Remediation

“…a newer medium takes place of an older one, borrowing and reorganizing the characteristics of writing in the older medium and reforming its cultural space.” (Bolter, 2001, p. 23)

Bolter’s (2005) definition of remediation struck me a bit like a Eureka! moment as I sat at lunch in the school staffroom, overhearing a rather fervent conversation between a couple of teachers, regarding how computers are destroying our children. They noted how their students cannot form their letters properly, and can barely print, not to mention write in cursive that is somewhat legible. The discussion became increasingly heated as one described how children could not read as well because of the advent of graphic novels, and her colleague gave an anecdote about her students’ lack of ability to edit. When the bell rang to signal the end of lunch, out came the conclusion—students now are less intelligent because they are reading and writing less, and in so doing are communicating less effectively.

In essence, my colleagues were discussing what we are losing in terms of print—forming of letters, handwriting— the physicality of writing. However, I wonder how much of an impact that makes on the world today, and 20 years from now when the aforementioned children become immersed in, and begin to affect society. Judging from the current trend, in 20 years time, it is possible that most people will have access to some sort of keypad that makes the act of holding a pen obsolete. Yes, it is sad, because calligraphy is an art form in itself, yet it strikes me that having these tools allow us the time and brain power to do other things. Take for example graphic novels. While some graphic novels are heavily image-based, there are many that have a more balanced text-image ratio. In reading the latter, students are still reading text, and the images help them understand the story. By making comprehension easier, students have the time and can focus brain processes to create deeper understanding such as making connections with personal experiences, other texts or other forms of multimedia.

As for the communications bit, Web 2.0 is anything but antisocial. Everything from blogs, forums, Twitter, to YouTube all have social aspects to them. People are allowed to rate, tag, bookmark and leave comments. Everything including software, data feeds, music and videos can be remixed or mashed-up with other media. In academia, writing articles was previously a more isolated activity, but with the advent of forums like arxiv.org, scholarly articles could be posted, improved much more efficiently and effectively compared to the formal process that occurs when an article is sent in to a journal. More importantly, scholarly knowledge is disseminated with greater ease and accuracy.

Corporations and educational institutions are beginning to see a large influx of, and reception for Interactive White Boards (IWB). Its large monitor, computer and internet-linked, touch-screen abilities make it the epitome of presentation tools. Content can be presented every which way—written text, word processed text, websites, music, video, all (literally) at the user’s fingertips. The IWB’s capabilities allow for a new form of writing to occur—previously, writing was either with a writing instrument held in one’s hand, or via typing on a keyboard. IWBs afford both processes to occur simultaneously, alternately, and interchangeably. If one so chooses, the individual can type and write at the same time! IWBs are particularly relevant to remediation of education and pedagogy itself, because the tool demands a certain level of engagement and interaction. A lesson on the difference between common and proper nouns that previously involved the teacher reading sentences and writing them on the board, then asking students to identify them—could now potentially involve the students finding a text of interest, having it on the IWB, then students identifying the two types of nouns by directly marking up the text with the pen or highlighter tools.

Effectively, the digital world is remediating our previous notion of text in the sense of books and print. Writing—its organization, format, and role in culture is being completely refashioned.

References

Bolter, J. D. (2001). Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print (2 ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

December 13, 2009 No Comments

Making [Re]Connections

This is one of the last courses I will be taking in the program and as the journey draws to a close, this course has opened up new perspectives on text and technology. Throughout the term, I have been travelling (more than I expected) and as I juggled my courses with the travels, I began to pay more attention to how text is used in different contexts and cultures. Ong, Bolter and the module readings were great for passing time on my plane rides – I learned quite a lot!

I enjoyed working on the research assignment where I was able to explore the movement from icon to symbol. It gave me a more in-depth look at the significance of visual images, which Bolter discusses along with hypertext. Often, I am more used to working with text in a constrained space but after this assignment, I began thinking more about how text and technologies work in wider, more open spaces. By the final project, I found myself exploring a more open space where I could be creative – a place that is familiar to me yet a place that has much exploration left to it – the Internet.

Some of the projects and topics that were particularly related to this new insight include:

E-Type: The Visual Language of Typography

A Case for Teaching Visual Literacy – Bev Knutson-Shaw

Language as Cultural Identity: Russification of the Central Asian Languages – Svetlana Gibson

Public Literacy: Broadsides, Posters and the Lithographic Process – Noah Burdett

The Influence of Television and Radio on Education – David Berljawsky

Remediation of the Chinese Language – Carmen Chan

Braille – Ashley Jones

Despite the challenges of following the week-to-week discussions from Vista to Wiki to Blog and to the web in general, I was on track most of the time. I will admit I got confused a couple of times and I was more of a passive participant than an active one. Nevertheless, the course was interesting and insightful and it was great learning from many of my peers. Thank you everyone.

December 1, 2009 1 Comment

Hypermedia and Cybernetics: A Phenomenological Study

As with all other technologies, hypermedia technologies are inseparable from what is referred to in phenomenology as “lifeworlds”. The concept of a lifeworld is in part a development of an analysis of existence put forth by Martin Heidegger. Heidegger explains that our everyday experience is one in which we are concerned with the future and in which we encounter objects as parts of an interconnected complex of equipment related to our projects (Heidegger, 1962, p. 91-122). As such, we invariably encounter specific technologies only within a complex of equipment. Giving the example of a bridge, Heidegger notes that, “It does not just connect banks that are already there. The banks emerge as banks only as the bridge crosses the stream.” (Heidegger, 1993, p. 354). As a consequence of this connection between technologies and lifeworlds, new technologies bring about ecological changes to the lifeworlds, language, and cultural practices with which they are connected (Postman, 1993, p. 18). Hypermedia technologies are no exception.

