Major Project – E-Type: The Visual Language of Typography

Typography shapes language and makes the written word ‘visible’. With this in mind I felt that it was essential to be cognizant about how my major project would be presented in its final format. In support of my research on type in digital spaces, I created an ‘electronic book’ of sorts, using Adobe InDesign CS4 and Adobe Acrobat 9. Essentially I took a traditionally written essay and then modified and designed it to fit a digital space. The end result was supposed to be an interactive .swf file but I ran into too many technical difficulties. So what resulted was an interactive PDF book.

The e-book was designed to have a sequential structure, supported by a table of contents, headings and page numbering – much like that of a traditional printed book. However, the e-book extends beyond the boundaries of the ‘page’ as the user, through hyperlinks, can explore multiple and diverse worlds of information located online. Bolter (2001) uses the term remediation to describe how new technologies refashion the old. Ultimately, this project pays homage to the printed book, but maintains its own unique characteristics specific to the electronic world.

To view the book click on the PDF Book link below. The file should open in a web browser. If by chance, you need Acrobat Reader to view the file and you do not have the latest version you can download it here: http://get.adobe.com/reader/

You can navigate through the document using the arrows in the top navigation bar of the document window. Alternatively you can jump to specific content by using the associated Bookmarks (located in left-hand navigation bar) or by clicking on the chapter links in the Table of Contents. As you navigate through the pages you will be prompted to visit websites as well as complete short activities. An accessible Word version of the essay is also available below.

References

Bolter, J.D. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

To view my project, click on the following links:

November 29, 2009 4 Comments

Comic books and graphic novels: The transformation of reading in the classrooom

Introduction

Ask many librarians or classroom teachers and they will often remark that the comic is a low form of the written word and does not denote “serious” reading on the part of their students. Many will not count reading a comic as part of a home reading program or, at the elementary level, will not allow students to read this type of material during class silent reading periods. Even librarians who willingly add them to their collections often dismiss their importance (Tilley, 2008). In recent years however, the tide seems to be turning in favour of these pulpy little stories. Innovative teachers are beginning to accept the role that comics, and their closely related cousins, the graphic novel, are capable of playing in the education of our children (Viadero, 2009).

Accessibility

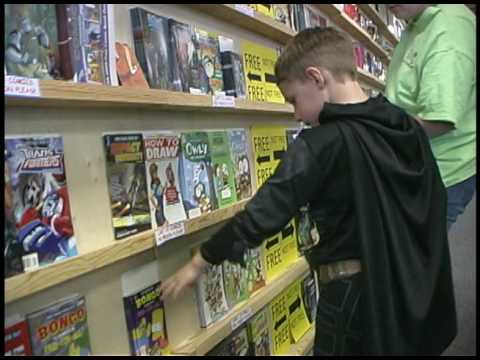

Even though there is evidence of the existence of comics dating back over 150 years they became most readily available during the 1930’s in North American news agents and drugstores (Aleixo & Norris, 2007). This coupled with the low price of the publications made them easily accessible to the public in general and children in particular. In addition there was little competition from other media at that time for, “the time, money, and attention of children” (Jacobs, 2007). Jacobs explains that this ease of availability meant that comics offered a different option for the practice of literacy that was beyond the bounds of a child’s formal education (2007). This increased literacy practice has propelled many children forward as literate members of society and despite the criticisms leveled at the comic world these little books may be better positioned to prepare today’s students for the multiple literacies required in a world where they are constantly inundated by visual images.

Modification and Multimodality

While comics have been much maligned by educators and were even the topic of televised US Senate hearings in 1954 (Kannenburg, 2008), their potential role in literacy education in the classroom is somewhat more positive. It is still rare for teachers to embrace their use in literacy training but it seems that regardless of how scholars define the comic form what seems constant is that in this genre the visual is an important element and, “should not be seen as subservient to the written” (Jacobs, 2007).

It is this combination of text and image that Gunther Kress calls multimodality (Jacobs, 2007). Jacobs maintains that this shift to thinking about comics as multimodal text rather than as a lesser form of writing is significant in the culture of text (2007). It is also significant in terms of understanding the power of comics to teach multiliteracy skills required by today’s students. This valuing of visual literacy has been slow to take hold. Teachers are taught to believe that beginning readers rely on text and that good readers move beyond pictures but the inclusion of comics and graphic novels into the classroom has provided a new generation with an opportunity for layered deconstruction that may help them scrutinize the manner in which interdependent text and imagery creates what has been called, “a strong sequential narrative” (Williams, 2008). This layered deconstruction will involve not only an examination of the text and images but will need to consider the comic author’s use of panels in the creation of the story. These panels guide the reader’s attention and pace the reading in the same way that, “poets use line breaks and punctuation” (Tilley, 2008).

