Final project, Comment#3

The article “Does the brain like e-books” in our readings is relevant to my educational work since I deal exclusively with adult learners who are not “digital natives” (term after Pranskey, cited in Mabrito & Medley, 2008). A typical student in my online class has grade 12 education, and ages range from 18-65, with many students engaging in online constructivist collaborative learning using modern hypermedia for the first time. The typical student seems to have a period of adaptation which is required for them to become comfortable with the new skills needed for use of computer and Internet, and to develop independent self-learning and critical thinking skills.

The article “Does the brain like e-books” in our readings is relevant to my educational work since I deal exclusively with adult learners who are not “digital natives” (term after Pranskey, cited in Mabrito & Medley, 2008). A typical student in my online class has grade 12 education, and ages range from 18-65, with many students engaging in online constructivist collaborative learning using modern hypermedia for the first time. The typical student seems to have a period of adaptation which is required for them to become comfortable with the new skills needed for use of computer and Internet, and to develop independent self-learning and critical thinking skills.

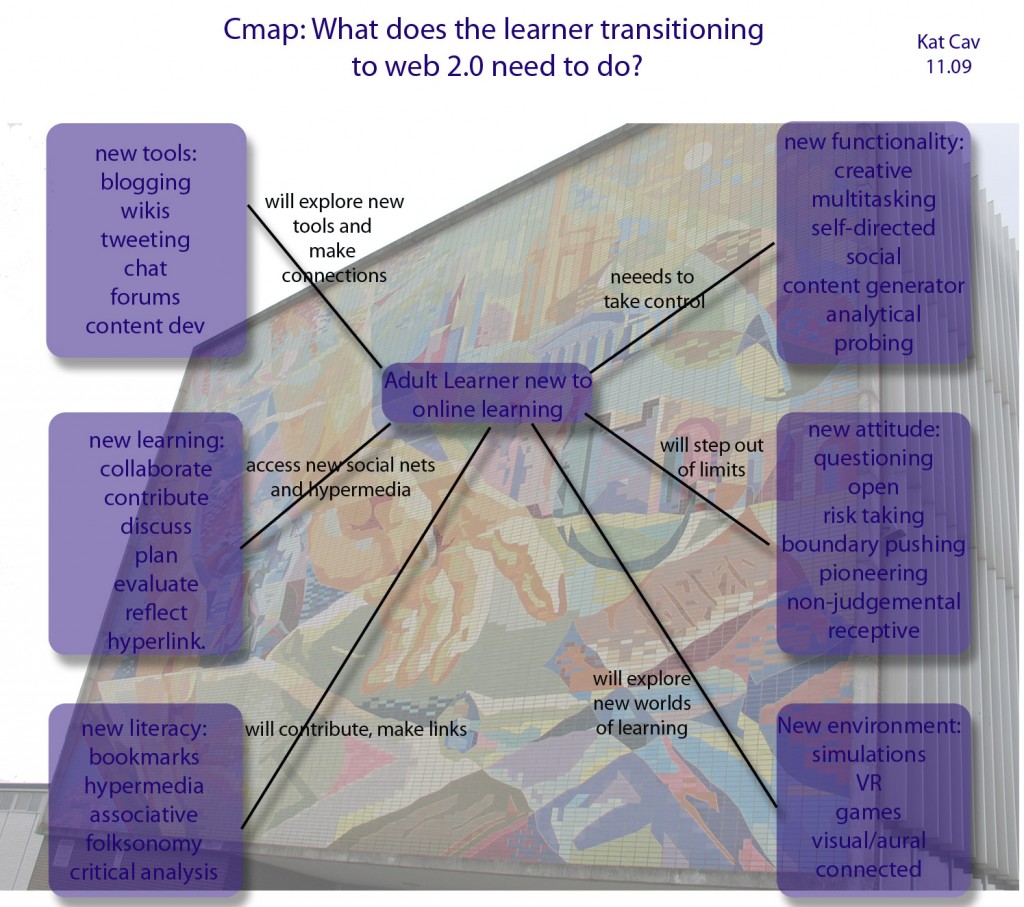

I dealt with the issue of the aspect of independent learning (learning how to learn) “the what” (after the New London Group, 1995, p 24) and its importance for students new to hypermedia in commentary #2. This commentary will focus on the learning of the content itself (the “how”, after the new London Group, 1995, p 24), and the social focus of web 2.0 learning, for students in transition between traditional literacy and learning methods, going into a web 2.0 environment. The research here will help to support or disprove my driving question of whether the transition learning period requires different pedagogy, as my daily observations seem to suggest. This subject is perhaps not as relevant for those in K-12 learning since these students are either digital natives or well versed in multiliteracy (term after the New London Group, 1996), and not faced with many first-time issues. The commentary will close with a reflective summary I developed to help understand integration of teaching initiatives outlined in the New London Group paper.

Other study groups such as Liu’s in California, the ”Transliteracies Project” (October, 2009) are shedding valuable light on this area. Liu reports “Initially, any new information medium seems to degrade reading because it disturbs the balance between focal and peripheral attention”. His observation does seem typical for newly-online learners who do in fact get sidetracked in class. Even for those adult learners with educational backgrounds, some time to adjust is required. In the MET 540 discussion forum Prizeman (2009) observes “The hypertextuality of digital writing spaced at first confused my linear mind, but now that I have spent a great deal of time interacting with them, I feel like “I’ll never go back”!” Her insight certainly reinforces the sense that there is a transitional period.

