Image Source: http://www.brighttomato.com.au/learning-to-read-sight-words-56-sets-of-picture-word-cards-preschool.html

I chose this picture because I feel games like these are vital to the process of moving from orality to literacy.

Two nights ago my wife and I were discussing a difference in our opinions – I can’t remember exactly what it was we were arguing about. However, I do remember commenting that I didn’t know how I could possibly see her side of the story because where she was coming from was completely foreign to me. How could I see her point of view if I had no way to relate to it? This is how I felt as I started to read Orality and Literacy. Oral cultures, too, seemed foreign to me. I have been so immersed in what I believed to be a culture based on literacy that I never stopped to give it much thought. Previously, I would have also bet that Oral based cultures no longer existed in the year 2010; I now know I am wrong. It wasn’t until I neared the end of Chapter 3 did it start to “click”. And what exactly was that epifony?

“The same mnemonic or poetic economy enforces itself still where oral settings persist in literature cultures, as in the telling of fairy stories to children: the overpoweringly innocent Little Red Riding Hood, the unfathomably wicked wolf, the incredibly tall beanstalk that Jack has to climb” (Ong, 69).

Ong’s book, Orality and Literacy, discusses how mankind has evolved from an oral culture to one of literacy. What I have come to realize is that each and everyone us experience that kind of evolution in our own lives.

I have two young daughters. Looking back on the developmental stages they have experienced thus far in their lives I have realized that they live in almost a purely oral culture (my eldest is just learning to read). Written words have no meaning or value in their world. Spoken words, songs, shapes, colours, images, however, do. If I was to leave them a note asking them to clean-up their rooms they would look at the paper and most likely get out their crayons and draw on it. But, if I asked them to clean-up their rooms they would be able to understand my spoken words and do what I asked.

What I have also found interesting is just how one moves from orality to literacy. Using my daughter again as an example, I have been able to witness first-hand how she is learning to read. I was surprised to learn that for hersounding words out isn’t as effective as memorization of letters. Ong states that “colourless personalities cannot survive oral mnemonics” (69). In the case of my daughter this could not be more true. She can read complicated words such as, “magnificent, beautiful, and fantastic” with little problem because these words are part of her favourite stories and she has learned them through repetition and memorization. She never learned to sound these words out but through listening (and watching) she was able to associate the letters ‘m-a-g-n-i-f-i-c-e-n-t’ to mean just that. These words hold some value to her (again because they are part of her special books) and common words such as “that, some, and there” give her problems because they aren’t ‘special’ words.

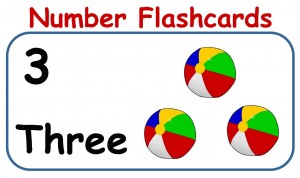

What I also find fascinating about my daughters’ oral culture is just how much visual and auditory cues make a difference in their understanding (or at least in their ability to recall information). Take the following flashcard as an example.

Source: http://www.magnaplay.com/Free_Activities.html

By itself they wouldn’t know that ‘T-H-R-E-E’ spells three but seeing it in context with the number 3 and next to three balls that they could count will allow them to memorize those letters (in that arrangement) to mean ‘three’. “A textual, visual representation of a word is not a real word, but a ‘secondary modeling system’” (Ong, 74).

In an article by Levin, Bevin and Lesgold (1976) they claim that “children (typically, prereaders just entering school) recalled substantially more about a passage when the passage was accompanied by pictures than when it was presented alone” (368). I have also experienced this when my daughter gets stuck on a word while reading. The first thing she does it look at the pictures on the page. Most times, the pictures will give her the visual cue she needs to recall the word from memory. However, when that doesn’t work she is forced to sound it out (although begrudgingly).

A child’s pre-literate culture is not isolated to just visual learning instances. Song is another example that proves learning can take place without any literal references. I am constantly amazed at the words my daughter is able recall through listening to song (even if she couldn’t read them on a piece of paper). What I find particularly interesting is that the words of the song alone she cannot remember. However, put it to music and she can recall the entire song word-for-word without missing or mispronouncing a single one.

When we were born we came into the world void of speech and the ability to be understood (or understand others). Talking to an infant through “emotionless” conversation would serve little purpose. Yet, expressiveness, tone and gestures are well received by those unable to formulate the words. For most, if not all of us, our learning has stemmed from tactile, oral and visual experiences. We were given visual and auditory cues and through repetition and memorization we were able to formulate words; we were able to change the spoken word into its written form. But, it is important to recognize the difference between oral and written language. Oral language develops naturally (stemming from one’s daily existence) whereas written language is developed through teachings of vocabulary and sentence structure (Hill, 4). What this chapter has taught me is that before I graduated into a society of literacy I first had to navigate through my infant stages of orality.

References:

Hill, Susan. (2010) Oral language play and learning. Practically Primary. FindArticles.com. Retrieved September 27, 2010 from: http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_6953/is_2_15/ai_n54035431/

Levin, J.R., Bender, B.G., Lesgold, A.M. (1976). Pictures, Repetition, and Young Children’s Oral Prose Learning.AV Communication Review, Vol. 24, No. 4 (Winter, 1976), pp. 367-380. Retrieved September 27, 2010 from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/30217901.pdf?acceptTC=true

Ong, Walter. (1982) Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. London: Methuen.

