Cutting-edge chemistry may be the key to fast and efficient cancer diagnoses. In early 2020, Antonio Wong and his research team at the University of British Columbia (UBC) in Vancouver, BC, developed a new way to synthesize radioactive tracers for positron emission tomography (PET) scan cancer diagnosis. Recently, I interviewed Antonio to discuss his research.

The Problem

Imaging technologies like the CT scan, ultrasound, X-ray, MRI, and PET scans allow doctors to identify cancerous masses in patients. Although PET scans are a common way to diagnose cancer, researchers want to find ways to make tracers more efficiently. So, Antonio and his team aimed to develop a new kind of tracer and to make the synthetic process more efficient.

PET scan and technician, Source: http://www.bccancer.bc.ca

The Science

Since cancer cells divide quickly and uncontrollably, they require many more cellular “building blocks” compared to regular cells. Taking advantage of this, researchers have previously developed “tagged” versions of these building blocks, called tracers, which accumulate inside cancer cells. This allows doctors to see tumors in PET scan images. When I spoke to Antonio, he explained that the “golden standard” for PET imaging uses a sugar molecule called glucose tagged with a radioactive fluoride atom (called FDG) which is responsible for the glow on medical images. To see how tracers work, check out this video below.

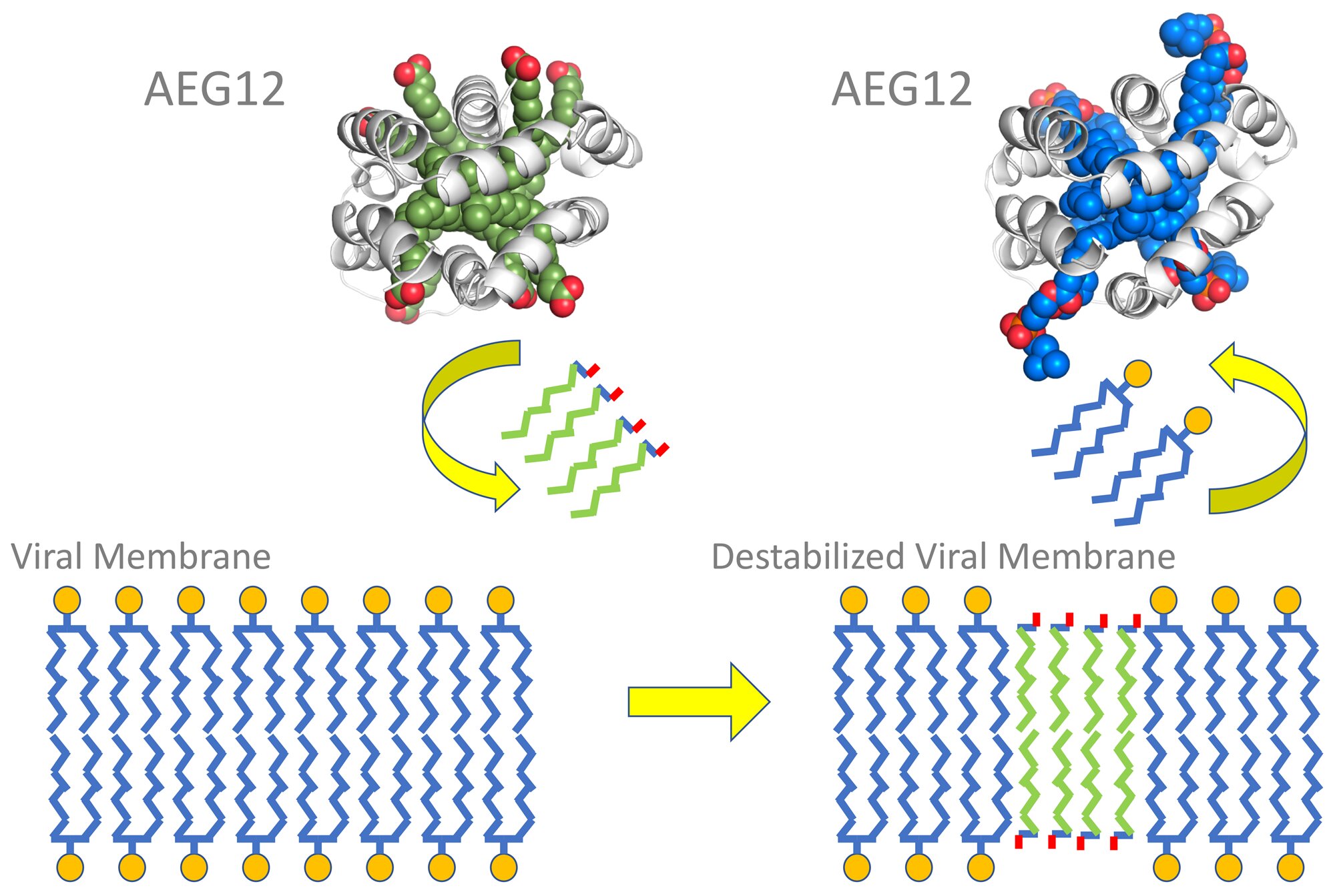

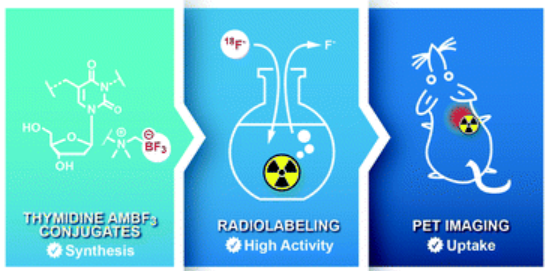

Combining innovation and creativity, Antonio’s team developed a more efficient way to make these tiny building blocks by using a careful mixture of chemicals. They used a molecule called thymidine which is required for cell division, tagged it with a radioactive atom (18F), and injected into mice with cancer. The mice were then put into a PET scan to see if the building blocks were “building up” inside the tumors, which would glow on the PET scan images.

Tracer synthesis, Source: Antonio’s Paper

The Impact

When Antonio ran this study, he was an undergraduate student at UBC. As a result, his story has caught the attention of students on campus. After my interview with Antonio, my colleague Parwaz, a UBC student who runs a podcast called “Thinkin’ a Latte”, chatted with two other UBC undergraduates about the interview. Check out their podcast below.

Although the study’s findings are promising, using thymidine-based tracers for PET tumor imaging requires much more research before it can be used in clinics.

“I think the significance of this paper is not like ‘look this is the next blockbuster drug that we’re trying to use’, this is more like a proof of concept”

– Antonio Wong

Nonetheless, cancer is a prevalent disease that has touched the lives of almost everyone and research like Antonio’s is bringing much needed innovation and creativity to the field.

– Maya Bird

Co-authors: Parwaz, Samin, and Teaya