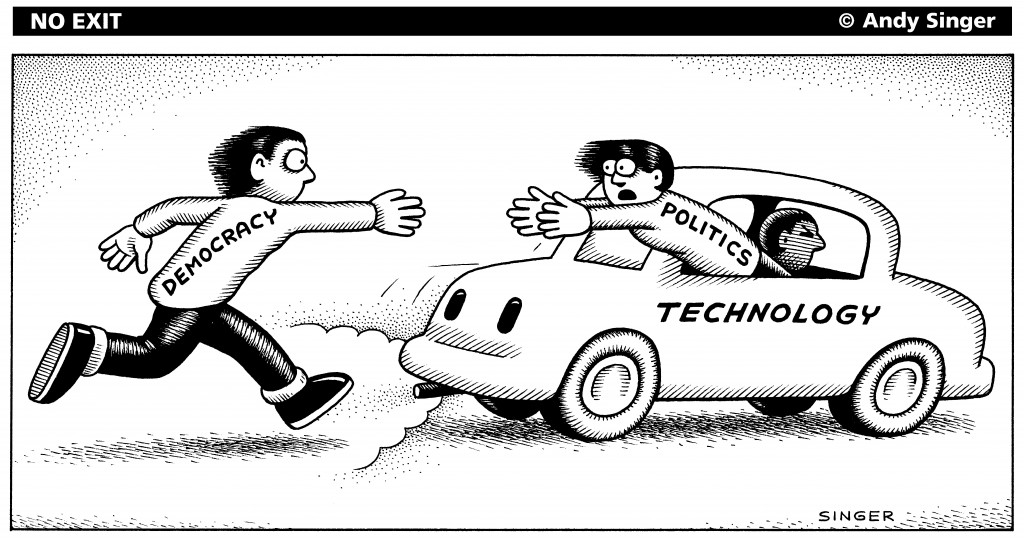

Cartoon purchased from cagle.com for use in this project.

There is, in the world, real and perceived social and economic gaps that exist between cultures, societies, countries and even within such geopolitical entities. These gaps or divides often separate the world into those who have and those who have not, feed local and global conflicts, drive environmental degradation, marginalize groups and individuals, and are perpetuated by economic interests and political power. Technology, of course, is often considered to be central to such divides. At the same time, technology is also looked to and advanced in ways that potentially bridge and eliminate such divides. Further, there is at present a divide that exists within context of advancing technologies called the digital divide where some across the globe have access to 21st century technologies while others are seemingly excluded. It is from these contexts that the role of technology will be considered here. More specifically, by comparing and contrasting perspectives on writing and print technologies with emerging perspectives on digital technologies and examining ideas around the neutrality of technology, in the work of Ong (1982), Postman (1992), Chandler (1994) and Petrina (2008), we can better understand the role of technology in the potential creation and elimination of social, economic, and political inequities mentioned above.

In chapter 4 of his text Orality and Literacy, Ong (1982) posits that writing, with its use of tools and artificial orientation, is to be considered a technology. Further, Ong articulates that print technologies and digital (computer) technologies are then extensions and evolutions of this original ‘drastic’ technological leap from orality. For Ong the literate culture supported by writing and print technologies is one that is fundamentally different from purely oral cultures where human consciousness is transformed and a deeper human potential can be realized. If we accept this perspective it would follow that those who have access to such a technology would have an advantage over those who did not.

Gleaned from Ong’s discussion and text is the idea that as written or print literacy takes hold in a culture the significance of print begins to provide, not only deeper intellectual affordances but also, real political power where the (real or perceived) legitimacy of written literacy trumps that of oral literacy. The use of the written word in law and court proceedings stands as an example here. In the development and evolution of print literate cultures some groups adopt and gain access to this technology before others. When print begins to wield political power this puts a knowledge power structure in place that create inequities. Ong outlines this ‘power monopoly’ as he casts the light on various early written languages that became the exclusive domain of an exclusive male culture. This theme of technology politics is present in the discourse and spread of modern digital technologies.

The lack of political neutrality inherent in modern technologies including digital technologies is seen to have created a divide where some experience political and economic power while others are left out (Chandler, 1994; Postman, 1992; & Petrina). In Chandler’s (1994) review of literature on this theme the inherent biases built into technologies including beliefs about progress, modernity, and the resulting social structures that use and are influenced by technologies is explored as evidence of the technological determinism and lack of neutrality present in technology. In his reflections on writing technologies and computer technologies, Postman’s (1992) Thamusian skepticism is framed by the idea of technology being intrinsically non-neutral. He questions the power inequity that is established when a perceived wisdom and reverence that is granted to those who are knowledgeable in relation to particular technologies. Further, among other criticisms Postman suggests that the ideologies, values and beliefs that are part of the technological design process are complicit in putting the values of one perspective over another, or more succinctly a society of winners and losers.

It is interesting to consider the pessimistic classroom computer use example Postman uses near the end of his, now somewhat dated, chapter ‘The Judgement of Thamus.’ Here he offers support for his position of technology carrying a bias by suggesting that the use of computers in classrooms, by their design, will be likely to result in an academic culture that is purely isolated, individualistic, and lacking in community. This of course seems antithetical to much of the learning theory embedded in educational technologies that promote collaboration, open dialogue and, a cultivation of a community of learners. Petrina (2008) although equally skeptical of the underpinning biases inherent in technologies offers a competing view of educational technologies to that put forth by Postman.

