Critical Education

Palestinian Liberation in Education: Solidarities and Activism for a Free Palestine

Special Issue Editor:

Hanadi Shatara

Assistant Professor

California State University, Sacramento

h.shatara@csus.edu

Overview and Aims:

Starting even before 1948, Palestinians and activists for a free Palestine continue to raise global awareness of the oppression and struggles of the Palestinian people. The genocidal events of October 2023 in Gaza along with the continued ethnic cleansing of Palestinians did not happen in a vacuum, but are informed by the historical context of Palestine and the continued activism that has expanded due to social media. Young Palestinian journalists such as Bisan Owda, Plestia Alaqad, and Motaz Azaiza are documenting in real time the atrocities within Gaza (Arafat, 2023) and many young social media consumers are speaking out and becoming civically engaged for Palestine (Roscoe, 2023), all while social media companies are censoring Palestine specific posts (Shankar, et al., 2023). Large scale protests and solidarity rallies for Palestine are happening around the world and almost every continent (Al Jazeera, 2023) with the possibility of free speech under threat in Europe when speaking for Palestine (Rajvanshi, 2023). Organizations led by young people such as the Palestinian Youth Movement, Students for Justice in Palestine university groups, and the Arab Resource and Organizing Center are showing the world capacity and volition for a free Palestine. With the increasing acts of civic engagement, these conversations have permeated into classrooms throughout the world.

Conversations on freedom dreaming for educational justice (Love, 2023) must connect social justice and critical education to Palestinian struggles, activism, and realities, and call for a free Palestine. Several critical education organizations have spoken out for Palestine and provided supports for educators and education researchers to use in their (un)learning. For example, the Abolitionist Teaching Network spoke in solidarity with Palestine on social media and curated resources for teachers in ways to teach Palestine and raise awareness of the liberation movement (Abolitionist Teaching Network, 2023). The Zinn Education Project (2023) in partnership with Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change also provided lessons and other resources to speak about the violence and historical context in Palestine.

Yet, with these avenues of resources, there is much to learn about Palestine in the context of education. Silencing occurs within educational spaces, through social studies and ethnic studies curriculum (Morrar, 2020; Shatara, 2022) and dismissing the experiences of Palestinian young people in schools (Abu El-Haj, 2015; Shatara 2023). For example, in November 2023, a Palestinian American boy was suspended for saying “Free Palestine” when another student called him a terrorist (Conybeare & Ramos, 2023). Given these realities, how do critical educators decolonize their teaching and research to connect to themes of global oppression, resistance, solidarity, freedom dreaming, and liberation for and with Palestine and Palestinians?

Description of Invited Articles:

For this issue, I invite scholars, educators, and activists to connect their work in education to Palestine. I seek submissions for a range of interdisciplinary perspectives, empirical and conceptual research, critical social theoretical framings, and varying formats to engage with solidarities and educational activism for Palestine. Papers can be conceptual, theoretical, empirical with varying critical methodologies. Potential manuscripts can include interviews with Palestinian teachers and activists, book, film, curricula, and media reviews, field reports, as well as traditional academic papers. Some of the questions, but not limited to these, that papers can engage with include:

- What does it mean to be a critical educator with regards to Palestine?

- How can or do educators support the centering and (un)learning of Palestine in critical education work?

- How do global themes of (settler) colonialism, imperialism, oppression, resistance, solidarity, freedom dreaming, and joy connect to the overall mission of critical education?

- How can Critical Race Studies, decolonial and post-colonial theories frame the work in education for Palestine?

- How can teachers and activists work together to teach Palestine in classrooms?

Timeline:

Abstracts (500 words) due to Editor via email (h.shatara@csus.edu): February 28, 2024.

Decisions of Acceptance: March 15, 2024

Manuscript due to Editor: August 9, 2024

Manuscripts under review: August 10 – September 30, 2024

Manuscripts returned to authors for revision: October 11, 2024

Final Manuscript due to Editor: November 8, 2024

Publication of Special Issue: December 6, 2024

About the Editor:

Dr. Hanadi Shatara is an Assistant Professor at California State University, Sacramento. She received her doctorate in Social Studies Education at Teachers College, Columbia University. Her research focuses on critical global education, critical world history, teacher positionalities, the representations of Southwest Asia and North Africa, Palestinian and Arab American teachers, the teaching of Palestine, and teacher education. Her work is published in The Critical Social Educator, Social Studies and the Young Learner, Social Studies Research and Practice, and Curriculum Inquiry. She has also published several book chapters with the most recent called “This is not about religion: Troubling the perceptions of Palestine and Palestinians” with co-author Dr. Muna Saleh in the edited volume Religion, the First Amendment, and Public Schools: Stories from K-12 and Teacher Education Classrooms. Dr. Shatara was also a middle school social studies teacher for seven years in Philadelphia, PA, where she became a National Board Certified Teacher.