Commentary #1: Oral Cultures are Everywhere

Commentary #1

ETEC 540

Ryan Edgar

Commentary #1: Oral Cultures are Everywhere

I chose this picture because I feel games like these are vital to the process of moving from orality to literacy.

Two nights ago my wife and I were discussing a difference in our opinions – I can’t remember exactly what it was we were arguing about. However, I do remember commenting that I didn’t know how I could possibly see her side of the story because where she was coming from was completely foreign to me. How could I see her point of view if I had no way to relate to it? This is how I felt as I started to read Orality and Literacy. Oral cultures, too, seemed foreign to me. I have been so immersed in what I believed to be a culture based on literacy that I never stopped to give it much thought. Previously, I would have also bet that Oral based cultures no longer existed in the year 2010; I now know I am wrong. It wasn’t until I neared the end of Chapter 3 did it start to “click”. And what exactly was that epifony?

“The same mnemonic or poetic economy enforces itself still where oral settings persist in literature cultures, as in the telling of fairy stories to children: the overpoweringly innocent Little Red Riding Hood, the unfathomably wicked wolf, the incredibly tall beanstalk that Jack has to climb” (Ong, 69).

Ong’s book, Orality and Literacy, discusses how mankind has evolved from an oral culture to one of literacy. What I have come to realize is that each and everyone us experience that kind of evolution in our own lives.

I have two young daughters. Looking back on the developmental stages they have experienced thus far in their lives I have realized that they live in almost a purely oral culture (my eldest is just learning to read). Written words have no meaning or value in their world. Spoken words, songs, shapes, colours, images, however, do. If I was to leave them a note asking them to clean-up their rooms they would look at the paper and most likely get out their crayons and draw on it. But, if I asked them to clean-up their rooms they would be able to understand my spoken words and do what I asked.

What I have also found interesting is just how one moves from orality to literacy. Using my daughter again as an example, I have been able to witness first-hand how she is learning to read. I was surprised to learn that for hersounding words out isn’t as effective as memorization of letters. Ong states that “colourless personalities cannot survive oral mnemonics” (69). In the case of my daughter this could not be more true. She can read complicated words such as, “magnificent, beautiful, and fantastic” with little problem because these words are part of her favourite stories and she has learned them through repetition and memorization. She never learned to sound these words out but through listening (and watching) she was able to associate the letters ‘m-a-g-n-i-f-i-c-e-n-t’ to mean just that. These words hold some value to her (again because they are part of her special books) and common words such as “that, some, and there” give her problems because they aren’t ‘special’ words.

What I also find fascinating about my daughters’ oral culture is just how much visual and auditory cues make a difference in their understanding (or at least in their ability to recall information). Take the following flashcard as an example.

By itself they wouldn’t know that ‘T-H-R-E-E’ spells three but seeing it in context with the number 3 and next to three balls that they could count will allow them to memorize those letters (in that arrangement) to mean ‘three’. “A textual, visual representation of a word is not a real word, but a ‘secondary modeling system’” (Ong, 74).

In an article by Levin, Bevin and Lesgold (1976) they claim that “children (typically, prereaders just entering school) recalled substantially more about a passage when the passage was accompanied by pictures than when it was presented alone” (368). I have also experienced this when my daughter gets stuck on a word while reading. The first thing she does it look at the pictures on the page. Most times, the pictures will give her the visual cue she needs to recall the word from memory. However, when that doesn’t work she is forced to sound it out (although begrudgingly).

A child’s pre-literate culture is not isolated to just visual learning instances. Song is another example that proves learning can take place without any literal references. I am constantly amazed at the words my daughter is able recall through listening to song (even if she couldn’t read them on a piece of paper). What I find particularly interesting is that the words of the song alone she cannot remember. However, put it to music and she can recall the entire song word-for-word without missing or mispronouncing a single one.

When we were born we came into the world void of speech and the ability to be understood (or understand others). Talking to an infant through “emotionless” conversation would serve little purpose. Yet, expressiveness, tone and gestures are well received by those unable to formulate the words. For most, if not all of us, our learning has stemmed from tactile, oral and visual experiences. We were given visual and auditory cues and through repetition and memorization we were able to formulate words; we were able to change the spoken word into its written form. But, it is important to recognize the difference between oral and written language. Oral language develops naturally (stemming from one’s daily existence) whereas written language is developed through teachings of vocabulary and sentence structure (Hill, 4). What this chapter has taught me is that before I graduated into a society of literacy I first had to navigate through my infant stages of orality.

References:

Hill, Susan. (2010) Oral language play and learning. Practically Primary. FindArticles.com. Retrieved September 27, 2010 from: http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_6953/is_2_15/ai_n54035431/

Levin, J.R., Bender, B.G., Lesgold, A.M. (1976). Pictures, Repetition, and Young Children’s Oral Prose Learning.AV Communication Review, Vol. 24, No. 4 (Winter, 1976), pp. 367-380. Retrieved September 27, 2010 from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/30217901.pdf?acceptTC=true

Ong, Walter. (1982) Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. London: Methuen.