One of the significant milestones of human cultural development has been the creation of symbolic systems to represent and communicate thought. Writing systems based on this capability have allowed our species to externalize ideas, store them for future reference, and communicate with others irrespective of boundaries of time or space. The change from signs which directly related to the idea or object to signs which were purely symbolic had significant implications for education and social structure.

It is ironic that the development of symbolic writing systems led to illiteracy and the roots of inequality that persist into current society.

This entry will look at the definition of icon and symbol, symbolic mark-making in Mesoamerica in the Zapotec culture, and the implications of symbolic writing for social structure and education.

Icon, Index and Symbol

In the late 19th century, Charles Sanders Peirce described the terms ‘icon’, ‘index’ and ‘symbol’ in the context of communication.

“An Icon is a sign which refers to the Object that it denotes merely by virtue of characters of its own, and which it possesses, just the same, whether any such Object actually exists or not… A Symbol is a sign which refers to the Object that it denotes by virtue of a law, which operates to cause the Symbol to be interpreted as referring to that Object.” (Peirce in Buchler 1955, p.101).

The “law” governing the meaning of a symbol is arbitrary and agreed upon by a group. For example, a sign which is a drawing of a bull’s head might indicate a bull for trade, in which case the bull’s head would be an icon. If, however, the bull’s head were to represent something else entirely, like a sound, or a whole idea like strength, it would be termed a symbol.

Hard-Wired for Symbols?

Within the course of language development the technology of symbolic writing has developed at least four times. There is evidence for this in China (6500 BCE)(Hecht, 2003), Mesopotamia (fourth century BCE)(Barton, 2007), Egypt (3000 BCE) and in Mesoamerica (1000 BCE)(del Carmen Rodríguez Martínez et al., 2006). The fact that this occurred independently in geographically distinct parts of the world suggests that humans are somehow biologically predisposed to creating this kind of symbolic mark-making to record their thoughts or ideas.

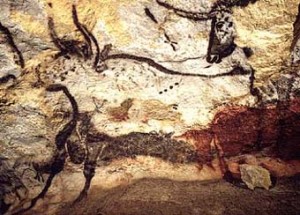

It could be argued that the cave paintings created by anatomically modern humans in the Upper Paleolithic period (c35,000 BCE) were the earliest icons, and were the beginning of a sequence which led to symbolic writing (Watkins, 2001). It may also be true that any kind of mark that represents something in the world of the mark-maker, be it a thought or an ear of corn, is symbolic. The mark is two dimensional, or at best slightly three-dimensional in the case of marks on clay or stone, and this is already an abstraction. It is beyond the scope of this entry to debate the biological basis for mark-making in humans, but the evidence for our being hard-wired to create written works is quite compelling.

Writing in Mesoamerica – Zapotec Signs and Symbols

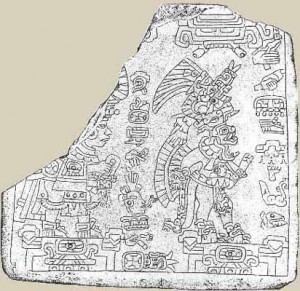

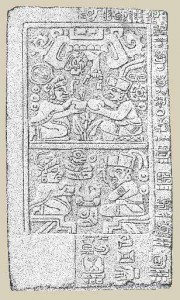

By 600 BCE, the Zapotec of Mesoamerica had a mixed system of writing, which included both icons and symbols (Urcid, 2005). They had a central capital city at Monte Alban, which remained the centre of the Zapotec empire for over a thousand years (Marcus, 1980). Elements of Zapotec script persisted for almost 1500 years (Urcid, 2005). The great difficulty researchers have had in deciphering the Zapotec script is a reflection of the fact that it is at least a partially symbolic system. If it were purely iconic, there would be little difficulty in understanding the marks.