Liu (October, 2009) also concludes “It takes time and adaptation before a balance can be restored, not just in the “mentality” of the reader…but in the social systems that complete the reading environment.” This makes good sense as all literacy occurs in context, and so the student would be expected to adapt to the new way of learning in a bigger sense. Traditional pedagogy is didactic and students are used to being passive, linear and focused on one package of learning at a time as described in the Mabrito & Medley (2008) article. The Liu group confirms that in early phases of transition to new media “We suffer tunnel vision, as when reading a single page, paragraph, or even “keyword in context” without an organized sense of the whole. Or we suffer marginal distraction, as when feeds or blogrolls in the margin (”sidebar”) of a blog let the whole blogosphere in.”

The multidimensional environment calls on the learner to multitask. The open-ended resources on the Internet can be overwhelming at first as the learner enters this novel research realm. It is not the reading comprehension that suffers, as most students are adept at reading on a screen. In the “Does the Brain like e-Books?” article, Aamodt concludes, “Fifteen or 20 years ago, electronic reading also impaired comprehension compared to paper, but those differences have faded in recent studies.”

Aamodt (October, 2009) also reports that “Distractions abound online — costing time and interfering with the concentration needed to think about what you read. “ The deep concentration which is required to reflect on what is read, heard and seen may be reduced in this type of environment. Learning to focus on the work at hand and dismiss the outliers is a learning strategy that can be coached. Aamondt points out that, “Frequent task switching costs time and interferes with the concentration needed to think deeply about what you read.” Mark (October, 2009) concurs “When online, people switch activities an average of every three minutes (e.g. reading email or IM) and switch projects about every 10 and a half minutes”. That is bound to impact reflective learning. Mark also reports “My own research shows that people are continually distracted when working with digital information” so maintaining focus is confirmed to be a challenge, and her study did not just include learners new to hypermedia. She agrees with Aamondt about depth of engagement, “ It’s just not possible to engage in deep thought about a topic when we’re switching so rapidly.”

Well adapted online learners with established multiliteracy are comfortable with social networking, and multitasking in hypermedia, so more experienced learners will need more flexible environments to correlate with their skill set. Prizeman (2009) in our forums put it very well “The possibilities are endless, and the once hierarchical order that knowledge was presented in print, no longer exists in hypertext–I feel more in control of my learning, and with flexibility and freedom, I am able to search out the information that I need, as well as explore the connections between it and my world.”

The interface with online learning needs to evolve with a new appreciation of interacting with media versus human communication. Ong explores this concept and determines “communication is inter-subjective” (Ong, 2002, p 173). Ong refers to a media model of communication that focuses on informational, performance oriented interpretation, versus true communication which requires one to have advance appreciation for the other person’s inner self. That new setting is important as he points out that getting inside the minds of persons you will never know is not an easy thing to do, “but it is not impossible if you and they are familiar with the literary tradition they work in” (Ong, 2002, p. 174). Learning online does require this re-set of human communication through the window of the computer screen, and learning a new type of literary tradition, which takes time to become internalized.