To examine the kinds of changes brought about by hypermedia technologies it is important to examine the history not only of those technologies themselves but also of the lifeworlds in which they developed. Such a study will reveal that the development of hypermedia technologies involved an unlikely confluence of two subcultures. One of these subcultures belonged to the United States military-industrial-academic complex during World War II and the Cold War, and the other was part of the American counterculture movement of the 1960s.

Many developments in hypermedia can trace their origins back to the work of Norbert Wiener. During World War II, Wiener conducted research for the US military concerning how to aim anti-aircraft guns. The problem was that modern planes moved so fast that it was necessary for anti-aircraft gunners to aim their guns not at where the plane was when they fired the gun but where it would be some time after they fired. Where they needed to aim depended on the speed and course of the plane. In the course of his research into this problem, Wiener decided to treat the gunners and the gun as a single system. This led to his development of a multidisciplinary approach that he called “cybernetics”, which studied self-regulating systems and used the operations of computers as a model for these systems (Turner, 2006, p. 20-21).

This approach was first applied to the development of hypermedia in an article written by one of Norbert Wiener’s former colleges, Vannevar Bush. Bush had been responsible for instigating and running the National Defence Research Committee (which later became the Office of Scientific Research and Development), an organization responsible for government funding of military research by private contractors. Following his experiences in military research, Bush wrote an article in the Atlantic Monthly addressing the question of how scientists would be able to cope with growing specialization and how they would collate an overwhelming amount of research (Bush, 1945). Bush imagined a device, which he later called the “Memex”, in which information such as books, records, and communications would be stored on microfilm. This information would be capable of being projected on screens, and the person who used the Memex would be able to create a complex system of “trails” connecting different parts of the stored information. By connecting documents into a non-hierarchical system of information, the Memex would to some extent embody the principles of cybernetics first imagined by Wiener.

Inspired by Bush’s idea of the Memex, researcher Douglas Engelbart believed that such a device could be used to augment the use of “symbolic structures” and thereby accurately represent and manipulate “conceptual structures” (Engelbart, 1962).This led him and his team at the Augmentation Research Center (ARC) to develop the “On-line system” (NLS), an ancestor of the personal computer which included a screen, QWERTY keyboard, and a mouse. With this system, users could manipulate text and connect elements of text with hyperlinks. While Engelbart envisioned this system as augmenting the intellect of the individual, he conceived the individual was part of a system, which he referred to as an H-LAM/T system (a trained human with language, artefacts, and methodology) (ibid., p. 11). Drawing upon the ideas of cybernetics, Engelbart saw the NLS itself as a self-regulatory system in which engineers collaborated and, as a consequence, improved the system, a process he called “bootstrapping” (Turner, 2006, p. 108).

The military-industrial-academic complex’s cybernetic research culture also led to the idea of an interconnected network of computers, a move that would be key in the development of the internet and hypermedia. First formulated by J.C.R. Licklider, this idea was later executed by Bob Taylor with the creation of ARPANET (named after the defence department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency). As a extension of systems such as the NLS, such a system was a self-regulating network for collaboration also inspired by the study of cybernetics.

The late 1960s to the early 1980s saw hypermedia’s development transformed from a project within the US military-industrial-academic complex to a vision animating the American counterculture movement. This may seem remarkable for several reasons. Movements related to the budding counterculture in the early 1960s generally adhered to a view that developments in technology, particularly in computer technology, had a dehumanizing effect and threatened the authentic life of the individual. Such movements were also hostile to the US military-industrial-academic complex that had developed computer technologies, generally opposing American foreign policy and especially American military involvement in Vietnam. Computer technologies were seen as part of the power structure of this complex and were again seen as part of an oppressive dehumanizing force (Turner, 2006, p. 28-29).

This negative view of computer technologies more or less continued to hold in the New Left movements largely centred on the East Coast of the United States. However, a contrasting view began to grow in the counterculture movement developing primarily in the West Coast. Unlike the New Left movement, the counterculture became disaffected with traditional methods of social change, such as staging protests and organizing unions. It was thought that these methods still belonged to the traditional systems of power and, if anything, compounded the problems caused by those systems. To effect real change, it was believed, a shift in consciousness was necessary (Turner, 2006, p. 35-36).

Rather than seeing technologies as necessarily dehumanizing, some in the counterculture took the view that technology would be part of the means by which people liberated themselves from stultifying traditions. One major influences on this view was Marshall McLuhan, who argued that electronic media would become an extension of the human nervous system and would result in a new form of tribal social organization that he called the “global village” (McLuhan, 1962). Another influence, perhaps even stronger, was Buckminster Fuller, who took the cybernetic view of the world as an information system and coupled it with the belief that technology could be used by designers to live a life of authentic self-efficiency (Turner, 2006, p. 55-58).

In the late 1960s, many in the counterculture movement sought to effect the change in consciousness and social organization that they wished to see by forming communes (Turner, 2006, p. 32). These communes would embody the view that it was not through political protest but through the expansion of consciousness and the use of technologies (such as Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes) that a true revolution would be brought about. To supply members of these communes and other wayfarers in the counterculture with the tools they needed to make these changes, Stewart Brand developed the Whole Earth Catalogue (WEC). The WEC provided lists of books, mechanical devices, and outdoor gear that were available through mail order for low prices. Subscribers were also encouraged to provide information on other items that would be listed in subsequent editions. The WEC was not a commercial catalogue in that it wasn’t possible to order items from the catalogue itself. It was rather a publication that listed various sources of information and technology from a variety of contributors. As Fred Turner argues (2006, p. 72-73), it was seen as a forum by means of which people from various different communities could collaborate.

