Commentary # 3, Cecilia Tagliapietra

Along this course, we’ve discussed the “creation” or discovery of text and how it has transformed throughout the ages; providing mankind a way of expressing thoughts and feelings. In this third and last commentary, I’d like to discuss how we’ve become literate in different areas and how literacy, as text, has also been transformed to fit new manifestations of text. I’d also like to touch upon the challenges we face as teachers, to assess and impulse the development of these competencies or literacies.

As text has transformed spaces and human consciousness (Ong, 1982, p. 78), we’ve also changed the meaning of the term literacy, integrating not only the focus on text as the main aspect of it, but also the representations, and methods in which text is manifests, as well as the meaning given or understood according to different contexts. The New London Group (1996) has introduced the term “multiliteracies” for the “burgeoning variety of text forms associated with information and multimedia technologies” (p. 60). From this understanding and meaning, we can identify different literacy abilities or competencies. The two most important types of literacies we’ll narrow down to are: digital literacy and information literacy.

Dobson and Willinsky (2009) assertively express that “digital literacy constitutes an entirely new medium for reading and writing, it is but a further extension of what writing first made of language” (referring to the transformation of human consciousness, (Ong, 1982, p. 78)). These authors consider digital literacy an evolution that integrates and expands on previous literacy concepts and processes, as Bolter expresses “Each medium seems to follow this pattern of borrowing and refashioning other media” (Bolter, 2001, pg. 25). With digital literacy, we can clearly identify previous structures and elements shaping into new, globalized and closely related contexts.

Digital technologies have recently forced us to change and expand what we understand as literacy. Being digitally literate is being able to look for, understand, evaluate and create information within the different manifestations of text in non-physical or digital media. Information literacy is also closely linked to the concept of digital literacy. According to the American Association of School Librarians (1998), an information literate, should: access information efficiently and effectively, evaluate information critically and competently, use the information accurately and creatively. We can clearly see an interrelationship between the concepts of these literacies; they both rely on an interpretation of text and an effective use of this interpretation. The development of critical thinking skills is also closely related to these concepts and the ability to use information (and text) creatively and accurately.

The use of these new literacies has also changed (and continues to do so) the way we communicate and learn; we constantly interact with multimedia and rapidly changing information. Even relationships and authority “positions” are restructured, as consumers also become producers of knowledge and text. With the introduction and use of these new literacies, education has somehow been “forced” to integrate these competencies into the curriculum and, most importantly, into the daily teaching and learning phenomena.

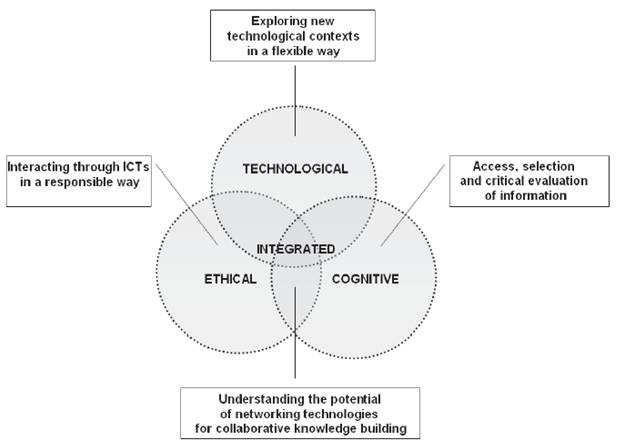

As teachers, we are not only required to facilitate learning in math, science, etc.; we are also required to facilitate and encourage the development of these literacies as well as critical thinking skills. Teaching and assessing these abilities is no easy task, as it’s not always manifested in a concrete product. Calvani and co-authors (Calvani, et.al, 2008), propose an integral assessment for these new competencies, involving the technological, cognitive and ethical aspects of the literacies (See Figure 1). In order to assess, we must initially transform our daily practices to integrate these abilities for our students and for ourselves. Being literate (in the “normal” concept) is not an option anymore. We are bombarded with and have access to massive amounts of information which we need to disseminate, analyze and choose carefully. Digital and information literacies are needed competencies to successfully understand and interpret the globalized context and be able to integrate ourselves into it.

Learning (ourselves) and teaching others to be literate or multi-literate is an important task at hand. Tapscott (1997) has mentioned that the NET generation is multitasker, digitally competent and a creative learner. As educators and learning facilitators, we also need to integrate and develop these competencies within our contexts.

Literacy has transformed and integrated different concepts and competencies, what it will mean or integrate in five years or a decade?

Figure 1: Digital Competence Framework (Calvani, et.al, 2008, pg. 187)

References:

American Association of School Librarians/ Association for Educational Communications and Technology. (1998) Information literacy standards for student learning. Standards and Indicators. Retrieved November 28, 2009 from: http://www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/aasl/guidelinesandstandards/informationpower/InformationLiteracyStandards_final.pdf

Calvani, A. et. al (2008) Models and Instruments for Assessing Digital Competence at School. Journal of e-Learning and Knowledge Society. Vol. 4, n. 3, September 2008 (pp. 183 – 193). Retrieved November 28, 2009 from: http://je-lks.maieutiche.economia.unitn.it/en/08_03/ap_calvani.pdf

Dobson and Willinsky’s (2009) chapter “Digital Literacy.” Submitted draft version of a chapter for The Cambridge Handbook on Literacy.

New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60-92. Retrieved, November 28, 2009, from http://newlearningonline.com/~newlearn/wp-content/uploads/2009/03/multiliteracies_her_vol_66_1996.pdf

Tapscott, Don. Growing Up Digital: The Rise of the Net Generation, Retrieved November 28, 2009 from: http://www.ncsu.edu/meridian/jan98/feat_6/digital.html