Symbolic writing appears to have existed in Mesoamerica since c1000 BCE. A recent discovery of Olmec writing on stone monuments pushes the date of symbolic writing in the region to the first millennium BCE (del Carmen Rodríguez Martínez et al., 2006). Earlier instances of writing on more ephemeral surfaces (wood or bark) have disintegrated in the tropical climate of Mexico, so there are probably holes in the archaeological record of writing in Mesoamerica (Marcus, 1980).

In the same time period as the development of written symbolic script, Zapotec society moved from small chiefdoms to a more centralized concentration of power in the Oaxaca valley (Marcus, 1999). Haviland, et al (2008) see writing as an indicator of centralized power. “With writing, central authorities could disseminate information and store, systematize, and deploy memory for political, religious and economic purposes.” (p.253).

Zapotec, like much of early Mesoamerican writing, was political. Mesoamerican rulers recorded conquests, dynastic marriages and named themselves after the calendrical titles they were born under. They also associated themselves with major astronomical events. “Different though this may be from the record keeping of ancient Mesopotamia, all writing systems share a concern with political power and its maintenance.” Haviland et al. (2008), p.254

In a society that practiced ancestor worship, establishing links of genealogy was important in legitimizing rulers. Script was used as part of monuments, and on tombs, to demonstrate how powerful and legitimate the rule of a particular person or lineage was. (Urcid, 2005; Marcus, 1980)

“The main thesis guiding the exegesis of scribal practices in elite domestic contexts is that, in a highly ranked and unequal society, the transfer of property between human generations is central to the reconfiguration or reproduction of the social system, and that ancestor veneration, particularly among the higher-ranking corporate groups, constituted a cultural institution deployed in order to legitimize such transferences.“(Urcid, 2005, p.28)

Implications

While it is impossible to definitively say that writing caused centralized power in Mesoamerica, or that centralized power caused symbolic writing, it is true that the creation of both of these technologies (the art of centralized governance could probably be described as a technology) was contemporaneous (Marcus, 1999). An undeniable result of a move to symbolic writing would be that there would be elite who could read and write the script while the bulk of the population remained illiterate.

If a written sign is an icon, a direct representation of the thing it signifies, it is easily understood by anyone. If an ear of corn represents an ear of corn then any member of society can read the mark. If, however, an ear of corn represents something else, say fertility, then only those who know the arbitrary link between corn and fertility will be able to correctly interpret the sign.

Once a culture begins to have signs that require specialized knowledge to create and interpret they begin to create in-groups and out groups, those who have the knowledge and those who don’t.

From the Merriam Webster Online Dictionary:

in–group noun \ˈin-ˌgrüp\

Definition of IN-GROUP

1: a group with which one feels a sense of solidarity or community of interest

out–group noun \ˈau̇t-ˌgrüp\

Definition of OUT-GROUP

: a group that is distinct from one's own and so usually an object of hostility or dislike

In Zapotec culture, the in-groups now consisted of the ruling elite, the scribes they paid and a new class of priests. Even ancestor worship changed from where a person’s direct ancestors were venerated to worship of the ancestors of the ruling elite. (Marcus, 1999)

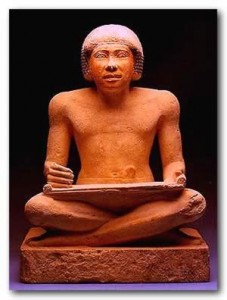

Having specialized writers, readers and patrons creates a stratification of social structure. Houston (2004 ) describes the creation of “script communities”, the in-groups that write, read and teach symbol systems. There must be enough resources in the community that the scribes, teachers and learners can take the time away from subsistence activities to take part in the act of writing. The community must value the work of scribes enough to feed them, although they may not participate in farming or hunting. With unequal access to the technology the distribution of power will necessarily change. The most important people may no longer be hunters or farmers.

Symbolic systems create the need for education in which the novice is taught and must memorize the meaning of a sign, and be able to reproduce it faithfully in order for the written piece to be understood by others. Houston (2004) sees this as implying levels of social status, gender relations, and power based on who gets to read and write and how the technology is taught. Education in writing and reading was an activity removed from the teaching of skills needed for subsistence. “Ensuring that a script endures must involve the strategies of pedagogy and apprenticeship.” (Houston, 2004, p.6). It created a class of experts who were not directly involved in the production of food or the defence of the society against enemies.