Like many others in the counterculture movement, Stewart Brand immersed himself in cybernetics literature. Inspired by the connection he saw between cybernetics and the philosophy of Buckminster Fuller, Brand used the WEC to broker connections between ARC and the then flourishing counterculture (Turner, 2006, p. 109-10). In 1985, Stewart Brand and former commune member Larry Brilliant took the further step of uniting the two cultures and placed the WEC online in one of the first virtual communities, the Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link or “WELL”. The WELL included bulletin board forums, email, and web pages and grew from a source of tools for counterculture communes into a forum for discussion and collaboration of any kind. The design of the WELL was based on communal principles and cybernetic theory. It was intended to be a self-regulating, non-hierarchical system for collaboration. As Turner notes (2005), “Like the Catalog, the WELL became a forum within which geographically dispersed individuals could build a sense of nonhierarchical, collaborative community around their interactions” (p. 491).

This confluence of military-industrial-academic complex technologies and the countercultural communities who put those technologies to use would form the roots of other hypermedia technologies. The ferment of the two cultures in Silicon Valley would result in the further development of the internet—the early dependence on text being supplanted by the use of text, image, and sound, transforming hypertext into full hypermedia. The idea of a self-regulating, non-hierarchical network would moreover result in the creation of the collaborative, social-networking technologies commonly denoted as “Web 2.0”.

This brief survey of the history of hypermedia technologies has shown that the lifeworlds in which these technologies developed was one first imagined in the field of cybernetics. It is a lifeworld characterised by non-hierarchical, self-regulating systems and by the project of collaborating and sharing information. First of all, it is characterized by non-hierarchical organizations of individuals. Even though these technologies first developed in the hierarchical system of the military-industrial-academic complex, it grew within a subculture of collaboration among scientists and engineers (Turner, 2006, p. 18). Rather than being strictly regimented, prominent figures in this subculture – including Wiener, Bush, and Engelbart -voiced concern over the possible authoritarian abuse of these technologies (ibid., p. 23-24).

The lifeworld associated with hypermedia is also characterized by the non-hierarchical dissemination of information. Rather than belonging to traditional institutions consisting of authorities who distribute information to others directly, these technologies involve the spread of information across networks. Such information is modified by individuals within the networks through the use of hyperlinks and collaborative software such as wikis.

The structure of hypermedia itself is also arguably non-hierarchical (Bolter, 2001, p. 27-46). Hypertext, and by extension hypermedia, facilitates an organization of information that admits of many different readings. That is, it is possible for the reader to navigate links and follow what Bush called different “trails” of connected information. Printed text generally restricts reading to one trail or at least very few trails, and lends itself to the organization of information in a hierarchical pattern (volumes divided into books, which are divided into chapters, which are divided into paragraphs, et cetera).

It is clear that the advent of hypermedia has been accompanied by changes in hierarchical organizations in lifeworlds and practices. One obvious example would be the damage that has been sustained by newspapers and the music industry. The phenomenological view of technologies as connected to lifeworlds and practices would provide a more sophisticated view of this change than the technological determinist view that hypermedia itself has brought about changes in society and the instrumentalist view that the technologies are value neutral and that these changes have been brought about by choice alone (Chandler, 2002). It would rather suggest that hypermedia is connected to practices that largely preclude both the hierarchical dissemination of information and the institutions that are involved in such dissemination. As such, they cannot but threaten institutions such as the music industry and newspapers. As Postman (1993) observes, “When an old technology is assaulted by a new one, institutions are threatened” (p. 18).

Critics of hypermedia technologies, such as Andrew Keen (2007), have generally focussed on this threat to institutions, arguing that such a threat undermines traditions of rational inquiry and the production of quality media. To some degree such criticisms are an extension of a traditional critique of modernity made by authors such as Alan Bloom (1987) and Christopher Lasch (1979). This would suggest that such criticisms are rooted in more perennial issues concerning the place of tradition, culture, and authority in society, and is not likely that these issues will subside. However, it is also unlikely that there will be a return to a state of affairs before the inception of hypermedia. Even the most strident critics of “Web 2.0” technologies embrace certain aspects of it.

The lifeworld of hypermedia does not necessarily oppose traditional sources of expertise to the extent that the descendants of the fiercely anti-authoritarian counterculture may suggest, though. Advocates of Web 2.0 technologies often appeal to the “wisdom of crowds”, alluding the work of James Surowiecki (2005). Surowiecki offers the view that, under certain conditions, the aggregation of the choices of independent individuals results in a better decision than one made by a single expert. He is mainly concerned with economic decisions, offering his theory as a defence of free markets. Yet this theory also suggests a general epistemology, one which would contend that the aggregation of the beliefs of many independent individuals will generally be closer to the truth than the view of a single expert. In this sense, it is an epistemology modelled on the cybernetic view of self-regulating systems. If it is correct, knowledge would be the result of a cybernetic network of individuals rather than a hierarchical system in which knowledge is created by experts and filtered down to others.

The main problem with the “wisdom of crowds” epistemology as it stands is that it does not explain the development of knowledge in the sciences and the humanities. Knowledge of this kind doubtless requires collaboration, but in any domain of inquiry this collaboration still requires the individual mastery of methodologies and bodies of knowledge. It is not the result of mere negotiation among people with radically disparate perspectives. These methodologies and bodies of knowledge may change, of course, but a study of the history of sciences and humanities shows that this generally does not occur through the efforts of those who are generally ignorant of those methodologies and bodies of knowledge sharing their opinions and arriving at a consensus.

As a rule, individuals do not take the position of global skeptics, doubting everything that is not self-evident or that does not follow necessarily from what is self-evident. Even if people would like to think that they are skeptics of this sort, to offer reasons for being skeptical about any belief they will need to draw upon a host of other beliefs that they accept as true, and to do so they will tend to rely on sources of information that they consider authoritative (Wittgenstein, 1969). Examples of the “wisdom of crowds” will also be ones in which individuals each draw upon what they consider to be established knowledge, or at least established methods for obtaining knowledge. Consequently, the wisdom of crowds is parasitic upon other forms of wisdom.

