Hello classmates,

I have decide to submit my assignment a few ways. First you will find a video I made (I am a amateur); next you will find a transcript of what I said in the video; finally is the transcript copied into this post.

I made a video for three reasons:

- Deaf students (as it was explained to me) are very similar to ESL students in that they prefer their mother-tongue. Sign language is “their” mother-tongue; written or spoken language is foreign to them. Also, like non-hearing impaired students, some are visual learners. This video is intended to provide accessibility to the deaf and hearing-impaired.

- Some have never seen sign language “in action”. Hopefully this will provide visual evidence of what sign language looks like.

- The video (which has no sound) is intended to show you – the viewer – what a deaf or hearing-impaired person deals with every day.

I hope you enjoy!

~ Ryan

_____________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________

The Recognized Origins of Sign Language

Have you ever imagined what your life would be like if you were unable to hear. What it would be like if you couldn’t hear the roar of the crowd as your favourite sports team clinched the championship? What if you couldn’t hear your child’s first words? For most people this is not something they will ever have to consider. But for many, this is their reality. In current times, deaf people are integrated into “regular” educational settings. Obviously they face barriers and obstacles that their non-hearing impaired counterparts do not. However, through the practice of sign language and other techniques such as lip reading deaf people have become productive, active and respected members of today’s classrooms – but it hasn’t always been this way.

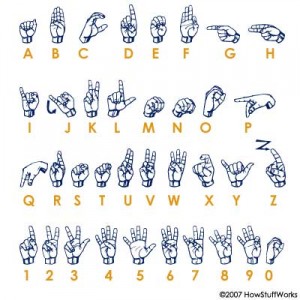

Sign language is a visually-based language that uses hand gestures, body language and facial expressions as a form of communication for the deaf.  Relatively speaking, sign language is a new language (with respect to world-wide acceptance) but it does have a very long and storied history. One might be amazed to learn that nearly 2,500 years ago Socrates (in Plato’s Cratylus) made reference to deaf people using signs: “If we hadn’t a voice or a tongue, and wanted to express things to one another, wouldn’t we try to make signs by moving our hands, head, and the rest of our body, just as dumb people do at present?” (Wikipedia.org, Sign Language, ¶ 3). Today, there are literally hundreds of different types of sign languages (click here for a list of different sign languages). In Africa alone there are more than thirty different types. In North, Central and South America there are another twenty-five plus languages used. And, much like individual languages native to countries, towns, and villages, there are several dialects, syntax and structure that set each and every language apart (Fleming, 2002). Therefore, it would be naïve to conclude that a deaf person from Canada would be able to easily communicate with a deaf person from France.

Relatively speaking, sign language is a new language (with respect to world-wide acceptance) but it does have a very long and storied history. One might be amazed to learn that nearly 2,500 years ago Socrates (in Plato’s Cratylus) made reference to deaf people using signs: “If we hadn’t a voice or a tongue, and wanted to express things to one another, wouldn’t we try to make signs by moving our hands, head, and the rest of our body, just as dumb people do at present?” (Wikipedia.org, Sign Language, ¶ 3). Today, there are literally hundreds of different types of sign languages (click here for a list of different sign languages). In Africa alone there are more than thirty different types. In North, Central and South America there are another twenty-five plus languages used. And, much like individual languages native to countries, towns, and villages, there are several dialects, syntax and structure that set each and every language apart (Fleming, 2002). Therefore, it would be naïve to conclude that a deaf person from Canada would be able to easily communicate with a deaf person from France.

Much like anything, sign language evolved out of necessity. Dating back to the beginning of time, deaf people were considered unteachable (Fleming, 2002). Deaf students were not allowed in “regular” schools and were considered to be of little worth. For all intents and purposes communication between the hearing impaired and non-hearing impaired did not exist. Whether it was due to frustrations or ignorance, deaf people were shunned by society. One could argue that if not for the creation of sign language, deaf people would be living their lives in complete obscurity.

Individuals with the ability to hear believed that deaf people could not communicate. However, deaf people have always been able to “speak” with one another. Even in its infant stages of evolution sign language employed movements, gestures, body language and elementary signs that allowed deaf individuals to communicate with one another. When deaf people would meet they would share signs and take what they had learned and share it with others. In this sense, sign language is very much like any other oral-based language.

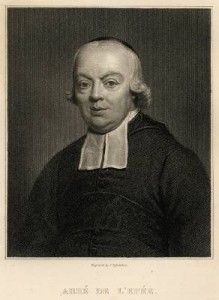

It is widely accepted that sign language has European origins – France to be specific. In the late 1700’s, French author Abbé Deschamps declared that the deaf community had developed a system of communication through hand movements (Fleming, 2002). It was from this that the first school for the deaf was born in Paris, France in 1755 by Abbé Charles-Michel de L’Épée.  Épée revolutionized sign language by building on what was already in place. He wasn’t interested in radically changing the current state of sign language but he knew that for it to gain acceptance he had to build on what already preexisted. By adding common signs and tweaking sentence structure, sign language more closely resembled French grammar. Because sign language now mimicked French language and grammar structure, it was able to gain that acceptance that Épée sought (albeit still unofficially). Épée was such a success that educators from all over Europe copied what he was doing. Even educators from America travelled to France to study sign language and learn from Épée’s structure. Although sign language had been around for centuries (even millenniums in its purest form) it was Épée’s school that most consider to be the true origin to which all modern sign languages were born.