About Critical Education:

Critical Education is an international, refereed, open access journal published by the Institute for Critical Education Studies (ICES). Contributions critically examine contemporary education contexts, practices, and theories. Critical Education publishes theoretical and empirical research as well as articles that advance educational practices that challenge the existing state of affairs in society, schools, higher education, and informal education. ICES, Critical Education, and its companion publication Workplace: A Journal for Academic Labor, defend the freedom, without restriction or censorship, to disseminate and publish reports of research, teaching, and service, and to express critical opinions about institutions or systems and their management. Co-Directors of ICES, co-Hosts of ICES and Workplace blogs, and co-Editors of these journals resist all efforts to limit the exercise of academic freedom and intellectual freedom, recognizing the right of criticism by authors or contributors.

Author Guidelines: https://ices.library.ubc.ca/index.php/criticaled/about/submissions

References

Abolitionist Teaching Network [@ATN_1863]. (2023, November 17). Our schools continue to be a vital space for teaching and organizing for a free Palestine. Here are a few resources to inspire conversations in your classrooms. Comment ⬇️ with materials & lesson plans you’re finding inspiring & activating #Educators4Palestine [Images attached] [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/ATN_1863/status/1725700843729473713?s=20.

Abu El-Haj, T. R. (2015). Unsettled Belonging: Educating Palestinian American Youth after 9/11. University of Chicago Press.

Al Jazeera. (2023, November 17). In photos: People protest Israel’s war on Gaza across the world. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/gallery/2023/11/17/photos-people-protest-israeli-war-on-gaza-across-the-world.

Arafat, Z. (2022, December 29). Gaza through my Instagram feed. New York Magazine. https://nymag.com/intelligencer/article/bisan-plestia-motaz-gaza-through-my-instagram-feed.html.

Conybeare, W. & Ramos, A. R. (2023, November 15). Orange County student suspended for saying ‘Free Palestine,’ family claims. KTLA. https://ktla.com/news/local-news/orange-county-student-suspended-for-saying-free-palestine/#:~:text=The%20family%20of%20a%20student,being%20suspended%20for%20three%20days.

Love, B. (2023). Punished for dreaming: How school reform harms Black children and how we heal. St. Martin’s Press.

Morrar, S. (2020, November 6). Changes to ethnic studies in California include expansion on Asian American lessons The Sacramento Bee. https://www.sacbee.com/news/local/education/article247016937.html.

Rajvanshi, A. (2023, October 23). Europe’s balancing act: Protecting free speech while curbing anti-Israel rhetoric. Time. https://time.com/6326360/europe-palestine-protests-free-speech/.

Roscoe, J. (2023, November 13). TikTok: It’s not the algorithm, teens are just pro-Palestine. Vice. https://www.vice.com/en/article/wxjb8b/tiktok-its-not-the-algorithm-teens-are-just-pro-palestine.

Shankar, P., Dixit, P., & Siddiqui, U. (2023, October 24). Shadowbanning: Are social media giants censoring pro-Palestine voices? Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2023/10/24/shadowbanning-are-social-media-giants-censoring-pro-palestine-voices.

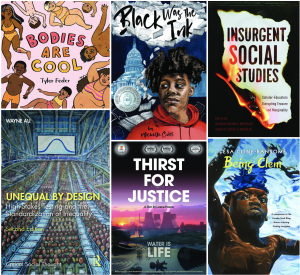

Shatara, H. (2022). “Existence is Resistance”: Palestine and Palestinians in social studies education. In S. B. Shear, N. H. Merchant, & W. Au (Eds.), Insurgent social studies: Scholar-Educators disrupting erasure & marginality. Myers Education Press.

Shatara, H. (2023). Critical Political Consciousness within Nepantla as Transformative: The Experiences and Pedagogy of a Palestinian World History Teacher. Curriculum Inquiry. 53(1), 28-48. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.2022.2123214

Zinn Education Project. (2023, December 4). Teaching About the Violence in Palestine and Israel. Zinn Education Project. https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/violence-in-israel-and-gaza/.