Hypermedia technologies and the practices and lifeworld to which they belong do not necessarily commit us to the crude epistemology based on the “wisdom of crowds”. The culture of collaboration among scientists that first characterized the development of these technologies did not preclude the importance of individual expertise. Nor did it oppose all notions of hierarchy. For example, Engelbart (1962) imagined the H-LAM/T system as one in which there are hierarchies of processes, with higher executive processes governing lower ones.

The lifeworlds and practices associated with hypermedia will evidently continue to pose a challenge to traditional sources of knowledge. Educational institutions have remained somewhat unaffected by the hardships faced by the music industry and newspapers due to their connection with other institutions and practices such as accreditation. If this phenomenological study is correct, however, it is difficult to believe that they will remain unaffected as these technologies take deeper roots in our lifeworld and our cultural practices. There will continue to be a need for expertise, though, and the challenge will be to develop methods for recognizing expertise, both in the sense of providing standards for accrediting experts and in the sense of providing remuneration for expertise. As this concerns the structure of lifeworlds and practices themselves, it will require a further examination of those lifeworlds and practises and an investigation of ideas and values surrounding the nature of authority and of expertise.

References

Bloom, A. (1987). The closing of the American mind. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Bolter, J. D. (2001) Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print (2nd ed.). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bush, V. (1945). As we may think. Atlantic Monthly. Retrieved from http://www.theatlantic.com/doc/194507/bush

Chandler, D. (2002). Technological or media determinism. Retrieved from http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/tecdet/tecdet.html

Engelbart, D. (1962) Augmenting human intellect: A conceptual framework. Menlo Park: Stanford Research Institute.

Heidegger, M. (1993). Basic writings. (D.F. Krell, Ed.). San Francisco: Harper Collins.

—–. (1962). Being and time. (J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson, Trans.). San Francisco: Harper Collins.

Keen, A. (2007). The cult of the amateur: How today’s internet is killing our culture. New York: Doubleday.

Lasch, C. (1979). The culture of narcissism: American life in an age of diminishing expectations. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

McLuhan, M. (1962). The Gutenberg galaxy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Postman, N. (1993). Technopoly: The surrender of culture to technology. New York: Vintage.

Surowiecki, J. (2005). The wisdom of crowds. Toronto: Anchor.

Turner, F. (2006). From counterculture to cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the rise of digital utopianism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

—–. (2005). Where the counterculture met the new economy: The WELL and the origins of virtual community. Technology and Culture, 46(3), 485–512.

Wittgenstein, L. (1969). On certainty. New York: Harper.

November 29, 2009 No Comments

The Age of Real-Time

I had the opportunity to go to the Annual Conference on Distance Teaching and Learning in Madison, Wisconsin this past August. The last keynote speaker, Teemu Arina discussed how culture and education are changing with emerging technologies. His presentation illustrated how we are moving from linear and sequential environments to those that are nonlinear and serendipitous. Topics of time, space and social media tie into Teemu’s presentation. The video of the presentation is about 45 minutes long but the themes tie nicely into our course and into many other courses within the MET program.

In the Age of Real-Time: The Complex, Social, and Serendipitous Learning Offered via the Web

November 24, 2009 No Comments

MIT Lab and the “Sixth Sense”

As one of themes of this course relates to technology and information retrieval and storage, I thought I would share this video. The folks at MIT have created a wearable device that enables new interactions between the real world and the world of data. The device, based on personal criteria that you input, allows you to interact with an environment and call up relevant information about it, simply by gesturing (e.g. while shopping a hand gesture will bring up information about a particular product). What is controversial about this device is that it makes it easy to infringe on people’s privacy. Filming and photographing can occur by simply moving one’s hand. Also, think about how annoying it is to listen to a multitude of mobile users chat in public spaces – this device allows a user to project and display information on any surface. Imagine, hundreds of people displaying information all over the place at once!

November 24, 2009 1 Comment

Rip.Mix.Feed Photopeach

Hi everyone,

For my rip.feed.mix assignment, I decided not to re-invent the wheel, but instead to add to an already existing wheel. When I took ETEC565 we were asked to produce a similar project when exploring different web 2.0 tools. We were directed to The Fifty Tools. I used PhotoPeach to create my story. My wife and I moved to Beijing in the fall of 2007 and we’ve been traveling around Asia whenever we get a break from teaching. The story I’ve made is a very brief synopsis of some of our travels thus far. Since the original posting, I have updated the movie with more travels. You can view the story here. If you’re in China, the soundtrack U2 – Where the Streets Have No Name will not play because it is hosted on YouTube.

What I enjoy most about these tools is that they are all available online, all a student needs to create a photo story is a computer with access to the Internet. To make the stories more personal, it would be great if they had access to their own digital pictures. However, if they have no pictures of their own, they can find pictures, through Internet searches that give results from a creative commons license to include in their stories.

Furthermore, as I teach in an international school in which most students speak English as a second, third, or fourth language, and who come from many different countries, Web 2.0 has “lowered barrier to entry may influence a variety of cultural forms with powerful implications for education, from storytelling to classroom teaching to individual learning (Alexander, 2006).” Creating digital stories about their own culture provides a medium through which English language learners acquire foundational literacies while making sense “of their lives as inclusive of intersecting cultural identities and literacies (Skinner & Hagood, p. 29).” With their work organized, students can then present their work to the classmates for discussion and feedback, build a digital library of age/content appropriate material, and share their stories with global communities (Skinner & Hagood).

John

References

Alexander, Bryan. (2006). “Web 2.0: A New Wave of Innovation for Teaching and Learning?” EDUCAUSE Review, 41(2).

Skinner, Emily N. & Hagood, Margaret C. (2008). “Developing Literate Identities With English Language Learners Through Digital Storytelling.” The Reading Matrix, 8(2), 12 – 38.