In his work, Petrina (2008) urges educators to avoid the autonomous learning culture Postman hypothesizes. The suggestion is that by embracing open-source technologies that are by nature communally developed educators will be supporting learning that is collaborative. Further, supporting open access and the free circulation of ideas we can move closer to the virtues of learning in oral cultures where cooperation, community and social responsibility are emphasized (Postman, 1992; p. 17). Still technology has always been looked to as a panacea for bridging political and cultural divides and if the logic follows open-source technologies too are not neutral and will contain a bias that supports one view at the expense of another as Postman, Chandler and Petrina have suggested.

References:

Chandler, D. (2000). Technological or media determinism. Retrieved from http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/tecdet/tdet01.html

Ong, Walter. (1982.) Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. London: Methuen.

Postman, N. (n.d.). Technopoly: The surrender of culture to technology. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Petrina, S. (2008). The Politics of Educational Technology, Module 5, 1.1 Politics,

Technology and Values. Retrieved November 7, 2008, from https://www.vista.ubc.ca/webct/urw/lc5116011.tp0/cobaltMainFrame.dowebct

Neutrality and Politics in Print and Digital Technologies

Cartoon purchased from cagle.com for use in this project.

There is, in the world, real and perceived social and economic gaps that exist between cultures, societies, countries and even within such geopolitical entities. These gaps or divides often separate the world into those who have and those who have not, feed local and global conflicts, drive environmental degradation, marginalize groups and individuals, and are perpetuated by economic interests and political power. Technology, of course, is often considered to be central to such divides. At the same time, technology is also looked to and advanced in ways that potentially bridge and eliminate such divides. Further, there is at present a divide that exists within context of advancing technologies called the digital divide where some across the globe have access to 21st century technologies while others are seemingly excluded. It is from these contexts that the role of technology will be considered here. More specifically, by comparing and contrasting perspectives on writing and print technologies with emerging perspectives on digital technologies and examining ideas around the neutrality of technology, in the work of Ong (1982), Postman (1992), Chandler (1994) and Petrina (2008), we can better understand the role of technology in the potential creation and elimination of social, economic, and political inequities mentioned above.

In chapter 4 of his text Orality and Literacy, Ong (1982) posits that writing, with its use of tools and artificial orientation, is to be considered a technology. Further, Ong articulates that print technologies and digital (computer) technologies are then extensions and evolutions of this original ‘drastic’ technological leap from orality. For Ong the literate culture supported by writing and print technologies is one that is fundamentally different from purely oral cultures where human consciousness is transformed and a deeper human potential can be realized. If we accept this perspective it would follow that those who have access to such a technology would have an advantage over those who did not.

Gleaned from Ong’s discussion and text is the idea that as written or print literacy takes hold in a culture the significance of print begins to provide, not only deeper intellectual affordances but also, real political power where the (real or perceived) legitimacy of written literacy trumps that of oral literacy. The use of the written word in law and court proceedings stands as an example here. In the development and evolution of print literate cultures some groups adopt and gain access to this technology before others. When print begins to wield political power this puts a knowledge power structure in place that create inequities. Ong outlines this ‘power monopoly’ as he casts the light on various early written languages that became the exclusive domain of an exclusive male culture. This theme of technology politics is present in the discourse and spread of modern digital technologies.

The lack of political neutrality inherent in modern technologies including digital technologies is seen to have created a divide where some experience political and economic power while others are left out (Chandler, 1994; Postman, 1992; & Petrina). In Chandler’s (1994) review of literature on this theme the inherent biases built into technologies including beliefs about progress, modernity, and the resulting social structures that use and are influenced by technologies is explored as evidence of the technological determinism and lack of neutrality present in technology. In his reflections on writing technologies and computer technologies, Postman’s (1992) Thamusian skepticism is framed by the idea of technology being intrinsically non-neutral. He questions the power inequity that is established when a perceived wisdom and reverence that is granted to those who are knowledgeable in relation to particular technologies. Further, among other criticisms Postman suggests that the ideologies, values and beliefs that are part of the technological design process are complicit in putting the values of one perspective over another, or more succinctly a society of winners and losers.

It is interesting to consider the pessimistic classroom computer use example Postman uses near the end of his, now somewhat dated, chapter ‘The Judgement of Thamus.’ Here he offers support for his position of technology carrying a bias by suggesting that the use of computers in classrooms, by their design, will be likely to result in an academic culture that is purely isolated, individualistic, and lacking in community. This of course seems antithetical to much of the learning theory embedded in educational technologies that promote collaboration, open dialogue and, a cultivation of a community of learners. Petrina (2008) although equally skeptical of the underpinning biases inherent in technologies offers a competing view of educational technologies to that put forth by Postman.

In his work, Petrina (2008) urges educators to avoid the autonomous learning culture Postman hypothesizes. The suggestion is that by embracing open-source technologies that are by nature communally developed educators will be supporting learning that is collaborative. Further, supporting open access and the free circulation of ideas we can move closer to the virtues of learning in oral cultures where cooperation, community and social responsibility are emphasized (Postman, 1992; p. 17). Still technology has always been looked to as a panacea for bridging political and cultural divides and if the logic follows open-source technologies too are not neutral and will contain a bias that supports one view at the expense of another as Postman, Chandler and Petrina have suggested.

References:

Chandler, D. (2000). Technological or media determinism. Retrieved from http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/tecdet/tdet01.html

Ong, Walter. (1982.) Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. London: Methuen.

Postman, N. (n.d.). Technopoly: The surrender of culture to technology. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Petrina, S. (2008). The Politics of Educational Technology, Module 5, 1.1 Politics,

Technology and Values. Retrieved November 7, 2008, from https://www.vista.ubc.ca/webct/urw/lc5116011.tp0/cobaltMainFrame.dowebct