Using the LfU literature as a lens, I reflected on the “Back Country Bridge” project that my STEM 11/12 class did this past September. At the time, I had never heard of Learning For Use as a design theory. This is what we presented to the students on the first day:

“Research, design, and construct the lightest possible wood-frame bridge that will safely allow a 100 kg person to cross a 4.0 m crevasse.”

Students worked collaboratively in groups of three. Evaluations were set as 50% for the final bridge performance, 25% for written tests, and 25% for shop procedures. There was some direct instruction on how to shape and fasten wooden members, how to analyze forces, and how to test for strength. We assigned homework problem sets with relevant math and physics, and set a “prototype” testing day at the 2.5 week mark to keep the students from procrastinating. The entire project was 4.5 weeks long.

In retrospect, here is how I think we faired relative to my paraphrasing of the four LfU tenets of design found in Edelson (2000, p. 375):

1. Learning takes place through construction and modification of knowledge structures.

This is later defined as constructivism, and I think we are following a constructivist model of learning. We are quite purposeful in our attempt to ensure that projects end with the creation of an artifact, be that physical or digital. The students really got into building and testing the bridges, so that seemed like a success.

2. Learning can only be initiated by the learner, whether it is through conscious goal-setting or as a natural, unconscious result of experience.

I feel that this is really about authentic engagement. Later in the paper, it clarifies:

“…although a teacher can create a demand for knowledge by creating an exam that requires students to recite a certain body of knowledge, that would not constitute a natural use of the knowledge for the purposes of creating an intrinsic motivation to learn” (Edelson, 2000, p.375)

I like that he emphasizes that “academic threats” or extrinsic motivation are not authentic engagement. I think we failed here in our bridge project. Although many of the students got into the building and testing, we spent zero time considering if this project was relevant to students or how they experience their environment. I chose the project because I do back-country travel, and I like bridges. In other words, it was relevant to me. In future, I would like to be more considered in our choice of projects, or find some way to involve students in the selection process.

3. Knowledge is retrieved based on contextual cues, or “indices”.

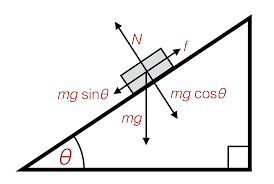

This is called situated learning elsewhere in the literature (NLG, 1996). For those of you who teach physics and mathematics, you’ll know that the analysis of bridge structures is about as situated as trigonometry and “static equilibrium” can get. We did test to see if students could recognize contextual cues and transfer this knowledge to similar structures, like bicycle frames and chairs. The results were so-so, and we discussed that as colleagues. Perhaps we need to include more transfer exercises or reflections that ask students to place bridge analysis in a larger context, something Garcia & Morrell (2013) call “Guided Reflexivity”, and Gee (2007) calls “Critical Learning”. We didn’t do much in the way of meta-cognition at that point in the year.

4. To apply declarative knowledge, an individual must have procedural knowledge.

I had trouble with this tenet. Isn’t this isn’t just a repeat of principle 1? Since our students are working in groups in a constructivist model, the development of common vocabulary and declarative knowledge is fully necessary to communicate, or the project doesn’t move forward (which sometimes happens and requires intervention). The act of design and successful iteration is the application of “procedural knowledge”, which has declarative knowledge embedded. Maybe I’m missing something here.

Overall, I feel like LfU is just a merger of constructivism and basic cognitive learning theories. My school’s program and projects would benefit a lot by being more purposeful about authentic engagement and helping students see their project as part of a larger domain of related problems.

Edelson, D.C. (2001). Learning-for-use: A framework for the design of technology-supported inquiry activities. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 38(3), 355-385

Garcia, A. & Morrell, E. (2013). City Youth and the Pedagogy of Participatory Media. Learning, Media and Technology 38(2). 123-127. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2013.782040

Gee, J. 2007. Semiotic Domains: Is playing video games a “waste of time?” In What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy (pp.17-45). New York: Palgrave and Macmillian.

New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review. 66(1), 60-92.