Thank you to each of my students who took the time to complete a student evaluation of teaching this year. I value hearing from each of you, and every year your feedback helps me to become a better teacher. Each year, I write reflections on the qualitative and quantitative feedback I received from each of my courses, and post them here.

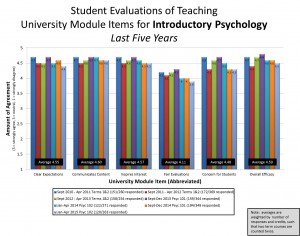

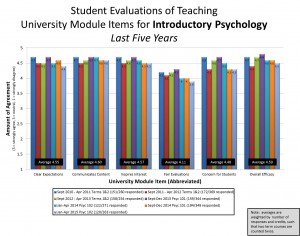

After teaching students intro psych as a 6-credit full-year course for three years, in 2013/2014 I was required to transform it into 101 and 102. Broadly speaking, the Term1/Term2 division from the 6-credit course stays the same, but there are some key changes because students can take these courses in either order from any professor (who uses any textbook). These two courses really still form one unit in my mind so I structure the courses extremely similarly. I have summarized the quantitative student evaluations in tandem. As can be seen in the graph, quantitative ratings of this course haven’t changed too much over the past few years, and students rate my teaching in these courses very similarly. However, I will discuss them separately this year because of some process-based changes I made in 102 relative to 101.

My response to Psyc 101 included a formal coding of comments into various categories. Oh to have the open time of summer! I’m a bit more pressed for time now as I work on my Psyc 102 preparations, so as I was reading the comments I picked out themes a bit less formally. Two major themes emerged (which map on roughly to those identified using more a formal strategy for Psyc 101): class management, and tests. Interestingly, I changed the weighting of the Writing to Learn assignments from Psyc 101 (Term 1 in 2014/15) to Psyc 102 (Term 2 in 2014/15), to avoid relying on peer reviews and just do them for completion points only. The number of comments about that aspect of the course dropped close to zero, despite the actual tasks of the assignment staying the same (see my response to Psyc 101, linked above, for discussion of why I was compelled to make changes in 102 last year).

Again, a major theme in the comments was that tests are challenging. I don’t think they’re any more challenging than in my 101 course, but maybe there’s a perception that they will be easier because the content seems more relatable, and so people are more surprised by the difficulty in 102. Not sure. Just like in my 101, they draw from class content, overlapping content, and some textbook-only content, and they prioritize material that follows from the learning objectives (which I post in advance to help you know what material will be explored in class the next day). MyPsychLab is a source of practice questions, as are your peers and the learning objectives.

In addition to content, time is tight on the tests. Before implementing the Stage 2 group part, my students didn’t have 25 questions in 50 minutes… they had 50 questions in 50 minutes. Now, we have 25 questions in about 28-30 minutes, which is actually more relaxed than before. Although many people report finding value in the group part of the test, it’s not universally loved. A few people mentioned that it’s not worth it because it doesn’t improve grades by very much. My goal here is to promote learning. I’m stuck with the grading requirements: we have to have a class average between 63 and 67%. That’s out of my control. The group tests add an average of about 2% to your test grade, which you may or may not value. But importantly for me, they improve learning (Gilley & Clarkston).

The second most frequent comment topic related to various aspects of classroom dynamics. I thought I’d take this opportunity to elaborate on some choices I make in class.

I do my best to bring high energy to every class. Many people report being fueled by that enthusiasm—that’s been my most frequent comment for many years across many courses. However, a few people don’t love it and feel it’s a bit juvenile or just too much. I bring this up here as a heads up: Although I’d love to have you join us, if you’re not keen on the way I use my voice to help engage people, you might enjoy a different section of 102 better.

In class, occasionally I comment when a student is doing non-course related things on a device, and invite them to join us. A couple of people mentioned this in evaluations from last year. My intention here is to promote learning (i.e., to do my job). Research shows that when people switch among screens on their laptops, they’re not just decreasing their own comprehension, but the comprehension of all the people within view of the screen (Sana, Weston, & Cepeda). I occasionally monitor and comment on this activity (e.g., during films) so that I can create a class climate where anyone who wants to succeed can do so.

Sometimes I wait for the class to settle, and sometimes I start talking to the people in the front (which might be perceived as incomprehensible to the people at the back of the room). I get impatient sometimes too, particularly toward the end of the year (I’m only human after all!). I don’t like to start class until the noise level is settled, out of fairness of people who are sitting at the back but still want to be involved, and, to be honest, talking while others are talking and not listening makes me feel disrespected. One change I made in my 101 class this past term might help us with starting class in 102. I decided to move the announcements from verbal ones at the start of class to a weekly email I send out on Friday afternoons. This change seems to have improved people’s recognition that when I’m ready to start class, we’re starting with content right away, so settling happens more quickly. Hopefully this will help us out in 102.

As always, many thanks for your feedback. It challenges me to think about ways I can improve in my teaching, and to reconsider decisions I have made in the past. Sometimes I make changes, and sometimes I reaffirm the decisions I made before. This space gives me a chance to explain changes or re-articulate why I continue to endorse my past decisions. Student feedback is an essential ingredient to my decision-making process. Thank you!

Follow

Follow