This post is the latest in my annual series where I publically commit to share the evidence-based change I’m making to my teaching practice this year. (See last year’s post, where I shared rationale and resources on two-stage exams, which were awesome.)

What’s the idea?

A Student Management Team (SMT) is a small group of students (usually 3-5) that meets regularly throughout a course, and whose primary objective is to facilitate communication between the course instructor and the class. I first learned about SMTs at the Teaching Preconference at SPSP this past February, from a talk given by Jordan Troisi. He uses them to gather feedback on what’s working well and what isn’t, to gather ideas about potential changes, and sometimes to explain in detail why something can’t be changed. The SMT also creates, administers, and analyzes mid-course feedback, which springboards dialogue with the instructor. Overall, the SMT acts as a communication bridge between the rest of the class and the instructor.

Why am I interested?

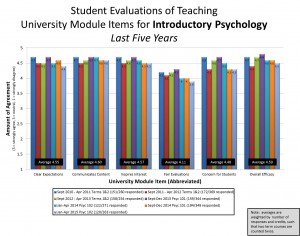

Every major change I’ve made to my courses in the past 3-4 years has (a) increased the amount of peer-to-peer learning/interaction, and (b) implemented an evidence-based practice (see the impact of these on my teaching philosophy revision, here and here). Of all my courses, I think my introductory psychology courses (101 and 102) need the most attention. I see SMTs as an opportunity to work with motivated students to help me identify what changes are most needed and how we can implement them on a large scale.

Although most students rate these courses positively overall, I know that some of my 370 students (each term) feel overwhelmed, lost, stressed, and alone. To help somewhat, I have held a weekly Invitational Office Hour outside the classroom on Friday afternoons, and I have happily met many of my students face-to-face during that period. Some longstanding friendships among student attendees have even developed at those office hours! But I continue to struggle with the sheer size of my classes. How can I connect more students with each other more intentionally? How do I integrate more meaningful peer-to-peer interaction to help students learn while building community? I’m interested in hearing feedback from the SMT on these and other issues. I am also looking forward to building ongoing working relationships with a small cohort of students. My position is such that I don’t get many opportunities to mentor students (unlike, say, if I was running a research lab), so I’m excited by the idea of working closely with a few students to help me communicate with the many.

What evidence is there to support it?

Not as much as I’d ideally like to see, but as Jordan notes in his papers, it’s relatively new. I see no downsides to trying it at this point, and Jordan’s data suggest benefits not just to SMT members (Troisi, 2014), but also to the whole class (Troisi, 2015). I’m interested in adding a measure of relatedness, and seeing if his findings for autonomy hold with a class almost 15x larger (with, perhaps, 15x the need?).

Troisi, J. D. (2015). Student Management Teams increase college students’ feelings of autonomy in the classroom. College Teaching, 63, 83-89.

- Shows that students enrolled in a course that had an SMT increased their sense of autonomy by the end of the course, but students in the same course (same instructor, same semester) without an SMT showed no change in their autonomy. In other words, students feel more in control of their outcomes if they have an SMT as a conduit (not just if they’re actually in the SMT). This paper uses the lens of Self Determination Theory (a major theory of motivation), and provides a nice introduction for non-psychologists who might be interested in using it to inform their teaching practice. (In a nutshell: highest motivation for tasks that meet competence, autonomy, and relatedness needs.)

Troisi, J. D. (2014). Making the grade and staying engaged: The influence of Student Management Teams on student classroom outcomes. Teaching of Psychology, 41, 99-103.

- Shows benefits for the SMT members themselves. They perform better in the course than non-members (after controlling for incoming GPA), which seems partly due to increased engagement over the duration of the course.

Handelsman, M. M. (2012). Course evaluation for fun and profit: Student management teams. In J. Holmes, S. C. Baker, & J. R. Stowell (Eds.), Essays from e-xcellence in teaching, 11, 8–11. Retrieved from the Society for the Teaching of Psychology website: http://teachpsych.org/ebooks/eit2011/index.php

- Anecdotal discussion of benefits, with description of how he has implemented it.

- Free e-book!

Are you thinking of trying out SMTs? Let’s talk! Email me at cdrawn@psych.ubc.ca

Follow

Follow