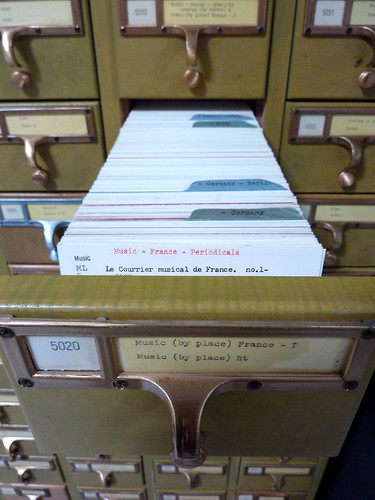

Library card catalog shared CC by John Kannenberg

I got my first experience of this reality when I was a graduate student of literature in the mid-1990’s. Back then [cue nostalgic music], if someone needed to assemble a list of references to research a given topic, at least part of the process worked something like this:

* Consult the print index of the Modern Language Association (MLA) International Bibliography, a massive multi-volume reference work that purported to index all scholarship in the field over the previous decade or so. Most major research university libraries could afford an updated set every couple of years. There was a separate set that indexed older works, nearly as large. Because of the sheer size and value of the reference books, they could not be taken out of the library. Scholarly publications were indexed by keywords, authors, and broader subjects such as literary themes. But obviously, due to the limitations of print, the number of entries and the number of places an item could be indexed in the volumes were limited. You were not likely to find entries published in non-traditional sources, and you had to know almost exactly what subjects and keywords you were looking for before you began looking.

* As you wade through the volumes of the MLA International Bibliography, carefully write down by hand the citation information for articles that might prove to be useful.

* With your list of possible sources in-hand, consult a library card catalog — a rack of small wooden drawers containing index cards listing the contents of that particular library. One by one, you would hunt through these cards to see if the research journals or books you were looking for were available at your library. If they were not, you could either strike that option off your list, or if it looked particularly important you might initiate the lengthy and occasionally costly processes involved with an inter-library loan. (Assuming of course you were not beginning your research two or three days before the deadline.) If the item was available, you wrote down the location in the library stacks where it might be found.

* Wander the stacks of the library, gathering large volumes (when they were indeed on the shelves, when they were not checking the shelving point and the carts and hoping for the best), each one containing a 15-20 page article that may or may not prove relevant.

* Since periodicals usually could not be taken out of the library, set up with a photocopier and copy each article by hand, one page at a time. Copies not cheap, especially when your income comes from student loans and part-time minimum wage jobs.

* Take home your stack of articles and finally get the chance to read them properly. Realize that at least half of them are not as relevant as they once seemed, and that many others are devoid of anything like useful information or insight.

* Plan another trip to the library.

This cumbersome process actually involved something resembling skill, some people were better at it than others. We took orientation classes in “research methods” to learn the basics. Because I worked part-time at the library while a student, I was something of a savant at gathering research — I could usually get most of what I needed for a short paper in only four or five hours! My ability to work the stacks was something that gave me an edge as a student, and I assumed this ability would serve me well as a scholar for many years.

Just before I finished my Masters, I was walking through the library and noticed tables loaded with shiny new computer terminals, and that one of them was set up with a CD-ROM version of the MLA International Bibliography. Out of curiosity I sat down and entered a few queries. I realized that my hard-earned foundational skills as a scholar could be easily surpassed by any newcomer with the ability to type a few words into a search box. What had once taken long hours of careful process could now be done in a few minutes, and with tools far more forgiving of error. I had spent years developing abilities that were rendered obsolete in an instant. As I recall, this realization left me with a sense of euphoria.

And of course the context of searching, identifying, gathering and reproducing information has only continued to evolve with dizzying speed. With so much changed about how research is now performed, what amazes me most is how little has changed with scholarship itself. Literary studies incorporate references exactly as they did back when I gathered them by hand. Articles are evaluated the same way. They are published in more or less the same places, in many cases more expensive for libraries to acquire than they were fifteen years ago. And if you do not belong to an authenticated university computer network, these works are effectively inaccessible to you.

Some things do not change so easily. It’s a race against obsolescence.