Guided learning will help to address the distracting environment for transitioning students. Use of learning objectives, goal-oriented learning agreed upon by instructor and student and web or wiki quests help to direct newly-online learners to a subset of what is a large resource pool for relevant information. This limited structure is a guide not a limit. Bolter (2001, p169) points out that “relationship between the author, the text, and the world represented is made more complicated by the addition of the reader as an active participant”. A transitional learner will need to become adapted to the necessity of being more engaged and constructive when interfacing with electronic materials compared with one-way media. Use of RSS feeds can help students find key learning materials that are of high relevance. Another strategy to help a learner in that adaptation phase is to pair them with a mentor who is comfortable in web 2.0, and can be a resource for them. As well, collaborative grouping will allow students to split up a literature search or web search so that each has a self assigned area to focus in. Critical analysis of resources can be integrated with that orientation session. Some of these strategies will only be needed until new-online students’ multiliteracy is established.

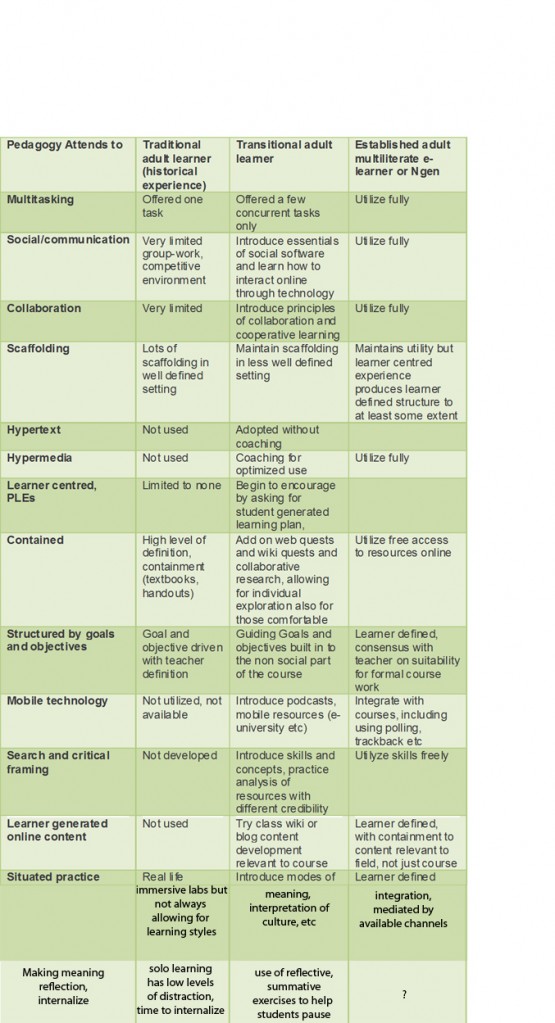

The appendix table below will provide a summary of the critical pedagogy strategies that may be used to cultivate the intellect, and how they can be utilized in courses for learners of varying competence in multiliteracy.

In conclusion, it does appear that the literature supports observations that transitioning learners may need to have some early scaffolding and support and that their learning is constantly evolving through that period. Once transitioned, students can enjoy the full richness of multiliteracy and online networked learning.

A hanging issue is sparked by the observation reported by Mark (October, 2009 in “Does the Brain like e-Books?) “More and more, studies are showing how adept young people are at multitasking. But the extent to which they can deeply engage with the online material is a question for further research” Baxter (2009) mirrors these concerns when she posted “I’m not convinced that getting used to the extra activities does actually enable one to concentrate fully in spite of them. I’m more inclined to think that – along with a lot of other abilities, like amusing themselves during a power outage – the “digital generation” is losing the ability to concentrate fully on something that doesn’t engage them.”

Though these learning strategies summarized below will help us understand the transition to multiliteracy in an online learning environment, that is another realm of future enquiry; addressing the hanging issue of how transitioned students can effectively internalize and reflect on what they have learned which has been left as a question mark in the summary table.