November 22, 2009 2 Comments

Images Before Computers

“My sense is that this is essentially a visual culture, wired for sound – but one where the linguistic element… is slack and flabby, and not to be made interesting without ingenuity, daring, and keen motivation. (Bolter, p. 47.) Bolter quotes Jameson in The Breakout of the Visual for the purpose of illustrating how “very different theorists agree that our cultural moment – what we are calling the late age of print – is visual rather than linguistic.” (Bolter, p48) One needs only to look around us and see how prevalent images are in our everyday life especially when pertaining to advertising on the outside on billboards, busses and storefronts. The space is limited therefore the images have to be much more compelling without actually using a lot of words.

Both Kress and Bolter assert that the use of image over print is a relatively new phenomenon which has happened as a result of computer use and hypertext. If we look at the history of advertising, we can see that the shift was occurring and becoming culturally entrenched before the wide use of computers. Bolter asserts that “in traditional print technology, images were contained by the verbal text.” (p.48) He is absolutely right when referring to books and magazine articles but when looking at printed ads, we can see that images play a more primal role.

Since we live in a commercially driven capitalist (market) society which is highly dependent on the sale of unnecessary items, much capital and research has gone into how to sell every product imaginable. It may have become a cliché, but only because it is true – sex sells. Here is a very interesting web site that highlights some of the more ludicrous examples. (http://inventorspot.com/articles/ads_prove_sex_sells_5576)

United States and Canada are made up of many people, representing various diverse cultures and languages. Images are pretty much universal although we do have to be careful as some may not be as universal as others. “The main point is that the relationship between word and image is becoming increasingly unstable, and this instability is especially apparent in popular American magazines, newspapers, and various forms of graphic advertising.” (p.49) I would assert that the relationship was already unstable when computers became prevalent. Computers allowed people the forum of discussion and quick access to the images which were previously viewed in isolation. There is no doubt that hypertext allows a further foray into the world of image and freed the image from the binding of the text. Kress points out the obvious and is not always correct. When he states that “[the] chapters are numbered, and the assumption is that there is an apparent building from chapter to chapter: [they] are not to be read out of order. [at] the level of chapters, order is fixed.” (Kress, p.3) It is a mistake to limit our study of the remediation of print by simply looking at text in books. If we expand our focus, as we must to properly discuss the subject, and include magazines and printed ads, evidence clearly points to the fact that the image was becoming more dominant before the prevalent use of computers. Like books, magazines and authors who wrote for them also knew “about [their] audience and … subject matter” (Kress p.3). Unlike books where the order is very rigid, a magazine can be read in any order you like.

Bolter acknowledges the influence of magazines and advertising on remediating text and images by stating that in Life magazine and People magazine “the image dominates the text, because the image is regarded as more immediate, closer to the reality presented.

Bolter’s use of the shaving picture from the USA Today is an excellent example of images becoming central in print. However, I think he is being generous when he states that “designers no longer trusted the arbitrary symbolic structure of the graph to sustain its meaning … .” (Bolter, p.53) I see it more as more pandering to the lowest common denominator. The designers do not trust the public’s ability to read a graph rather than the graph’s ability to “sustain its meaning.” (Bolter, p. 53) It seems that the need to dummy text down is a comment not only on the writer’s faith in the public’s ability to interpret text but also to interpret images. Images are becoming more and more basic and try to appeal to our primal senses and needs – for instance, using sex as a vehicle to increase sales.

The existence of the different entry points speaks of a sense of insecurity about the visitors. This could also be described as a fragmentation of the audience—who are now no longer just readers but visitors, a different action being implied in the change of name, as Kress points out.

Kress succinctly addresses the power of the image in the example of Georgia’s drawing of her family. We can clearly see the differences and interpret them the way the creator of the drawing intended. The placement of the little girl in the drawing tells us about how she views herself in terms of her place in the family. There are no words and none are needed for the image really is worth a thousand words.

Perhaps it is fitting that in this fast paced world we live in, we are moving away from the art of writing, which does take time to both produce and consume to the image which takes time to produce but is designed to be consumed very quickly. However, to tie this change directly to the rise in the use of computers is to blind oneself to the rich legacy of printed images in advertising prior.

Bolter, D. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print [2nd edition]. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Kress, G. (2005). Gains and losses: New forms of texts, knowledge, and learning. Computers and Composition, 22(1), 5-22.

Inventor Spot. (2009). 15 Ads That Prove Sex Sells… Best? Retrieved 12 November, 2009, from http://inventorspot.com/articles/ads_prove_sex_sells_5576

November 15, 2009 1 Comment

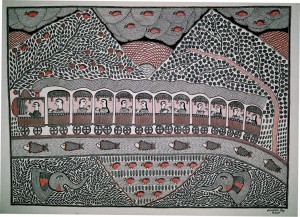

Mithila Art as a Communication Technology

Long before there were computers in most of our homes, there was Mithila Art in homes of what is now India and Nepal. Originally, this folk art form mainly consisted of lively murals painted on the walls of homes in rural villages. But it was much more than simple art for art’s sake. “Mithila painting is part decoration, part social commentary, recording the lives of rural women in a society where reading and writing are reserved for high-caste men” (Arminton, Bindloss & Mayhew, 2006, p. 315). This was art that gave a voice to powerless rural women as a communication technology.

Long before there were computers in most of our homes, there was Mithila Art in homes of what is now India and Nepal. Originally, this folk art form mainly consisted of lively murals painted on the walls of homes in rural villages. But it was much more than simple art for art’s sake. “Mithila painting is part decoration, part social commentary, recording the lives of rural women in a society where reading and writing are reserved for high-caste men” (Arminton, Bindloss & Mayhew, 2006, p. 315). This was art that gave a voice to powerless rural women as a communication technology.

Historical and Cultural Context

This art form acquired its name from the kingdom of Mithila where it originated around the seventh century A.D. At that time, the region was a vast plane located primarily in what is now eastern India as well as in southern Nepal. However, the cultural center and capital of the region was in what is now the city of Janakpur, Nepal only 20 kilometers from the Indian boarder. Janakpur is of course the home of Janakpur painting while the town of Madubandi, India is home of paintings of the same name. Mithila art consists of both kinds of paintings of which Madubandi are more common.