The development of symbolic writing led to the concept of illiteracy, which continues to underpin inequalities and access to power in contemporary human society.

References

Barton, D. (2007). Literacy: An introduction to the ecology of written language – 2nd Ed. Blackwell Publishing, Hong Kong. Retrieved October 29, 2010 from http://books.google.com/books?id=4ZjfJ8cPe1UC&pg=PA111&lpg=PA111&dq=historical+change+to+symbolic+writing&source=bl&ots=33WOWubewS&sig=2HTI4e1pQElBHGX1YWqC1SLXy30&hl=en&ei=T9W0TJ3MFcOB8ga-wYCGCg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=8&ved=0CDUQ6AEwBw#v=onepage&q=historical%20change%20to%20symbolic%20writing&f=false

Buchler, J. (1955). Philosophical Writings of Peirce. Dover, New York. Retrieved October 4, 2010 from http://books.google.ca/books?id=ClSjXRIbxAMC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Philosophical+Writings+of+Peirce,+ed.+Justus+Buchler&source=bl&ots=a9tGkq1FKE&sig=4nymk-iHyi2kh4ZIdsdbiE_dwMw&hl=en&ei=cZHNTM6jNojUngfE8fX2Dw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CB#v=onepage&q&f=false

del Carmen Rodríguez Martínez, M., Ceballos, P. O., Coe, M.D., Diehl, R.A., Houston, S.D., Taube, K.A. & Calderon, A.D., (2006). Oldest Writing in the New World. Science. 313(5793), pp. 1610 – 1614. DOI: 10.1126/science.1131492

Haviland, W.A., Prins, H.E., Walrath, D. & McBride, B. (2008). Evolution and prehistory: the human challenge – 2nd Ed. Thompson, USA. Retrieved October 13, 2010 from http://books.google.com/books?id=LfYirloa_rUC&pg=PA254&lpg=PA254&dq=prehistoric+mesoamerican+writing&source=bl&ots=gevad034Y_&sig=03-l87aJjdxIkOKPCvLsQnim1gE&hl=en&ei=6ZzMTL2fAY-gsQOJwOzsDg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CBgQ6AEwADgK#v=onepage&q&f=false

Hecht, J. (2003). Oldest known Chinese script discovered. New Scientist.com. Retrieved October 28, 2010 from http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg17823931.600-oldest-known-chinese-script-discovered.html

Houston, S.D. (2004). The first writing: script invention as history and process. Cambridge University Press, UK. Retrieved October 25, 2010 from http://books.google.ca/books?id=jsWL_XJt-dMC&printsec=frontcover&dq=First+Writing:%EF%BF%BC+Script+Invention+as+History+and+Process&source=bl&ots=DbtYs5GeZJ&sig=miWcr6tBUCkYdFqW9BCYlD3Sxbo&hl=en&ei=kqP%EF%BF%BCMTJCrIZT0tgOhu6nuDg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CCcQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q&f=false

Marcus, J. (1980). Zapotec Writing. Scientific American 242, pp. 50 – 64.

doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0280-50

Marcus, J. (1999). Men’s and Women’s Ritual in Formative Oaxaca. In Social Patterns in Pre-Classic Mesoamerica, David C. Grove and Rosemary A. Joyce, Eds. Dumbarton Oaks, USA. Retrived October 26, 2010 from http://www.doaks.org/publications/doaks_online_publications/Social/social04.pdf

Urcid, J. (2005). Zapotec Writing: Knowledge, Power and Memory in Ancient Oaxaca. Retrieved October 10, 2010 from http://www.famsi.org/zapotecwriting/zapotec_text.pdf

Watkins, T. (2001). Signs Without Words: The Prehistory of Writing. Paper read in London, UK. December 15, 2001. Retrieved October 17, 2010 from http://www.arcl.ed.ac.uk/arch/watkins/watkins_signs.html