Comments on the Regulations on the Principal Officials in Charge of the Party and the Government to Fulfill the Responsibility to Promote Rule of Law

Written by: Jiang Wan, translated by Yan Wang

Posted On: July 21, 2020

(The following is a translation of a shorten version of Professor Wan’s longer blog entry in Chinese.)

In December 2016, the General Office of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the General Office of the State Council jointly issued the Regulations on the Principal Officials in Charge of the Party and the Government to Fulfill the Responsibility to Promote Rule of Law (hereinafter referred to as the Regulations). The Regulations set out the main responsibilities of the principal officials in charge of the party committee and the government in promoting rule of law, and require that the principal officials should include their performance in promoting rule of law in their year-end reports. The higher-level party committee should consider lower officials’ performance during evaluation. If a principal official fails to fulfill their duties, they shall be held accountable in accordance with the relevant Party regulations such as the CCP Accountability Regulations, as well as national laws and regulations.

Performance evaluation and administration by law are generally considered distinctive governance methods. Rule of law is a profound revolution in China’s national governance. Why did the central leadership promote rule of law through performance evaluation?

I. Inherent discrepancy between performance evaluation and rule of law

For a long time, the central leadership has mainly used promotion as an incentive for local party and government leaders. It has also imposed constraints on local leaders through position adjustments. These personnel approaches served as a strong incentive and supervision mechanism for local party and government leaders. In order to get the promotion that they want, local leaders have no choice but to actively implement the policies issued the central leadership. Although performance evaluation can solve some problems in the principal-agent relationship between central and local leaderships, it may still fail to function as intended or to reflect the real situation. This is because local leaderships have the full control over their governance capabilities, governance behaviors and feedbacks on its performances. It is possible that local leaderships may conceal, exaggerate, or distort information. Moreover, overusing the mechanism of performance evaluation would lead to an emphasis on results rather than procedures, as well as a governance logic centered around evaluation.

When the central leadership cannot effectively control local leaderships through its personnel approaches, it is increasingly important to administer the local governments and control the behaviors of local leaderships by law. Contrary to performance evaluation, which focuses on results but neglects procedures, the primary function of regulating local leaderships by law is to ensure that the governance procedures themselves are regulated and legal, and to make sure that local governments are under an institutionalized supervision mechanism. The goal is to ensure smooth pass down of government orders and to maintain the authority of the central leadership. Moreover, administration by law can also provide fundamental insurance that the administrative bodies and their officials would truly serve the people’s interests, which will consequently consolidate the Party’s ruling position and realize long-term stability in the country.

Promoting administration by law can ensure that administrative procedures are regulated and in accordance to the law, but regulated procedures alone may not guarantee effectiveness. Not violating the law is only a minimum requirement. It does not reflect the ability or level of governance of local leaderships. In addition, China is still in the process of economic, social and political transformation, and policies rather than laws actually play a more important role within the government. For areas such as energy conservation, emission reduction, prevention of overcapacity, and real estate regulations, the legal basis for the implementation of policies is still extremely abstract, or even absent, and it is simply not feasible to control local leaderships by holding the local leaders legally accountable. In addition, China’s current political system has its distinctive characteristics. For example, each level of leadership is accountable only to the next level above, and the party committees of various levels have the leading power over the government bodies of the same levels. Although local party committees play a decisive role in local development, they usually do not replace local governments and do not directly perform administrative tasks. It is not feasible to control local party committees by holding them legally accountable.

II. Promoting rule of law through performance evaluation

The substance of promoting rule of law in governance is to regulate local administrative actions and to check arbitrary exercise of power. It will inevitably receive passive resistance from the local governments. In order to promote administration by law, the State Council issued the Outline for Comprehensively Promoting Administration by Law in 2004. The outline proposed that the executive heads of various local governments and departments are the primary responsible persons for the promotion of administration by law. In 2005, the State Council began to propose evaluations on the administration of local governments by law. In 2008, the Decision by the State Council on Strengthening Rule of Law in the Administration of the City and County Governments clearly put forward the requirement to establish a system for evaluating administration by law. The system listed several evaluation items: whether decisions are made in accordance with the law, whether regulatory documents are issued in accordance with the law, whether administrative management are implemented in accordance with the law, whether administrative review cases are accepted and dealt with in accordance with the law, and whether administrative responsibilities are performed in accordance with the law. These evaluation items are included in the performance evaluation of city and county governments and their officials. The evaluation results will affect rewards and penalties, as well as appointments, removals and promotions of officials. The decision also proposed that the principal persons in charge of the city and county governments should effectively assume the responsibilities of the primary person responsible for administration of governments by law. In 2010, the State Council’s Opinions on Strengthening the Construction of the Government under Rule of Law further proposed the establishment of a law-based administrative leadership coordination mechanism led by the principal leaders of various administrative agencies, where the evaluation results will serve as an important part of the comprehensive assessment of the government leaderships.