References

Bolter, J.D. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print [2nd ed]. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

[Ed’s] Does the brain like e-books? (October 2009) featuring Liu, A., Aamodt, S, Wolf, M., Mark, G. Accessed online at the New York Times, November 1, 2009 at: from http://roomfordebate.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/10/14/does-the-brain-like-e-books

Ito, M., Horst, H., Bittani, M., Boyd, D., Herr-Stephenson, B., et al. (2008). Living and learning with new media: Summary of findings from the digital youth project. From: macfound.org , University of Southern California and the University of California, Berkeley.

Mabrito, M & Medley, R. (2008). Why Professor Johnny Can’t Read: Understanding the net generation’s texts. Innovate. Vol. 4, No. 6. Retrieved online November 1, 2009 from: http://www.innovateonline.info/index.php?view=article&id=510&action=article Page 1 of 7

New London Group (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, Vol. 66, No. 1, 60-92. Retrieved online from : http://wwwstatic.kern.org/filer/blogWrite44ManilaWebsite/paul/articles/A_Pedagogy_of_Multiliteracies_Designing_Social_Futures.htm

Ong, W. (2002) Orality and Literacy: The technologizing of the word. London: Menthuen.

Prizeman, S. (2009). From Calculator of the humanist-Miller MET ETEC 540 Forum on November 23, 2009 10:34 am.

Baxter, D. (2009). From Origin and nature of hypertext-Miller MET ETEC 540 Forum on November 27, 2009 1:18 pm

November 30, 2009 2 Comments

Rip, Mix, Mashups

HI, for this exercise I elected to do a merger of dada poetry and environmental art by Bansky. As a traditional poet, I am not a particular fan of dada so this is a stretch, but I found an online dada generator and had fun plugging in our readings! If anyone wants it, I can dig it up.

For this exercise I tried slideshare for the first time and did not realize I needed to upload audio files separately. It was pretty easy to use though!

My link is at:

November 29, 2009 1 Comment

Commentary #2 Literacies and Information Architecture

Mandala Making Activity——-

—–As a preface activity to the commentary I would like to invite classmates to review an online example, or generate their own Mandala of Muliliteracy as a way to conceptualize the organization of each individual’s concepts. Feel free to peruse the http://win-dev.communication.utexas.edu/mandala/ communication course website and check out a sampling of other ones on the site.

The Dobson and Willinsky article provides a broad scan of the many meanings of digital literacy, for which they consider technological literacy to be a synonym (p 15, 2009). The paper asks us to focus also on the impact that digital literacy will have socio-culturally. This article served as a springboard to explore the theme here that information architecture skills are integral to successful learning. This would correlate with a structural meaning-making context, after Cope & Kalantzis (p 11, 2009)

The authors make the distinction between traditional literacy and new literacy—they encourage us to view literacy as a social practice, not an individual skill (page 15, 2009). Digital literacy is a presented as a subset of information literacy. The 1989 definition of information literacy (page 18, 2009) cited from the American Library Association is as follows “To be information literate, a person must be able to recognize when information is needed, and have the ability to locate, evaluate, and use effectively the needed information”. Learning to learn is a saying often applied to describe general information literacy.

Matthews-DeNatale (2009) believes “There are at least three pieces to the puzzle. One piece is information technology fluency, one is information literacy, and another piece is media literacy. And they’re all overlapping, like a Venn diagram.” Information management is a part of multiliteracy skills, and will be the focus of this report.

Dobson and WIllinsky also cite earlier work (p 16, 2009) by Dobson (2005) in which he proposes “Digital literacy, therefore, assumes visual literacy and entails both the ability to comprehend what is represented and the ability to comprehend the internal logics and encoding schemes of that representation”. This definition implies that one needs to understand the structure behind the information directly accessed in the media, and so associated with every representation of “data” is metadata.

With projects such as Project Gutenberg, Million Book Project, Google and others the authors refer to (p 17, 2009) today’s student has access to millions of references, and information in multiple media around each subject they may wish to explore.

Dobson and Willinsky propose that accessing multiple nodes between the links in a highly associative environment can be disorienting to a learner (page 7, 2009). This best applies to learners transitioning from traditional learning environments, not to Digital Natives. The authors do clarify that a person with good resident domain knowledge will do better in a high network situation, as they can more easily integrate situational information from this environment with their schemata (page 8, 2009).

