Commentary 1

Take any classroom in a large urban center in Canada and it is possible to find a first nations learner sitting next to someone from Africa, who is sitting behind someone from India, who is across from someone who is from England. Although this class is rich in cultural diversity, it presents challenges meeting the needs of all the learners. One of the differences that teachers may find in their classes is one of oral-literate cultures. Understanding these differences and knowing how to build on their strengths will help educators to provide relevant and meaningful experiences for their students.

The understanding of the differences between the non-literate and literate cultures has long been of interest to many scholars. In his essay “Biases of the Ear and the Eye” David Chandler (2009) defines the “Great Divide” theories as theories that “tend to suggest radical, deep and basic differences between modes of thinking in non-literate and literate societies.” Read ‘simple versus advanced.’ Chandler goes on to explain that alternatives to the Great Divide theories are the “Continuity” theories. These theories hold that there is not a radical difference in the modes of thinking in non-literate and literate societies, but rather a continuum of thinking. It is recognized that differences in expression and behavior exist, but not to the extremes that great divide theorists would have one believe. Chandler refers to Peter Denny’s comment that “ all human beings are capable of rationality, logic, generalization, abstraction, theorizing, intentionality, causal thinking, classification, explanation and originality.” He goes on to say that we can find greater cultural differences between two literate cultures or two non-literate cultures. He cautions that it is dangerous to presume that non-literate societies are all the same as there can be great variations from society to society or even with-in a single society. One of the books that Chandler recommends reading “which offer(s) excellent correctives to the wild generalizations “ is Literacy and orality, by Ruth Finnegan (1988) who says that it is important to look closely at the uses of orality and literacy, to look for patterns and differences and through this we will avoid making generalizations about poorly understood uses of orality and literacy.

Chandler’s ‘continuum’ of orality and literacy can be found in many of our classrooms today. In order to meet the needs of our different learners we must incorporate cultural sensitivity in the class. Teaching from a culturally sensitive perspective is not just about teaching different cultural holidays, foods and dress. It is about understanding, and honoring the ways of learning and knowing of these different perspectives along the continuum. In his address “How to eradicate illiteracy without eradicating illiterates “to UNESCO, Munir Fasheh tells the story of his illiterate mother who was a seamstress. One day after many years of believing that he should “fix” her, making her literate, he saw her take many pieces of cloth and form it into “ a new and beautiful whole”. It was through the act of creating clothing for her customers that he saw her as a wise and knowing person. He recognized that she knew math, maybe in a different way than he knew math, but she knew it. Fasheh says that we need to “ become aware of the diversity of ways of learning, knowing, living, perceiving, and expressing – and that such ways cannot be compared along linear measures.” (Fasheh, 2002)

Fasheh shares his fear that our world places too much emphasis on reading and writing. This fear is supported by Havelock (1991) who says that our education system places primary importance on quickly learning to read and write. He challenges us to consider our “oral inheritance” as well. Fasheh cautions “ We need to look not only at what literacy adds … but also at what it subtracts or makes invisible.” (Fasheh, 2002)

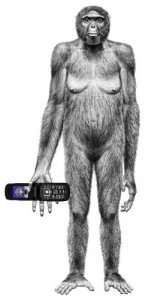

Constructivism is a current and popular learning theory that holds that learners generate knowledge and meaning through their life experiences. This theory recognizes that the cultural background of the learner plays a significant role in the learners understanding of the world. Wertch (1997) tells us that it is crucial that we recognize and honour the learner’s cultural background as this background will help to shape and create the understanding that the learner constructs. If we recognize that some learners come from an oral culture we can use that information and the strengths of learning in an oral culture to provide more appropriate learning opportunities. Croft (2002) in her article Singing under a tree: does oral culture help lower primary teachers be learner-centered? suggests that learner-centered strategies (an important feature of constructivist teaching) that are developed in literate cultures may not be relevant in teaching in an oral based culture. She suggests that the pedagogies used should be developed from the local context. If the learners come from a primarily oral-based culture, use the strengths of that oral culture. Havelock (1991) even suggests that orality is really a part of all of us. “Oral inheritance is as much a part of us as the ability to walk upright.” (p.21) and that all class rooms should encourage singing, dancing and recitations.

Understanding the differences between oral and literate cultures is important, not to compare, but to build on that understanding. Chandler reminds us that that social context with which we use the specific medium is really what is most important, not that one is better than the other. Honoring and celebrating both mediums will make our classrooms places of tolerance where no one is invisible.

References

Chandler, D. (2009). Biases of the Ear and the Eye. Retrieved from http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/litoral/litoral1.html retrieved Oct.4, 2009

Croft, A. (2002). Singing under a tree: does oral culture help lower primary teachers be learner-centred? Internatinal Journal of Educational Development , 22, 321-337.

Fasheh, M. (2002). How to iradicate Illiteracy without iradicating Illiterates. For the UNESCO round table on “Literacy As Freedom.” On the occasion of The International Literacy Day 9-10 September 2002, UNESCO, Paris. Paris.

Havelock, E. (1991). The oral-literature equation : a formula for the modern mind. In D. &. Olson, Literacy and Orality (pp. 11-27). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wertsch, J. (1988). Vygotsky and the Social Formation of Mind. Harvard University Press.

Cultural Relevance