The Fourth Plenary Session of the 18th CCP Central Committee further stated that it is necessary to “take the implementation of rule of law as an important item in evaluating the actual performance of the leaderships at all levels, and incorporate it into the performance evaluation system.” It also proposed that the principal official in charge of the party and government should perform the duties of the primary person responsible for promoting rule of law. In December 2015, the CCP Central Committee and the State Council jointly issued the Outline for Promoting Rule of Law in the Administration of Governments (2015-2020), which expressly required that the principal officials of the party and the government shall perform the duties of the primary responsible person for promoting rule of law.

So far, the document provides the most comprehensive requirements in this regard. Article 8 of the outline incorporated the principal party and government officials’ responsibilities for promoting rule of law in the administration of governments into the performance evaluation system, which adjusted the behavioral incentives of the local party and government officials. The strong political motivations as a result of the incentives would transform the promotion of rule of law in administration of governments into real actions, rather than merely political slogans.

III. Operation of the dual governance model

The current governance mechanism for local governments in China consists of both traditional evaluation-based method and law-based method. The latter has been strengthened during the recent years. The two methods have gradually formed a dual governance model for local governments in China.

- Several types of relations between performance evaluation and rule of law

(a) A complementary relationship

Both performance evaluation and rule of law can regulate local government activities. Performance evaluation can make up for the incentives, which administration by law lacks, while administration by law can strengthen the procedural legitimacy of performance evaluation.

First, performance evaluation can be incorporated into existing laws. Performance evaluation is considered a political approach, and excessive use of the approach is considered to affect the legitimacy of governments’ administrative actions. Incorporating performance evaluation into the modern rule of law system not only provides performance evaluation with legal basis, but it also strengthens the binding force of performance evaluation on local governments and ministries. As early as in 1982, Articles 89 and 107 of the Constitution have expressly set out that the State Council and the people’s governments at and above the county level have the right to appoint, remove, evaluate, reward and penalize administrative officials in accordance with the law. More than ten laws, including the Air Pollution Prevention and Control Law, the Sand Prevention and Control Law, the Employment Promotion Law, the Food Safety Law, and the Environmental Protection Law, have stipulated that the local governments must be evaluated on their performance in completing the relevant matters. Performance evaluation is by no means a purely political governance approach outside the current laws, but it has become a legalized governance method.

Second, performance evaluation can promote rule of law. When there is a conflict between rule of law and evaluation items such as political performance and financial indicators, local governments lack incentives to implement rule of law in their administrative actions. For key legal matters closely related to the legitimacy of governance, the central leadership has adopted an approach to advance these matters through performance evaluation. This is due to the high-incentive nature of evaluation performance. When illegal acts give rise to social problems within a particular region, the central leadership will turn to performance evaluation, where it would apply a one-vote veto for those issues that are likely to cause antagonism in the public, and put more weight on those issues that are likely to receive public approval. This is to prevent local governments from failing to comply with the law or failing to enforce the law completely. Some of the exemplary provisions can be found in the Food Safety Law and the Environmental Protection Law. When the central government finally decides to vigorously promote administration by law and set qualifiable evaluation indicators, the local governments have no choice but to obey the decision.

(b) Rule of law weakened by performance evaluation

Promoting rule of law in the administration of government is a low-incentive governance method, while performance evaluation is high-incentive. Once the central leadership adopts the two methods simultaneously, local governments would lean towards performance evaluation rather than administration by law, which will eventually lead to the result where the latter is shelved, alienated, or weakened.

First, it is difficult to quantitively evaluate administration by law. In the lack of full participation of members in the society, change of the central leadership’s governance concept alone will result in local administrative actions being merely an evaluation-driven response. The issued documents, the legal system development goals, and the activities to promote administration by law would all become formalistic.

Second, performance evaluation puts more weight on the excellence of results rather than regulated procedures. Government actions that are useful for evaluation purposes but contrary to the rule of law principles may be treated with lax standards. Particularly, during the time where the economic situation deteriorates and the employment problem is serious, the central leadership would have no choice but to tolerate violations by local governments and adopt an “one eye open and one eye closed” attitude to let go of some activities that are contrary to the law. Those activities will be exempted from penalties, as long as it complies to the governance philosophy of the central leadership.

(c) Performance evaluation replaced by rule of law

Because of the high-incentive nature of performance evaluation, it is easy to cause substitution effects. Therefore, the central leadership would sometimes adjust its governance strategy according to the current situation. For example, when law enforcement is too strong and unregulated, the central leadership will abolish performance evaluation and focus on administration by law. As early as in the last century, the Ministry of Public Security issued a document prohibiting evaluations based on administrative fines, so as not to induce government agencies to conduct phishing law enforcement and use fines to generate income.