Managing information in a digital environment is changing learning both in and out of the classroom. Bookmarking has surfaced as a key way to manage large sets of links on the desktop. Del.icio.us is a perfect example of how an individual can scaffold his or her learning by gradually building up more and deeper resources as understanding of a subject increases. This software allows sharing of bookmarks to further enhance functionality. This sort of tool is good example of the way that digital literacy skills can transform research, which used to be a singular activity, done in libraries’ book stack and index searches, into a highly social activity with potential for many people at great distance and of varying ages and cultural backgrounds to contribute to the process. According to Dede (2008) “RSS feeds, sophisticated search engines, and similar harvesting tools help individuals find the needles they care about in a huge haystack of resources”.

The authors refer to the fact that the unit of importance is now the post, not the page (page 20, 2009). This means that more threads and small packets of information must be managed now that microcontent is king. Behind microcontent is the web of user tags that add another dimension to the material. These linking tags allow pooling of learner knowledge of the data, by the process of cumulative novel associations.

The old way of filing and accessing material was hierarchical and taxonomic. Current information management in multiliterate learners often revolves around folksonomy (Neil, after Vander Wal, 2007). Folskonomy is defined on the EDUCAUSE website as the application of user-defined tags (so-called folk classifications) by an open group of people to categorize units of information ([n.d]). By adding tags to visual or other data in their work, learners can make powerful associative links, and even generate tag clouds, to conceivably make new meaning over and above the data itself. Folksonomy structures such as at Digg, CiteULike and others, provide a new way to manage content. New tools allow one to make a visual representation of the metadata. Generating information architecture over and above the base information is a widespread user-generated experience for the first time in history.

The ability to customize the desktop and files within a personal digital appliance is another way that information literacy skills can enhance learning. Personal Learning Environments (PLEs) provide powerful information structuring, which provides opportunity for deeply customized user-directed learning. PLEs can provide a way for the user to select only those modes of learning and manage information as is best suited to their learning style(s).

Informal learning environments such as games such as SimCity, and social networks (Flickr, Facebook, YouTube) also provide a new way to make meaning by providing situated learning and constructivist experiences. By accessing a path to a level of information which is appropriately in the zone of the student’s development, the comfort of the learner will be enhanced. On YouthVoices for example, young learners share their media together and have online discussions around those materials in a comfortable self-selected sharing environment.

Dobson and Willinsky acknowledge the challenges facing today’s learners when they say “And there are very real issues around too much information, in the form of inundated mailboxes clogged with spam and a World Wide Web that can seem at times overwhelmingly wide, if less than very deep”. (p 22, 2009). If educators are cognizant of the power of information architecture as a component of multiliteracy, then optimizing teaching around this strategy will help the learner focus effectively on both their individual and collaborative learning.

Unorthodox and novel strategies will continue to evolve as software evolves. Google Wave is a high priority research tool for that company because it integrates many multiliteracy tools in one place for streamlined sharing and organizing of information. This is an excellent example of how tools are evolving quickly to come to the aid of web 2.0 users in integration of information architecture. Draude (2009) feels educators should answer the question “Maybe we should look at how to help a student figure out what is the priority information—not what information does the student have to know, but what information can the student go find that will supplement what he or she knows? Dobson and Willinsky (2009) cite a similar theme from a 1989 work by Lemeke regarding students learning independently, using metamedia and information literacy; they quote Lemeke saying”…places the emphasis on “access to information, rather than the imposition of learning”. Draude and Lemeke’s statements certainly represent a new appreciation of just how important information architecture is.

