Fightingcc licensed photo shared by Anke L

I did my best to unplug over the holidays, so there has been lots to catch up on… It’s hard not to be struck by the sheer volume and passion of responses stirred up by George Siemens’ post Open isn’t so open anymore. It’s a long, multi-pronged argument, so a single excerpt won’t do it justice, but…

Do we need greater formalization and promotion of openness within education? Or will openness as an ideology have little or no traction outside of a small group of marginal fanatics?

The uncertainty on how to organize ourselves is precisely what has caused openness to veer to the pragmatic. Why spend days, even months, debating seemingly insignificant details of openness? Why not just produce something and share it in any manner you wish? Why not just let openness evolve as it is?

Robert Hutchins has stated that “the death of democracy is not likely to be an assassination from ambush. It will be a slow extinction from apathy, indifference and undernourishment”. A similar concern exists for openness in education.

Something about this tension between ideology and pragmatism clearly resonates with people, as illustrated by the many comments on George’s post itself, and the many responses out in the blogosphere, a few of which I sample below. Again, I worry my selections do an injustice to the authors, but frankly the notion of stringing the many labyrinthine arguments into a coherent synthesis feels a little daunting:

David Wiley: “I’m not sure why George makes the leap from my more nuanced view of openness to my somehow not believing that openness is an ideological concept. Of course openness is a concept – and of course people are ideological about it’s meaning. But, like democracy, little concrete debate can be had about the concept (and no implementation of the concept can occur) until it has been operationalized. How can you debate a concept without a concrete proposal as to it’s meaning?”

Jim Groom: “The larger question in my mind is that what’s under girding this discussion is an even more insidious logic than a denatured sense of open, and that’s a sense of entitled leadership. Fact is, the push to make sense of open as a term and discuss it’s meaning, future shape, and ultimate value seems to be the most definitive step in forming an institutional structure of power around it. Who gets to discuss what open is? Where do they do it? Companies don’t really care too much about that discussion, they just care about appealing to users through a term, and if they make up the table, along with administrators at universities and the like, then why do we need to go to the table at all? Isn’t the push away from these legacies of power and privilege a part of what open is working against on it’s most powerful and truly transformative levels? Why does their need to be a continental congress on open? Why do we have to conflate it with system and then elect officials to define it for us? Part of the power and the hope of this space for me is a new scale of working though these ideas that’s both hyper-individual and communally local at the same time.”

Graham Atwell has initiated a series of posts inspired by the ongoing dialogue: “if Open Education is to mean anything, it has to address the question of social divisions including class, gender and race. I am unconvinced this can be done from inside the existing educational institutions, although of course is will need the support of those working in those organisations. Instead I think we need to use the power of the internet to provide opportunities for education and learning outside the present system and to embed those learning activities in wider communities than the present institutions address.”

And Martin Weller: “I can live with a plurality of definitions. In fact, I rather like it, and I think academic obsession with finding a precise definition often gets in the way of being productive – witness how every paper, conference presentation, or website about learning objects had a definition of what a learning object was, instead of getting on with just sharing stuff.”

If this line of argument interests you, I’d also recommend checking out Frances Bell, Judy Breck, Jeremy Browne, Mike Caulfield, and this characteristically irreverent take from the CogDog. And although Tannis Morgan’s Looking backward to look forward has a wider scope, and is not explicitly responding to this hubbub, I highly recommend giving it a read in this context: “I’m increasingly aware that I have a responsibility to step outside of the ed-tech echo chamber that I participate in, and spend more time looking for a different type of conversation. This requires looking backward and beyond. By looking backward, I continue to find relevance in some of Mackey’s geolinguistic observations of the 80s and 90s; commonalities between the self-directed learning movements of the 70s and later and the desire for substantial change in teaching and learning in higher education.”