It is said that Mithila art was born when King Janak commissioned artists to create paintings at the time of the marriage of his daughter, Sita, to the god Lord Ram. This might have to do with the fact that most Madubani paintings are created during festivals celebrating marriages and births, religious and social events and ceremonies of the Maithil community. Others say that, “Its original inspiration emerged out of the local women’s craving for religiousness and an intense desire to be one with god” (Janakpur Women’s Development Center, n.d.). However it actually began is not clear, but what it became after being passed down through many generations surly is.

“Mithila is a wonderful land where art and scholarship, laukika and Vedic traditions flourished together in complete harmony between the two” (Mishra, 2009, 4). This harmony was uncommon during this time in many other regions in southern Asia as well as the rest of the world. The general attitude toward artists in this region is one of utmost respect and they were even compared with gods. That could be a major reason why women in ancient Indian society, whom were traditionally regarded as much less significant than men, adopted Mithila art as well as other art forms as not only a communication technology, but as a means for empowerment as well.

“Picture writing is perhaps constructed culturally (even today) as closer to the reader, because it does not depend upon the intermediary of spoken language and seems to reproduce places and events directly” (Bolter, 2001, p. 59). The murals were originally painted during important community events as a kind of subjective snapshot as well as social commentary. This was a positive way for rural women to have a voice and to be heard.

Implications for Literacy and Education

In a communicative context, ‘literacy’ is commonly defined as “the ability to read and write” where to ‘write’ is defined as to “mark (letters, words, or other symbols) on a surface, with a pen, pencil, or similar implement” (Oxford University Press, 2009). So although most Mithila artists were not literate in phonetic writing, they were exceptionally literate in picture writing. As with oral communication, this type of literacy served to bring people together and strengthen their communities. “As we look back through thousands of years of phonetic literacy, the appeal of traditional picture writing is its promise of immediacy. By the standard of phonetic writing, however, picture writing lacks narrative power” (Bolter, 2001, p. 59). The “narrative power” of which Bolter refers to, is the ability of phonetic writing to convey detailed information from a first person perspective. Unfortunately, this ability also has a tendency to actually distance those in communication rather than bring them together as in picture writing.

Bolter goes on to write that, “Sometimes, particularly when the picture text is a narrative, the elements seem to aim for the specificity of language. Sometimes, these same elements move back into a world of pure form and become shapes that we admire for their visual economy” (2001, p. 63). This explains the duality of this art form as both a communication technology and an aesthetic art form. Another perspective of visual communication technologies is that, “Display is, in respect to its prominence and significance and ubiquity, the analogue of narrative” (Kress, 2005, p.14). So while Mithila paintings perhaps lacked the ability to convey a first person narrative, they narrowed the gap between the composer and her audience in a beautiful visual mode of communication.

For the Maithil artists, the ability to express their desires, dreams, expectations, hopes and aspirations to their community in (picture) writing through their painting was most likely much more valuable than communicating detailed information to outsiders by means of phonetic writing. “Unlike words, depictions are full of meaning: they are always specific. So on the one hand there is a finite stock of words—vague, general, nearly empty of meaning; on the other hand there is a n infinitely large potential of depictions—precise, specific, and full of meaning” (Kress, 2005, pgs.15-16). The meaning they conveyed through their art was unmistakable and accessible to all. In this case, picture writing literacy did not lead to phonetic or alphabetic writing literacy. It did, however, require education.

As all writing is communication technology, Mithal art required education to master the particular tools, materials and techniques of this unique style of picture writing. Most of these artists were not formally educated and were illiterate in the ways of phonetic reading and writing. But they did have to learn about the range of natural hues that could be derived from preparations and combinations of clay, bark, flowers and berries as well as how to fashion brushes from bamboo twigs and small pieces of cloth (Mishra, 2009).

Conclusion

Although Mithila art did not directly lead ancient India to a conventional sense of literacy nor to formal education of the masses, it did give a voice to the voiceless. As a communication technology, it provided something for those artists that was and remains a critical element of their society: a heightened consciousness. As Ong writes, “Technologies are not mere exterior aids but also interior transformations of consciousness, and never more than when they affect the word. Such transformations can be uplifting. Writing heightens consciousness” (2002, p. 81).

Mithila art still exists today, but unfortunately has been commercialized with the introduction of tourism. Much of what this art form and communication technology was and did for these people has been lost. Most pieces are painted on paper and many are of scenes made-to-order that have nothing to do with Maithil culture, although selling their artwork has proved an increasing source of income and has in turn improved their quality of live. With the support and guidance development organizations, groups are now promoting the consumption of Vitamin A, voting, safe sex, and saying “no” to drugs to their communities (Janakpur Women’s Development Center, n.d.). So although it has changed considerably over many generations, Mithila art is still a meaningful communication technology.

References

Armington, S., Bindloss, J., & Meyhew, B. (2006). Lonely Planet: Nepal. Oakland, CA: Lonely Planet

Bolter, D. (2001). Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Janakpur Women’s Development Center. (n.d.). Retrieved October 3, 2009, from http://web.mac.com/nadjagrimm/iWeb/JWDC/Welcome.html

Kress, G. (2005). Gains and losses: New forms of text, knowledge, and learning. Computers and Composition, 22, 5-22. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science

Mishra, K. K. (2009). Mithila Paintings: Past, Present and Future. Retrieved October 4, 2009 from Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. Web site: http://ignca.nic.in/

Mithila Art – Madhubani Painting and Beyond. (n.d.). Retrieved October 3, 2009, from http://mithilaart.com/default.aspx

Ong, W. J. (2002). Orality and Literacy. New York: Routledge

Oxford University Press. (2009). Ask Oxford. Retrieved October 10th, 2009 from http://www.askoxford.com/

November 2, 2009 1 Comment

Commentary #2 – Which came first, culture or technology?