References

Cope, B. & Kalantzis, M. (2009) ‘Multiliteracies’: New literacies, new learning. e-published March 17, 2009; Accessed online November 5, 2009 at: http://newlearningonline.com/~newlearn/wp-content/uploads/2009/03/m-litspaper13apr08.pdf

Dede, C. (2008). A seismic shift in epistemology. EDUCAUSE REVIEW, Vol. 43, No. 3. Pp 80-81. Accesssed online November 15, 2009 at: http://www.educause.edu/EDUCAUSE+Review/EDUCAUSEReviewMagazineVolume43/ASeismicShiftinEpistemology/162892

Dobson, T., Willinsky, J. (2009). Digital literacy. Cambridge Handbook on Literacy. Accessed online at: http://pkp.sfu.ca/files/Digital%20Literacy.pdf

EDUCAUSE. Folksonomies [n.d]. Accessed online November 15th at: http://www.educause.edu/Resources/Browse/Folksonomies/30459

Neal, D. (2007). Folksonomies and Image Tagging: Seeing the Future? ASIS&T Bulletin. Accessed November 15, 2009 online at: www.asis.org/Bulletin/Oct-07/neal.html

Schaeffer, S., Fry, M., Droude, B., Matthews-DeNatale, G. (2009) Information literacy and IT fluency. EDUCAUSE REVIEW Vol. 44, No. 3 pp 8-9. EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative (ELI) Annual Conference podcast at: <http://www.educause.edu/NewTechPodcast>.Under Creative Commons License3.0

Websites Referred to:

Youth Voices http://youthvoices.net/legg/

SimCity http://simcitysocieties.ea.com/index.php

digg http://.digg.com

Flickr http://www.flickr.com

citeulike http://www.CiteULike.org

facebook http://www.facebook.com

Google Wave http://wave.google.com/help/wave/about.html

November 16, 2009 1 Comment

Reflections Modules 1 and 2

I am enjoying the content of the two courses I am taking this semester tremendously, both via readings and sharing by keen and engaged fellow-learners. Unfortunately, I have a sense of missing much since there is such a plethora of material and it rests in many different places, both within course materials/wikis/weblogs/webCT, and via the excellent links to further reading and viewing. As I read through the postings while catching up after the flu, I feel all the salient points have been presented in so many comprehensive ways—what else can I say that is even remotely witty or wise? That adds to the discussion in a meaningful, scholarly way?

In our readings, we have explored the way humans transitioned from primary orality and adapted to new ways of putting pen to “paper”. That process took from 3500 BC to now. Very recently, text is becoming more plastic and functional by integrating hypertext, and news travels very fast by widespread social network collaboration. We are moving away from solo writer, and set in “stone” letters and words, to plastic text—textology is changing fast.

Postman in Technopoly presents a position of concern around new technologies.

In Brands’ Escaping the Digital Dark Age, the loss of digitized data is explored in detail. He admonishes all to sit up and take notice of this hidden risk.

The CBC commentary surrounding the digital universal library concept is a wandering exploration of the issues of copyright, and private corporation involvement. The Kelly article “Scan this Book” explores many similar themes as in the other readings about the universal digital library.

O’Donnell proposed in the Virtual Library piece that the idea is neither new nor golden. He speaks of the historical aspects from The Great Library of Alexandria through the Memex in the ‘40s, and expresses concern that “infochaos” will be the only thing to emerge from the debacle of the dreamed universal digital library of the future.

In the video version of funeral oration of Julius Caesar, and in Phaedrus, we saw classic oratory in the rhetoric form, which was also exemplified in the Plato Iliad excerpt. The irony of the Plato oration is that the written word is the vehicle he uses to expound his theories about the downside of writing, and he proposed that nobody who had serious and important ideas would write them down—how ironic is that! The issue Plato raises of the relationship of memory with written word is revisited in modern times in the Visible Language article, Hypertext and the Art of Memory.

James O’Donnell in “From Papyrus to Cyberspace” explored the flip side of new technologies—the downside, when we do not know fully the effects until after implementation. He believes that unpredictable change and a less intimate community are hallmarks of the modern time. Dr. James Engell feels the state of affairs is that education is already transformed by new technologies, and the generational divide is a big one. He emphasizes instability in business and in information storage as examples of how unclear the future direction is in these frontier times.

Lamb’s article “Wide Open Spaces: Wikis, ready or not” is a good ingress into the next section of the course where we deal with the connections between text and fluidity of the web-based text realm. His thoughts about the use of wikis in academics and otherwise were a refreshing introduction to “wikidom”, the new and evolving kingdom of wikis.

October 11, 2009 No Comments