farmers’ concerns than city council. Water utility trustees are not responsible for zoning decisions, sports and recreation, roads and transportation, etc. They are responsible only for overseeing their water utility, more likely to pay attention to water issues, and therefore more likely to listen to farmers. It is pretty obvious that food security is a term that can get some people pretty excited, particularly when they see it as under threat. However, when I listen to what people are saying, I’m left with the impression that people have a range of different definitions for the term ‘food security’. As a result, we may be talking past each other, rather than with each other, which really doesn’t do much for building consensus. So, I’m going to do what academics do well, which is pick one clear definition and work through the relationship of that definition to the role of agriculture in Kelowna.

It is pretty obvious that food security is a term that can get some people pretty excited, particularly when they see it as under threat. However, when I listen to what people are saying, I’m left with the impression that people have a range of different definitions for the term ‘food security’. As a result, we may be talking past each other, rather than with each other, which really doesn’t do much for building consensus. So, I’m going to do what academics do well, which is pick one clear definition and work through the relationship of that definition to the role of agriculture in Kelowna. Within this definition, people have come to recognize four ‘pillars’: availability, access, utilization and stability. The definition does not mention local food production. If local food production is central to your definition of food security, then you won’t like this definition. If I am good with this definition and you are not, until we straighten out a common language, it will be very hard for us to get anywhere. Perhaps the way forward is to let go of the term ‘food security’, and focus on the identified pillars directly. The question then is whether or not local food production, particularly within the boundaries of the city of Kelowna, contributes to these pillars.

Within this definition, people have come to recognize four ‘pillars’: availability, access, utilization and stability. The definition does not mention local food production. If local food production is central to your definition of food security, then you won’t like this definition. If I am good with this definition and you are not, until we straighten out a common language, it will be very hard for us to get anywhere. Perhaps the way forward is to let go of the term ‘food security’, and focus on the identified pillars directly. The question then is whether or not local food production, particularly within the boundaries of the city of Kelowna, contributes to these pillars. Access. Some people talk about ‘food deserts’ (e.g.

Access. Some people talk about ‘food deserts’ (e.g.  Utilization. This is about how the food supply translates into the nutritional status of the person. Are people able to make wise choices in the preparation of what they eat and what they choose to eat, so that they are healthy. On its own, local food production has no connection to utilization. However, if local food producers help educate people who are not making the best choices for their health, then it can make a difference. Do efforts to enable the needy in our community to make healthful choices depend on food being produced in our community. They don’t. However, locally produced food can address utilization issues if it is linked to helping people make healthful choices.

Utilization. This is about how the food supply translates into the nutritional status of the person. Are people able to make wise choices in the preparation of what they eat and what they choose to eat, so that they are healthy. On its own, local food production has no connection to utilization. However, if local food producers help educate people who are not making the best choices for their health, then it can make a difference. Do efforts to enable the needy in our community to make healthful choices depend on food being produced in our community. They don’t. However, locally produced food can address utilization issues if it is linked to helping people make healthful choices. One way to think about how much we should pay is to think about the risks of our imported food supplies being interrupted or becoming suddenly much more expensive. There are lots of risks that people point out. Some fear that our global food system, which is perceived to rely on extensive monocultures, is vulnerable to pest and/or disease outbreaks that can rapidly devastate the global food supply. Some say we need to be ready in case of international conflict that interrupts supply chains. Some suggest that our modern trade treaties could collapse and trade wars ensue, making it much more difficult to import food from other countries. Some contend that our industrial food system is essentially mining the land, and that at some point it will collapse, and we need local, small scale, ecological agriculture to feed ourselves when this happens. Some argue that climate change will make some parts of the world unsuitable for growing food, and we need to protect all the productive areas we have now, to make up for this coming loss. These are some of the arguments I have heard, and I expect there are even more.

One way to think about how much we should pay is to think about the risks of our imported food supplies being interrupted or becoming suddenly much more expensive. There are lots of risks that people point out. Some fear that our global food system, which is perceived to rely on extensive monocultures, is vulnerable to pest and/or disease outbreaks that can rapidly devastate the global food supply. Some say we need to be ready in case of international conflict that interrupts supply chains. Some suggest that our modern trade treaties could collapse and trade wars ensue, making it much more difficult to import food from other countries. Some contend that our industrial food system is essentially mining the land, and that at some point it will collapse, and we need local, small scale, ecological agriculture to feed ourselves when this happens. Some argue that climate change will make some parts of the world unsuitable for growing food, and we need to protect all the productive areas we have now, to make up for this coming loss. These are some of the arguments I have heard, and I expect there are even more.

Should Kelowna’s revised agricultural plan speak to local food production as a means of addressing food security challenges in our community? Should we as a community be developing policy that takes the potential for local food production to address community food security issues and makes it a reality? The plan is being revised, and there are opportunities to contribute. If you care about these issues, you can visit the website, complete the survey, and/or attend a public event where input is sought.

Should Kelowna’s revised agricultural plan speak to local food production as a means of addressing food security challenges in our community? Should we as a community be developing policy that takes the potential for local food production to address community food security issues and makes it a reality? The plan is being revised, and there are opportunities to contribute. If you care about these issues, you can visit the website, complete the survey, and/or attend a public event where input is sought.