“It is not a question of seeing writing as an external technological force that influences or changes cultural practices; instead writing is always a part of culture.… technologies do not determine the course of culture or society, because they are not separate agents that can act on culture from the outside.” (Bolter, p. 19)

To answer this question, we need to begin with a definition of ‘culture’ and ‘technology’ as it relates to knowledge. Culture can be defined as “… the integrated pattern of human knowledge, belief, and behavior that depends upon the capacity for learning and transmitting knowledge to succeeding generations.” (Merriam-Webster) Technology is defined as “…the practical application of knowledge especially in a particular area.” (Merriam-Webster) The distinction between each is clear, as is the connection between the two. Culture is about acquiring knowledge while technology is about applying knowledge. There has been some debate about culture and technology and whether they are inseparable or not. This commentary will take a look at three of these arguments.

In Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print, Bolter was very clear as to what he believed, particularly when it came to writing. “The technical and the cultural dimensions of writing are so intimately related that it is not useful to try to separate them…” (Bolter, p. 19) Bolter went to great lengths to explain the connection between technology and culture; how different technologies of writing involved different materials and that these materials were used in different ways and for different reasons. He used ancient writing as an example. Technologies such as papyrus, ink, and the art of book making may have been common to all cultures but what was different were the writing styles and genders of ancient writing and the social and political practices of ancient rhetoric. He argued that modern printing practices followed a similar pattern as does today’s technologies. Computers, browsers, word processors are our writing technologies but these technologies don’t change cultures per say. If anything, culture has a way of initiating changes in technology.

In his book, Orality and Literacy, Ong argued that the introduction of writing and print literacy’s have fundamentally restructured consciousness and culture. In chapter four of his book, Ong discussed the development of script and how this restructures our consciousness. Ong claimed that “…writing (and especially alphabetic writing) is a technology, calling for the use of tools and other equipment… Technologies are not mere exterior aids but also interior transformations of consciousness and never more than when they affect the word.” (Ong, p. 80 – 81) Ong suggested that humans are naturally tool-employing beings and that these tools create opportunities for new modes of expression that would not otherwise exist. He used the example of the violinist who internalizes the technology (violin) making the tool seemly second nature, or a part of the self. “The use of a technology can enrich the human psyche, enlarge the human spirit, intensifying its interior life.” (Ong, p. 82) In terms of culture and technology, Ong’s technological determinism clearly makes it impossible for him to separate the two.

In Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, Marshall McLuhan argued that technology was nothing more than an extension of man. “The shovel we use for digging holes is a kind of extension of the hands and feet. The spade is similar to the cupped hand, only it is stronger, less likely to break, and capable of removing more dirt per scoop than the hand. A microscope, or telescope is a way of seeing that is an extension of the eye.” (Kappelman) When an individual or society makes use of a technology in such a way that it extends the human body or the human mind, it does so at the expense of some other technology which is then either modified or amputated. “The need to be accurate with the new technology of guns made the continued practice of archery obsolete. The extension of a technology like the automobile “amputates” the need for a highly developed walking culture, which in turn causes cities and countries to develop in different ways. The telephone extends the voice, but also amputates the art of penmanship gained through regular correspondence.” (Kappelman) McLuhan later developed a tetrad to explain his theory. It consisted of four questions or laws; what does the technology extend, what does it make obsolete, what is retrieved and what does the technology reverse into if it is overextended. As was the case with Ong, McLuhan did not make any clear distinction between technology and culture.

Bolter disagrees with the assessment of technological determinists like McLuhan’s “extension of man” claim and Ong’s “restructured consciousness”. He uses cause and effect to prove his point. He points to the early beginnings of the World Wide Web, and how technology (hardware and software) was used to create it. According to Bolter, culture was responsible for changing the Web into “… a carnival of commercial and self-promotional Wes sites…” (Bolter, p. 20) Culture then demanded changes to the hardware and software to allow for such things as censorship. “Wherever we start in such a chain of cause and effect, we can identify an interaction between technical qualities and social constructions – an interaction so intimate that it is hard to see where the technical ends and the social begins.” (Bolter, p. 20) Bolter doesn’t adhere to the ‘doom and gloom’ rhetoric of McLuhan who was “…deeply concerned about man’s willful blindness to the downside of technology.” (Kappelman) and he in mindful of Ong who said “Once the word is technologized, there is no effective way to criticize what technology has done with it…” (Ong, p. 79) Instead, Bolter believed that “… it is possible to understand print technology is an agent of change without insisting that it works in isolation or in opposition to other aspects of culture.” (Bolter, p. 19 – 20)

It seems reasonable to assume that because technology can infringe upon culture and culture can impinge on technology, the two are in a sense inseparable. This may not be a case of one coming before the other as much as both of them coexisting at the same time. Either way, we only need to be cognizant of the fact that both will continue to evolve either as a result of or in spite of the other.

References

Bolter, J.D. (2001). Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

culture. (2009). In Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Retrieved October 31, 2009, from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/culture

Kappelman, Todd (July 2002), Marshall McLuhan:”The Medium is the Message”, Probe Ministries. Retrieved from http://www.leaderu.com/orgs/probe/docs/mcluhan.html#text2

Ong, Walter J. (2002). Orality and Literacy (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

technology. (2009). In Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Retrieved October 31, 2009, from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/technology

Picture retrevied from http://stephilosophy.blogspot.com/

October 31, 2009 1 Comment

From Handwriting to Typing

Please visit this link From Handwriting to Typing to view the research project by Catherine Gagnon and Tracy Gidinski.