- Empirical analysis of the dual governance model

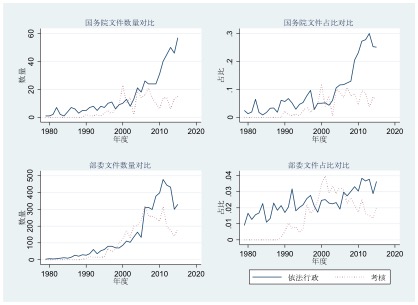

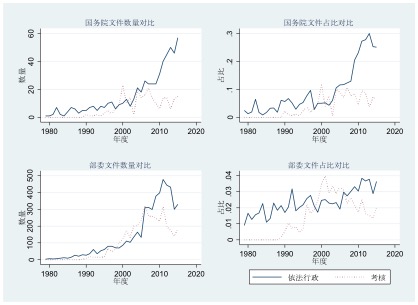

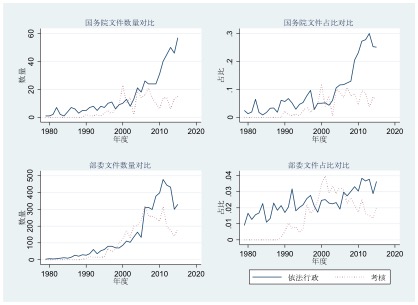

Figure 1: Frequencies of two approaches in official documents

Note: upper pair of panels portray State Council documents, lower pair portrays ministry documents; blue line indicates use of rule of law measure, red line indicates use of performance metrics.

Between 1979 and the end of 2015, 244 documents issued by the State Council and 3,753 regulations and documents issued by the ministries required the implementation of policies through administration by law. On the other hand, the State Council promoted policy implementation through performance evaluation in 567 documents, while the ministries promoted policy implementation through performance evaluation in 5,090 regulations and documents (see Figure 1).

In terms of historical trends, both administration by law and performance evaluation have played an increasingly important role in the implementation of documents issued by the central leadership, and the two have demonstrated a complementary rather than a substitute relationship.

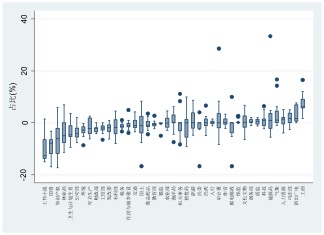

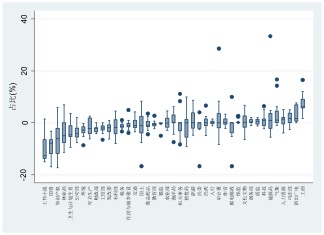

Figure 2 compares different ministries by showing the difference between the proportion of documents using the rule of law approach with a similar proportion using performance metrics. Various ministries have used the dual governance model differently. The industry and commerce ministries have always put more weight on administration by law. The State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) and the environmental ministries have paid more attention to performance evaluation. In general, those that focus more on administration by law include the ministries in charge of food and drugs, human resources, commerce and justice. Those that focus more on performance evaluation include the ministries in charge of finance, taxation, temporary working groups and work safety supervision.

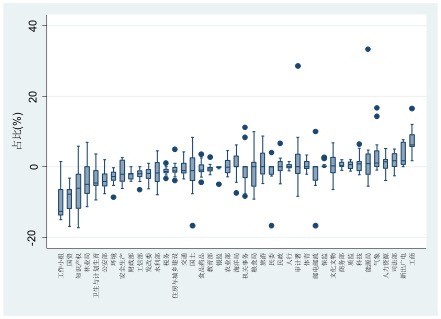

Figure 2 Differential use of rule of law and performance metrics across ministries

IV. Controversy and assessment of the dual governance model

The reasons why the central leadership kept the previously adopted performance evaluation method in promoting rule of law are two-fold. Besides inertial thinking, the more important reason is that law is a strong and stable mechanism to check and balance administrative power. Effective rule of law means a new and independent authority system, as well as relatively more stable and impersonalized implementation of legal provisions. This, however, will weaken the authority of the central leadership and limit its mobilization capacity. In modern China, any modifications of governance methods must be implemented on the basis of ensuring central authority. Therefore, the Regulations emphasize that the principal officials in charge of the party and government must adhere to the leadership of the party. The Regulations require that local party committees serve the core leading role in promoting rule of law in the regions. The Regulations stipulate that the upper level party committees should conduct regular inspections on and provide special supervision to the principal officials of their subordinate party committees with regard to this issue. In 2019, the General Office of the CCP Central Committee and the General Office of the State Council jointly issued the Regulations on the Inspecting Responsibilities in Promoting Rule of Law in the Administration of Government, which discussed the inspections in more details.

Of course, there is a logical conflict in the operation of the dual governance model. It is possible that the authority of the law may be weakened by means of promoting rule of law through performance evaluation. Under the premise of democratic centralism, however, it is not realistic for the CCP to abandon the dual governance model and fully rely on rule of law. It is an arbitrary idea to simply separate and contrast performance evaluation and rule of law. Such an idea does not help to understand China’s governance logic. It also obscures the possibility of building the foundational system for China’s economic and social development. It would fail to provide a possible path to further improve the country’s governance model.

Follow

Follow