For the most part, supplementary education research is relatively underdeveloped as an academic specialty.

Supplementary Education on academia.edu

A quick example: on academia.edu, six researchers have joined me in stating their interest as “supplementary education“. I don’t know any of them and six of them list their status as “independent researcher” which doesn’t bode well for someone setting out in an academic career. Is it on-going squabbles about terminology? No, it doesn’t seem to be as neither “shadow education”, “hypereducation” nor “supplemental education” have an entry. There are a ton of entries with “tutoring” as a word, but they are relatively unfocused.

Why No Subdiscipline of Supplementary Education Research

So why has research on supplementary education not established itself? Another way of asking that question is, why are there not more researchers interested in this topic?

For the years that my previous SSHRC grant ran, I was able to recruit a single MA student as an RA. I sent feelers out towards sociology as we as Ed Studies, but found no interest.

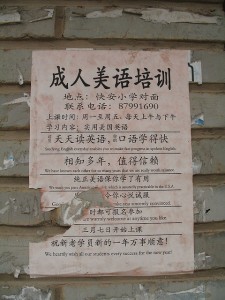

One reason for the sparsity of research is the relatively recent recognition of supplementary education as a phenomenon worth of academic study. In places like Japan, pundits and commentators have written about juku since the 1970s, but this has not led to a research literature. In most OECD countries, the current tutoring/supplementary education boom is a relatively new phenomenon and thus hasn’t attracted a lot of attention yet.

Also, supplementary education sort of sits between all disciplinary chairs. The good thing is that this means it is establishing itself as a genuinely interdisciplinary enterprise which is terrific. This interdisciplinarity not only means a variety of perspectives on the phenomenon (most prominently, perhaps, sociological, but a significant presence of ed studies and pedagogy, coupled with a smaller presence of anthropologists, geographers, economists, etc.), but also means a relatively greater proximity to policy.

Take the example of most education schools: If you look at traditional divisions within the study of education, you will find divisions such as primary, secondary, higher education, or life-long learning, but these examples already suggest that supplementary education doesn’t “fit”. For people focused on schools, juku seem to informal, for life-long learning types 塾生 are too young. That may be why research in this area seems to be coming from neigbouring disciplines rather than education itself in many cases.

CEIS as a Place to Meet

For some time then, the emerging community of supplementary education researchers has been struggling with setting up a centre to its activities or a regular place to meet. Following some discussions last year at the CIES meetings in Montreal, CIES seems to be emerging as a strong contender. Why? It is interdisciplinary, and highlights cross-regional and cross-national comparisons. While CIES is U.S.-based, it has regional and national equivalents throughout the world and a regular global meeting. It meets annually. It is of a nice size, i.e. big enough that participation always seems to yield new insights, but small enough that some lasting links can be built. And finally, it is a pretty friendly conference.

I am aware of several efforts to propose panels that will be focused on supplementary education in Puerto Rico next Spring. One proposal is anchored by Mark Bray of the Univ of HK who generally functions as the godfather to the emerging network of researchers, partly based on his long-standing work in this field, but also partly on his past role as past director of UNESCO’s International Institute for Educational Planning which has given him a wonderful network of researchers around the world.

Hopefully I will be joining with Janice Aurini and Scott Davies – with whom I have collaborated in the past – on a panel proposal as well.

Further Institutionalization

Hopefully, regular meetings of some of the people in this emerging field at CIES will lead to further institutionalization in the form of a community of scholars to whom one can circulate work in progress and with whom one can collaborate on grant proposals and publications.

There is – as of yet – no journal or newsletter that focusses on supplementary education. Yet, there is a growing – albeit informal – network of researchers who focus at least some of their energy on research in this area.