Thank you to each of my students who took the time to complete a student evaluation of teaching this year. I value hearing from each of you, and every year your feedback helps me to become a better teacher. As I explained here, I’m writing reflections on the qualitative and quantitative feedback I received from each of my courses.

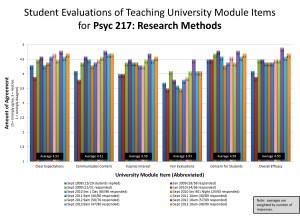

Of all the courses I teach to learners, Research Methods is my oldest. Over the past 7 years I have taught 12 groups of learners (N = 846)! The core design has largely stayed the same, but I have made many changes on the basis of my own reflections, my adapting knowledge of the topic and our discipline, and—crucially—feedback from students. Quantitative feedback from the student evaluations has remained high this year (see the graph below for a comparison across years).

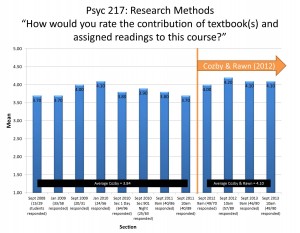

Now that I have used my own textbook for two years, I was able to explore quantitative ratings on the item “How would you rate the contribution of textbook(s) and assigned readings to this course?” As noted in the graph below, there seems to be a small shift favouring Cozby & Rawn, Canadian Edition (M=4.10 across four sections), over Cozby’s older editions (M=3.84 across 8 sections). Is the textbook perceived a bit more positively because it’s a better book or because I’m both an author and the course instructor? To this point, a few students made comments like this: “I really liked that you were the author of the textbook, it helped connect the course to the reading.” This kind of comment makes me wonder if my colleagues’ data show this shift as well. (I need a control series design rather than just an interrupted time series!)

The CozbyRawn textbook is the core text for this course, but I’ve always supplemented the nuts-and-bolts style book with secondary readings. Up until last year, all secondary readings were from the Stanovich text, but they had repeatedly been received poorly by students (see last year’s reflection). This year, I replaced most Stanovich readings with a few articles highlighting major issues being hotly discussed in our field (e.g., replication). Student feedback about this change was quite positive. Some students noted how the new topics/readings helped them understand current issues in the field, whereas others appreciated fewer readings overall and fewer Stanovich ones. I also experienced the change as a productive and helpful one that improved the course. Thanks to past years’ student feedback for triggering that change!

When I step back and look at the overall set of comments, there are some topics mentioned repeatedly. The one criticism that emerged was the midterms: a number of people found them too long and/or difficult. Because the class averages are in the range required by our department, the exam difficulty seems commensurate with student learning in my course. There were also some requests for a study guide, which is interesting because one does exist. I can’t vouch for the quality of it, but it’s available: http://highered.mcgraw-hill.com/sites/0071056734/student_view0/index.html I’ll make a note to advertise its existence in the syllabus. On the positive side, students found my enthusiasm and approach helpful, including sharing my past mistakes and communicating clear goals/learning objectives. Here’s a comment that sums up some of these themes:

“Who knew research methods could be so interesting? Lectures were consistently energetic and engaging and always promoted critical thinking. I really love that you incorporated contemporary issues in the psychology field into the course content – it has been very useful in interpreting content outside of this class. Continue to do that! Thanks for a great class!”

For next year, I’d like to strive to lecture less and have more in-class activities where people are using the material. I use active learning techniques frequently, but there are some topics that could benefit from revision (quasi-experiments comes to mind). I also intend to revisit the supplementary readings, see if I can replace the few remaining Stanovich chapters with articles available online, and update the “current” readings with ones published since last year (e.g., drawing from an even more recent Perspectives on Psychological Science issue). I’m also working on some bigger things that would span all sections, like adding a big data collection evening, and publishing all the abstracts in some form for next year’s students to be able to refer to.

Follow

Follow