An example of braille integrated into another assistive device, in this case a handrail at a Japanese train station (photo taken by Brian Farrell in Tokyo, Japan, October 17, 2010).

In a society that places a high value on the ability to read and write, those with visual disabilities were once at a tremendous educational loss and not able to participate fully in society. The current technology available to those with physical disabilities today is extensive, and now means that many more people are now able to access, read, and author written texts. In the course of our history though, this is a change that has only occurred recently, and assistive technologies such as the braille system have been incredibly important in driving this change.

Braille is a standardized and tactile system that was developed by a blind man faced with the inability to view, and therefore read standard texts. In 1829, Louis Braille codified and developed a system of raised dots that would allow blind readers to use touch to discover texts, and while some modifications and additions have occurred, this same system largely remains in use today. Braille was inspired to create his system after learning about a military system using raised dots that would allow soldiers to communicate in the dark and without speaking aloud (Canadian National Institute for the Blind, 2010).

Rather than a distinct language, braille is a system of writing, reading, and transferring knowledge. Based upon the standard roman alphabet, braille also incorporates other written symbology such as punctuation and letter accents, without which the organization of written texts could prove difficult. This is an important distinction of braille from other reading technologies for the visually impaired, as it places an emphasis on the written word as it would be viewed by a sighted person. Where an audio recording may also serve to deliver a written body of work, its absence of explicit punctuation means that this technology may limit the listener’s understanding of standard grammatical structure used in writing.

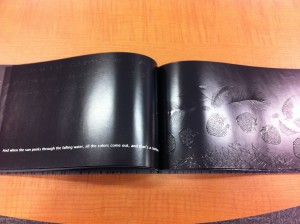

Braille is but one example of raised print used to express meaning to a reader (photo by Brian Farrell of Menena Cottin's "The Black Book of Colors", Groundwood Books, Toronto, 2009).

Similar to learners of other languages, learners of braille may gain an ability to read and access texts at differing levels. Like any other learners, “…findings show that braille patterns are processed in a variety of different ways by different people and in different conditions” (Millar, 1997, p. 249). It is certainly possible for one to have a learning or other disability in addition to a visual impairment, and so the education of a braille reader needs to be differentiated much in the same way that it may be for a fully sighted learner.

Unfortunately, the adoption of braille has not been incredibly widespread. Other assistive technologies such as audio recordings of written texts are often preferred, as they do not require the listener to have any special knowledge of the unique braille reading system. Braille requires an upfront commitment to learn and understand a formulaic system of communication, and in the case of someone who is born blind, this development occurs when a learner is also trying to gain a grasp of a language in its audio or spoken form. While this is realistically similar to the effort required of a sighted learner who is first learning to decode our written structures, the fact that there are other audio alternatives available for visually impaired learners can often mean that braille is not fully pursued. Indeed it has been estimated that braille readers constitute, “…fewer than 10 percent of the estimated number of persons who are legally blind in the United States and slightly fewer than 40 percent of the estimated number who are ‘functionally blind’ (defined as those whose ability to see is light perception or less).” (National Federation of the Blind, n.d.) This can easily create a vicious cycle, as fewer users of an assistive technology such as braille mean a corresponding decrease in those able to teach and transfer this knowledge to a new generation.

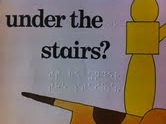

Braille incorporated alongside typed text (photo by Brian Farrell of Eric Hill's "Where's Spot", Ventura Publishing Ltd., London, 1988).

Like other writing systems, braille does have its limitations in functionality. Legibility can often become a problem, as a text can easily become altered by a reader who presses too hard on the pages on which it is transcribed, creating changes in the level of braille dots on the page (Millar, 1997, p. 138). Similar alterations can occur if a braille text becomes worn or otherwise damaged, and these frustrations are compounded by the fact that a blind reader, obviously unable to visually inspect a paper book, will not discover these deficiencies until he or she attempts to access the text.

Further, the requirement to indicate each letter of a word separately can mean that braille texts are many pages longer than their roman alphabet written counterparts. This challenge has meant that several systems, or ‘grades’ of braille have emerged, each with different characteristics. Grade one braille is a system that replicates only the 26 letters of the alphabet and punctuation, grade two braille, the most common system in use, incorporates contractions to shorten words, and grade three braille goes even further in shortening entire words to serve as a sort of shorthand (Omniglot, 2010).

Due to its historical era of creation, braille has been a pioneer system in advancing the abilities and education of previously disadvantaged and disabled people. While many more advanced and technical systems have emerged since the advent of braille, the idea of creating a system that would allow the blind to read the same texts as sighted people meant that an enormous gap in understanding and education for the blind could be bridged. Of course, the functionality of such a system can often depend on the assistance of those without a visual disability, and the limited portability of large braille texts has meant that digital audio solutions for the blind have thrived as an alternative.

The implementation of braille has meant a heightened awareness of the needs of those with disabilities, and the system has served as a model for further developments. The very idea of non verbal communicating by touch and feel has been applied to a variety of applications. Sidewalk strips using raised plastic guides of different levels that can be felt underfoot, braille-like dots on paper currency, and employing a variety of different edging, shapes, and sizes of coins are all similar applications. While many of these advancements are primarily intended to benefit the visually impaired, they can often prove useful to a sighted individual, and they do serve to heighten an awareness of the needs of others.

The future of printed text appears to be in flux with the advent of more and more advanced digital technologies, and braille is undergoing a similar period of questioning and transition. Still, braille remains an incredible enabler in breaking down traditional barriers, and its highly codified and touch-based foundations have served to expand the possibilities of non verbal communication for us all.

Highly visible and physically raised plastic panels along a walkway (photo taken by Brian Farrell in Yokohama, Japan, October 17, 2010).

Bibliography

Canadian Braille Authority. (2010). About Braille. Retrieved October 16, 2010, from http://www.canadianbrailleauthority.ca/en/about_braille.php

Canadian National Institute for the Blind. (2010). Biography of Louis Braille. Retrieved October 14, 2010 from http://www.cnib.ca/en/living/braille/louis-braille/

Canadian National Institute for the Blind. (2010). Braille Literacy. Retrieved October 14, 2010, from http://www.cnib.ca/en/living/braille/literacy/

Millar, S. (1997). Reading by Touch. London, UK: Routledge.

National Federation of the Blind. (n.d.). Estimated Number of Adult Braille Readers in the United States. Retrieved October 14, 2010, from http://www.braille.org/papers/jvib0696/vb960329.htm

Omniglot. (2010). Braille. Retrieved October 16, 2010, from http://www.omniglot.com/writing/braille.htm

Brian Farrell

Is there an app for that? Without much knowledge in the subject I am interested in how effective mobile technology apps are for disability services. I would think there are a few systems and programs other than braille undergoing massive change.

Great reading. Thanks Brian.