October 31, 2009 No Comments

Xanadu and Ted Nelson

I found a great site by Ted Nelson called “Ted Nelson’s Computer Paradigm Expressed as One-Liners”. It examines the cultural ramifications of the web and hypertext with a bit of humour. You can visit it here: http://www.xanadu.com.au/ted/TN/WRITINGS/TCOMPARADIGM/tedCompOneLiners.html

A gem under the section titled Two Cheers for the World Wide Web: “The Web is the minimal concession to hypertext that a sequence-and-hierarchy chauvinist could possibly make” (Nelson, 1999)

Reference

Nelson, T. (1999). Ted Nelson’s computer paradigm expressed as one-liners. Available Online 29, October, 2009, from http://www.xanadu.com.au/ted/TN/WRITINGS/TCOMPARADIGM/tedCompOneLiners.html

October 30, 2009 No Comments

Orality and Mythology

In Orality and Literacy, Walter Ong (2002) drew a distinction between cultures characterized by literacy and cultures characterized by “primary orality”, the latter being comprised of “persons totally unfamiliar with writing” (p. 6). By accepting a form of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, the view that a culture’s language determines the way in which its members experience the world, Ong also considered these two types of culture to be two types of consciousness, or “modes of thought” (Ibid, p. 6). While Ong attempted to address how literate culture developed from “oral cultures”– i.e. cultures characterized by primary orality (Ibid, p. 31) – the sharp distinction he drew between the two respective types of consciousness involved in these types of culture makes the question of how this development would have been possible particularly troublesome (Dobson, Lamb, & Miller, 2009).

Ong evidently recognized that there can be what might be called “transitional forms” between primary orality and literacy. He noted that oral cultures in the strict sense hardly existed anymore (Ong, 2002, p. 11), suggesting that cultures may be oral to a large degree even when they have been somewhat influenced by literate cultures. Furthermore, he granted that literate cultures may still bear some of the characteristics of the oral cultures from which they developed, possessing what he called “oral residue” (Ibid, p. 40-1). However, by characterizing literate and oral modes of thought as he did, it is not clear how it could even be possible for the former to arise out of the latter– although it is clear that they must have done so.

One of the main difficulties lies in Ong’s characterization of oral modes of thought as less “abstract” than literate modes. He asserted that all conceptual thought is abstract to some degree, meaning that concepts are capable of referring to many individual objects but are not themselves individual objects (Ibid, p. 49). According to this view, concepts can be abstract to varying degrees depending on how many individual objects they are capable of referring to. The concept “vegetation” is able to refer to all the objects the concept “tree” can and still more, and thus it is a more abstract concept. The oral mode of thought, Ong asserted, utilizes concepts that are less abstract and this makes it closer to “concrete” individual objects.

This notion of concepts being “abstract” is relatively recent, being developed mainly by the philosopher John Locke (1632-1704). In ancient and mediaeval thought, the distinction between the concept “tree” and this tree or that tree would be described as a distinction between a universal and a particular. Locke’s view that universals are “abstract” ideas was based on the theory that they are formed by the mind’s taking away or “abstracting” that which is common to many particulars (Locke, 1991, p. 147). For example, the concept “red” is formed by noticing many red objects and then “abstracting” the common characteristic of redness from all of the other characteristics the objects possess.

A problem with this theory of abstraction as a general explanation of how concepts are formed was pointed out by Ernst Cassirer (1874-1945). Cassirer noted that the theory first of all claims that it is necessary to possess abstract concepts in order to apprehend the world as consisting of kinds of things, and that without them we would only have what William James – and Ong after him (Ong, 2002, p. 102) – called the “big, blooming, buzzing confusion” of sense perception. The theory also claims that to form an abstract concept in the first place it is necessary to notice a common property shared by a number of particular objects. Yet according to the first claim we couldn’t notice this common property if we didn’t already have an abstract concept. We wouldn’t notice that several objects share the property of redness if we didn’t already have the concept “red” (Cassirer, 1946, p. 24-5).

Cassirer’s criticism of abstraction as a theory of concept formation could serve as a particularly valuable corrective to Ong’s account of the distinction between orality and literacy. Cassirer himself offered a similar account of two modes of thinking which he called “mythological” and “discursive”. The “mythological” mode of thought resembled Ong’s “oral” mode in many ways. Like Ong’s oral mode of thought it was a mode of thought closely linked to the apprehension of objects as they stood in relation to practical activity (Ong, 2002, p. 49; Cassirer, 1946, p. 37-8). Also like the oral mode of thought it was associated with the notion that words held magical power, as opposed to the view of words as mere arbitrary signs (Ong, 2002, p. 32-3; Cassirer, 1946, p. 44-5, 61-2).

If Walter Ong’s account of orality and literacy could be synthesized with Cassirer’s distinction between the mythological and the discursive, it would benefit in that the latter is capable of describing a development from one mode of thought to the other without posing the problematic view that this involves increasing degrees of abstraction. The development of the mythological mode into the discursive mode is not the move away from a concrete world of perception to an abstract world of conception, but the move from the use of one kind of symbolic form to the use of another type. Furthermore, as the mythological mode of thought is already fully symbolic it is possible to study this mode of thought by studying the symbolism used in mythological cultures. While the stages of development from the mythological to the discursive described by Cassirer (e.g. perceiving objects as possessing “mana”, seeing objects as appearances of “momentary gods”, polytheistic forms of thinking, and so on) may not be supported by empirical evidence, the kind of analysis that is offered by his theory of “symbolic forms” makes the type of development in question conceivable and provides us with a program for studying it.

References

Cassirer, E. (1946). Language and Myth. (S.K. Langer, Trans.). New York: Dover. (Original work published 1925).

Dobson, T., Lamb, B., & Miller, J. (2009). Module 2: From Orality to Literacy Critiquing Ong: The Problem with Technological Determinism. Retrieved from https://www.vista.ubc.ca/webct/urw/lc5116011.tp0/cobaltMainFrame.dowebct

Locke, John (1991). An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. In M. Adler (Ed.), Great Books of the Western World (Vol. 33). Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica. (Original work published 1698).

Ong, W. J. (2002). Orality and Literacy. New York: Routledge.

October 4, 2009 2 Comments