Now, all of the people I just linked to are thinkers I hold in great esteem, and in many cases I’m blessed to think of them as friends as well. So I am not inclined to dismiss a subject that clearly inspires such intensity of thought and expression. That said, I cannot help but feel like this is a debate that is a little… well, academic. For one thing, I personally don’t have any problem holding considerations of ideology and pragmatism within the same movement. I think it says something that I find myself agreeing with almost everything that all of these ostensible opponents are writing. For one thing (as Chris Lott notes) they are hardly mutually exclusive. And every social and political movement I can think of harbours a tension between the true believers and those who want to get things done someway, somehow… And every movement that has ever amounted to anything has had both types of people among its ranks.

And reading all this stuff, I find myself thinking about most often about Great expectations for e-learning in 2010 from Tony Bates:

In many countries, 2010 will be a difficult year financially. Governments are going to have to take control of their large deficits, and their options are limited: cut expenditure, increase taxes, borrow more money. But you won’t be able to borrow more money to pay off the old because it will be too expensive, and who is going into an election with a promise of more taxes? With a majority of the electorate becoming seniors (well, almost), you can’t cut health budgets. So we’ll have to cut the universities (after the civil service and the wages of elected officials, of course). See, that decision wasn’t so difficult after all, was it?

The USA and Britain in particular face some very difficult financial decisions over the next few years (and I believe 2011 will be worse than 2010 for public sector cuts, so it won’t be a question of trying to ride out things until the situation improves – it could be a long and increasingly bumpy ride).

…but every challenge is also an opportunity, and the increasingly dire state of public financing does offer a real opportunity to re-think current teaching and learning environments in ways that will not only help control costs but also produce the learning needed in the 21st century.

So, especially if you are not working in a privileged first-tier research university, brush off your revolutionary plans for e-learning (no, NOT clickers) and have them ready for your sorely pressed administration in 2010. It would also help if you could show how this could save some money as well, but that might be another challenge.

Looking past the reality that many of us who engage in these arguments from positions of relative comfort may not have jobs in a year or so…

I am not alone in thinking that the practical benefits of well-planned open practice across the academy could realize significant cost savings and increased benefits to the public that ultimately is footing the bill. So seeing such bright minds putting so much energy into issues of revolutionary ideological purity has me wishing similar activity was dedicated toward developing revolutionary plans, articulating strategies that will not only seem worth trying but also have reasonable prospects of success. (To be fair, I think George proposes work that might prove useful in this regards in his post Measurement of Openness in Education Systems.) If we don’t have our collective act together in this regard, the most likely outcome of budget cuts just might be retrenchment and even reactionary practice in the name of austerity.

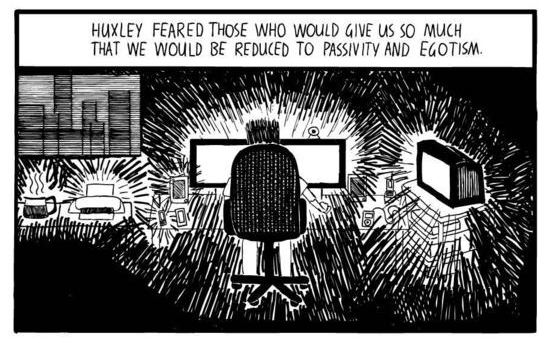

Beyond the grim economic realities that almost everyone on this planet will struggle against in the coming years, I see a number of other trends that strike me as far more threatening to the shared values of self-described open educators (and diverse as the movement is, I do think there are shared values, however broad) than what open really means. Over the next week or so, I intend to write about a few of these threats… Like the profoundly undemocratic process that is working to establish a shockingly awful global copyright scheme… I’ve also been brooding about the diminishment of the qualities that made Web 2.0 so genuinely interesting and innovative (I’m thinking of what Jonathan Zittrain describes as the generative web), endangered by the return of corporate-driven platform-based computing (hello mobile web) and a disturbingly passive and self-absorbed online culture. Then there is the rise of digital sweatshops and content farms, which will both threaten and demand a response from a global intellectual culture. I don’t know what I will say about the absence of a meaningful critical thinking apparatus in mass public discourse, but I may risk a rant or two along those lines…

So in both my response to the debate on the rigorous definition of openness, and on what the ‘real’ threats are… what am I missing?