As I mentioned in this previous post, I am working through feedback from my students. All quantitative data, as well as links to all previous blog posts (since 2011), are available here.

Last round I focused on PSYC 218 Statistics. For this installment, I focus on PSYC 417 Advanced Seminar in Applied Psychology of Teaching and Learning, which will be transitioning to the new course code PSYC 427 for my W2021 Term 2. The first time I taught this course, 10 students journeyed with me in May-June 2019. That pilot syllabus, an overview of the course, and reflections from that year, and my August 2019 (!) draft of Summer 2020’s syllabus are available here. By the time Summer 2020 actually occurred, we were well into the heart of the pandemic. Sixteen brave students joined me from around the world in July-August 2020 as we figured out how to teach and learn online. Here’s how I adapted the syllabus. Notably, both these first two offerings were during the summer and therefore were condensed into 6 weeks. Next time I offer the course (likely my last offering for at least a while), it will be stretched to a regular term.

I had never taught students entirely online before, and don’t have a ton of experience with upper level seminars. I tried my best to apply the Guiding c Principles when redesigning the course, particularly when it came to compassion and options and flexible deadlines. If you compare the Policies sections from my three pandemic courses in three successive terms, you can see the progression I made in articulating and embracing options and flexibility: PSYC 417 (Summer 2020), PSYC 217 (W2020 T1), and PSYC 218 (W2020 T2).

To be honest I don’t remember too many details about how I went about adapting the course. It was such a frightening and overwhelming flurry. I do recall that it’s when I came up with a weekly organizer and intensive module structure in Canvas, which I went on to elaborate in subsequent courses because it kept my organized. I left some notes to myself that I want to capture here:

- The students collaboratively made an excellent participation rubric. I still found it challenging to apply, but it was better.

- Students scoffed at my 5 hour estimate for the final paper, indicating it took them much much longer.

- The skill of “summarize an article” was coming up a lot and I should have students practice that specific skill deliberately. It’s a building block for both the reading reflections and the final paper (and any paper, really).

- Lesson 6 (end of Week 3) plan was too much. We were all overwhelmed by then.

- Cut reading reflections to best 4 of 5 rather than requiring all 5.

- A second marker (TA) was essential for actually being able to give timely feedback throughout the course, and reliably grade papers on time by the deadline. (Special thanks to Carolyn Baer!)

Notably, none of these notes were on the tech. Maybe those notes are embedded in my weekly lesson plan notes. I recall getting the hang of annotations at some point during that term. But I can’t help but think about how tech ended up fading into the background in PSYC 217 and PSYC 218 evaluations too. I’m curious to know what students in PSYC 417 put in their comments…

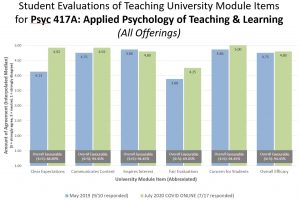

Quantitative Data Summary. The aggregate quantitative data from both offerings appears below. Please click on the graph to enlarge it. Importantly, the response rate was low. Just 7 out of 16 students responded, which is below the threshold for a class this small. Nonetheless, based on the data I have, the second offering went quite well. The most room to grow is in perceived fairness of assessments. I’m not altogether surprised by this, and I’m glad to see a boost from the previous iteration given the changes to the project. The biggest jump was in Clear Expectations — again not surprising given I’d had a chance to actually clarify my expectations.

Qualitative Data Summary. Two key themes emerged from the comments. First, students felt supported in a well-structured course. The asynchronous/ synchronous balance worked well, as did the Canvas structure, and general openness to flexibility. Second, it was a lot of work. Expectations where high (a couple of folks perceived too high), and there were a lot of deadlines. I suspect that some of this intensity will be mitigated by stretching out over 13 weeks rather than condensing into 6, but I still hear the call to think carefully about whether each and every assignment is essential, and where I can build in further flexibility.

Prospective students might be interested in this one comment in particular: “This course is truly intensive. The estimated amount of hours it takes to do this course is way lower than reality. If you are doing anything other than this course in the summer, I wouldn’t recommend it. You will have to produce work above and beyond other high achievers. If you have other commitment in the summer, and produce an average work quality, expect to see lower grades than your average.” I would invite someone who is spending exorbitant hours on this course to meet with me to see if and where to incorporate efficiencies. Yet the point is a valuable one for some folks: this isn’t an easy A. Contrast with someone else’s perspective: “This course reminded me that grades are by far, not the most important part of learning. Nor are they always able to provide sufficient feedback for students. The comments I received on my work far outweighed the value of the grade.”

Two of my favourite comments:

“Taking PSYC417A with Dr. Rawn has genuinely changed my life. Between the quality and frequency of the feedback I received and the fact that the course format was premised upon Self–Determination Theory, I feel I’ve improved more in this course than any other. I believe I’ve improved as a thinker, writer and learner. The information communicated by Dr. Rawn, together with the course activities, provided a scaffolding for students to gradually become more autonomous in their learning. Her compassion, flexibility, and acumen worked synergistically to construct an environment that felt safe enough for me to push my own limits, and improve in ways I wasn’t aware I could.” — WOW. I am honoured to have had such an impact on this student. Thank you so much, whoever you are, for sharing this feedback.

“Dr. Rawn manages to engage her students in the content, and helps give students the freedom to connect course content to passions outside of the course all while creating an environment that is both accepting, and demands the very best work product. I purposefully look to take courses with her because I am never disappointed. She works so incredibly hard, but makes it look easy.” — Whoever you are, thanks for your ongoing trust in me!

My sincere thanks to everyone who took the time to offer ratings and feedback, and to everyone who journeyed along with me while I learned to teach online from the dining table in my open-concept condo. Although some of the details are a bit blurry by now, I do have a deep sense of how much we all worked to motivate each other and learn together in those unprecedented times. You kept me going.

Follow

Follow