Épée revolutionized sign language by building on what was already in place. He wasn’t interested in radically changing the current state of sign language but he knew that for it to gain acceptance he had to build on what already preexisted. By adding common signs and tweaking sentence structure, sign language more closely resembled French grammar. Because sign language now mimicked French language and grammar structure, it was able to gain that acceptance that Épée sought (albeit still unofficially). Épée was such a success that educators from all over Europe copied what he was doing. Even educators from America travelled to France to study sign language and learn from Épée’s structure. Although sign language had been around for centuries (even millenniums in its purest form) it was Épée’s school that most consider to be the true origin to which all modern sign languages were born.

Sign language was now acknowledged to be a true language even though governing bodies weren’t so quick to officially recognize it. Most sign languages are not exact spoken languages. What this means is that typically sign language is not directly translatable into a given spoken language. Also, those learning sign language (that are not hearing impaired) often struggle because they think in terms of signing words and following spoken grammar rules rather than focusing on concepts. When trying to learn sign language, the biggest hurdle to overcome is to try and stop thinking in words. For these reasons Governments weren’t quick to adopt sign language as a true language. In the late 1700’s and early 1800’s governments merely viewed sign language as a tool or gadget to teach the deaf rather than as a language. There are many examples throughout history where society is slow in adopting and accepting what is initially unknown or unfamiliar. Sign Language is just another such case. To say governing bodies were slow to recognize sign language as an official language is an understatement. The important thing is they now have.

Aspects of sign language are not that different from most spoken oral languages. Take English as an example. One could argue that there are two types of English language. That what is taught in the classroom and that what is spoken outside of the classroom. In school we are taught proper sentence structure, grammar rules, and syntax. Outside of school many of the rules we are taught cease to exist yet we can still understand one another and communicate effectively. What was occurring in the deaf community was no different. Students were taught rules and structure that closely resembled formal oral teachings yet students were not following these rules in informal settings. Eventually, these two types of sign language (both formal and informal) morphed into a common language known today as the American Sign Language (ASL) (Berke, 2010). This is important because ASL is generally regarded as being “one of the most comprehensive sign languages in the world” (Strickland, n.d.).

It wasn’t long ago that deaf students would not have been integrated into regular classes. It was just seven years ago in 2003 that Great Britain, a progressive Nation, finally recognized sign language as a valid language. We have learned that every citizen, no matter their impairment or ailment, has their place in society. Being deaf used to come with the stigma of worthlessness; thankfully this is no longer the case. Sign language has made such great strides that educators now see its merits in not only the education and communication with the deaf but with infant children as well. Infants and toddlers are being successfully taught basic signs that allow them to communicate with their parents before they develop oral communication skills. On a personal note, I can attest to the ability of children to learn how to sign. I for one am grateful for its creation!

References:

Berke, Jamie. (2010). Deaf history – history of sign language: how a language of gestures came to be. About.com: Deafness. Retrieved October 20, 2010. From http://deafness.about.com/cs/featurearticles/a/signhistory.htm

Fleming, Sandy. (2002). Deaf culture: history of american sign language. Essortment.com. Retrieved October 20, 2010. From http://www.essortment.com/hobbies/deafculturehis_slcm.htm

Savitt, Ari. (2007). Evolution of a language: American sign language. Lifeprint.com. Retrieved October 22, 2010. From http://www.lifeprint.com/asl101/pages-layout/evolutionofsignlanguage.htm

Strickland, Jonathan. (n.d). How sign language works. HowStuffWorks.com. Retrieved October 20, 2010. From: http://people.howstuffworks.com/sign-language2.htm

Charles-Micel de lÉpée. Wikipedia.org. Retrieved October 25, 2010. From http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles-Michel_de_l’Épée

How many different types of sign language are there? Answerbag.com. Retrieved October 25, 2010. From http://www.answerbag.com/q_view/500510

Sign Language. Wikipedia.org. Retrieved October 19, 2010. From http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sign_language

Hi Ryan,

Your video was really effective and I liked that you chose not to use any sound. I have a little girl in my class who has a cochlear implant that she recieved when she was 4. There is a lot of controversy about these devices with the hearing impaired and hearing communities. I taught her in Kindergarten and again this year in grade 2. It is amazing to see how far she has come in a few short years. She hears differently then you and I would and has to make sense of the sounds coming in – then when she goes to bed – she hears nothing. As you spoke about above, she learns through pictures and looks at the image of the whole world rather then segmenting the sounds – this is hard for her as the sounds she hears are different. She is a visual learner. It’s amazing what technology can do to support special needs students. She is able to do everything the others in my class can do – just in a different way.

On a personal note – it’s great to see that you are in this program! Where are you teaching this year? Jen is having another baby in February which is exciting. How is Toby?

Take care,

Alison