Pingback: Tweets that mention New post on the Abject: Modern scholarship is a race against its own obsolescence. -- Topsy.com

Pingback: Crónica de una semana agitada. Un seminario intensivo en tecnología educativa edupunkeana — Filosofitis

Pingback: Interlink Headline News Nº 5651 del Miércoles 21 de Julio de 2010 | InterLink Headline News 2.0

Here’s the thing (and I know I’m going to come off sounding like such a cranky old person when I say this): although the specific research skills you developed are totally obsolete, the other kinds of skills you had to develop along the way, in terms of the critical thinking and problem solving skills that got practiced when you hit those research dead ends, serve you to this day. And I’m not sure that scholars of the Google age are developing these same skills. Back in the day, they were acquired sort of as a byproduct, through the sheer need of having to get those reference sources. But today – where you can find a decent number of passable to good sources while waiting for your buddy to reply to an IM – where are these skills and habits being practiced?

I know there’s a whole emergent body of literature out there on What Google Hath Wrought Upon Our Brains (the latest being Nicholas Carr) and while I believe that it’s wiring brains in all kinds of new and different ways that we can’t yet understand, I still think (and here comes you-kids-get-outta-my-yard mode again) that there’s something to be said for the research tenacity, craftiness, and prolonged attention that comes as part of the old-school research process. It’s sort of like the ability to build a table from scratch: it’s easier and probably a better use of my time to just go to IKEA and buy a table, but if I had to build my own furniture I would be forced to develop all these other kinds of construction, spatial visualization, coordination and motor skills that would serve me well in other areas of my life.

Thankyou Brian, nice article.

You touched on some important points at the end, and they should be developed further – namely:

“They are published in more or less the same places, in many cases more expensive for libraries to acquire than they were fifteen years ago. And if you do not belong to an authenticated university computer network, these works are effectively inaccessible to you.”

Scholars, who have already been paid by governments and grants, should not have their work locked up by digital distributors who profiteer and charge exhorbitant rates for access to scholarship on the Internet.

It prevents the spread of global knowledge, and brings academics and their work into disrepute. Many of the scholars I knew in late 1990s went into paranoid fits over the development of the Internet and the digital assault on their ivory towers. Is this unholy alliance with publishing companies the revenge of the anti-nerds whose comfortable little worlds have been disrupted?

For those scholars who share their work freely and use the Internet for the benefit of all – I say, Welcome to the New World, you are finally one of us.

Pingback: Why Should Academics Develop Their Course Materials in Public…? « OUseful.Info, the blog…

Adrienne – Crankiness is always welcome on The Abject, especially when it is in the service of such thoughtful observation. I agree that the foundational work I did in the analog world learning those skills has probably served me well in my current work. Of course, not in terms of actual skills, but in terms of process, habit, and temperament. I could make that general assertion about my graduate studies in general. I feel fortunate to have been educated in a time when education still had a very broad orientation in this regard, and worry we may be losing that… Personally, I don’t blame technology so much as the increasing need to program teaching and learning so tightly, things are so much more structured and organized now. But your points stand quite well on their own. Thanks!

Michael, well said. I’ve been trying to write some material lately on how the closed nature of academic publishing feeds a disconnect with the wider public, and you articulate that sense far more directly and passionately than I seem able to do.

Speaking of “euphoria,” I find it quite cheering that the skills acquired while pursuing a graduate degree in literature [okay, and working in the library] can be transformed into the work you’re currently doing. (But then, I’m always cheered by evidence that supports the value of a liberal arts education.)

Like Adrienne (and I admit to my own fair share of crankiness), I suspect that there’s more depth to the skills you acquired during your graduate studies and research than is perhaps readily apparent. Although certainly the newer search technologies have taken over part of the human function (and do some things better), but I’m not ready to cave completely just yet! 🙂

I also agree with Michael’s comments: “Scholars, who have already been paid by governments and grants, should not have their work locked up by digital distributors who profiteer and charge exhorbitant rates for access to scholarship on the Internet.” Norm Friesen recently presented on this topic at TRU while promoting to faculty the use of open access journals for publishing their research.

Best of luck with your closing keynote at the OERs symposium!