James Bucky Carter (2007) contends that integration of graphic novels into the classrooms of today will transform the study of English. A move away from the notion that literacy is purely text-based will help educators move beyond what he calls, “one size fits all” literacy education (Carter, 2007). This means that the impact of this form of reading may not have had its full impact yet. Its time may still be coming thanks to technological developments that increasingly rely on the user’s ability to process visual images.

Pathways to learning

In many curricular areas the reading of comics affords the educator and the reader a unique opportunity to engage in concepts and ideas that would be, depending on the age of the student, unreachable or difficult in traditional text formats. The inclusion of pictures adds a scaffolding element to learning that can be particularly advantageous in the area of social studies. Williams (2008) argues that, “graphic novels, like a compelling work of art, or a well-crafted piece of writing have the potential to generate a sense of empathy and human connectedness among students”. Visuals combined with text allow comic and graphic artists to ask their readers to consider a different point of view and look at a situation through the eyes of another. In the teaching of social studies this is fundamental to real understanding of both past and current events and represents deep learning on the part of the student.

Conclusion

In these ways, comics and graphic novels will continue to impact and modify our views of text in education. As innovators in the field continue to encourage children to explore this genre the idea that comics are only transitional literature may someday become a thing of the past. Over the past 80 years the progress may have been slow and there have not been any opportunities for comic-like exclamations like “Pow” or “Ka-bam” but new technologies that require a different form of literacy just may be what the comic needs in order to legitimize itself in education.

Resources:

Aleixo, P., & Norris, C. (2007). Comics, Reading and Primary Aged Children. Education & Health, 25(4), 70-73. http://search.ebscohost.com

Burton, D. (1955). COMIC BOOKS: A TEACHER’S ANALYSIS. Elementary School Journal, 56(2), 73-75. http://search.ebscohost.com

Carter, J. (2007). Transforming English with Graphic Novels: Moving toward Our “Optimus Prime.”. English Journal, 97(2), 49-53. http://www.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/Journals/EJ/0972-nov07/EJ0972Transforming.pdf

Jacobs, D. (2007). Marveling at The Man Called Nova: Comics as Sponsors of Multimodal Literacy. (pp. 180-205). http://www.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/Journals/CCC/0592-dec07/CO0592Marveling.pdf

Kannenberg Jr., G. (2008). The Not-So-Untold Story of the Great Comic-Book Scare. Chronicle of Higher Education, 54(37), B19-B20. http://search.ebscohost.com

Tilley, C. (2008). Reading Comics. School Library Media Activities Monthly, 24(9), 23-26. http://search.ebscohost.com

Viadero, D. (2009). Scholars See Comics as No Laughing Matter. Education Week, 28(21), 1-11. http://search.ebscohost.com

Williams, R. (2008). Image, Text, and Story: Comics and Graphic Novels in the Classroom. Art Education, 61(6), 13-19. http://search.ebscohost.com

Williams, V., & Peterson, D. (2009). Graphic Novels in Libraries Supporting Teacher Education and Librarianship Programs. Library Resources & Technical Services, 53(3), 166-173. http://search.ebscohost.com

October 31, 2009 No Comments

First Commentary: Orality and Literacy in Teaching

Ong provides us with some very convincing arguments that there is a marked difference between the thought processes of a purely oral society compared to a literate society. One cannot deny that his examples of the work A. R. Luria appear to show very conclusively that the oral speaker thinks in more lifeworld terms, meanwhile the literate or even semi-literate man is capable of more abstract thinking processes. Ong clearly states that “Literate users of a grapholect such as standard English have access to vocabularies hundreds of times larger than any oral language can manage” (p. 14).On the whole I find myself in agreement with him. However, I have several in laws who are illiterate and when we have problems it is often due to misunderstandings because I have used language in a different way than they do.

Therefore, I find myself left with doubts about the validity of some of his arguments. I wonder if it is really possible for a literate person to know what questions to ask an illiterate person in order to determine their thought processes. I can empathize if I have this skill, but I have been literate all my life. I have had access as Ong quotes Finnegan as saying to “The new way to store knowledge … in the written text. This freed the mind for more original, more abstract thought” (Ong, p. 24).Is it possible to be objective if I have so much more language to command? I believe that as teachers we need to look at orality and literacy at all levels of education. I train teachers from kinder to high school. It is important for kinder teachers to realise how important their use of language is. Children entering kinder garden are being exposed, often for the first time, to new language and new voices. Ong (p.71) explains how one can become immersed in sound. Children love repeated sounds and the use of onomatopoeia and alliteration is crucial for keeping their attention. Small children develop language skills when language is introduced in an additive and aggregative way.

I think almost all teachers would agree that storytelling and giving new information using story telling techniques is a standard practice. However, when we come to older children the reverse is true. Mexico, in particular, is a very sociable and oral culture. However, in the secondary and high school, children until recently, were expected to increase their knowledge by almost exclusively literate means. Whereas, in primary school they were encouraged to vocalise their thoughts, now they are expected to listen to the teacher, read their textbook or investigate on their computers and finally to produce a written document or answer a written exam. Oral skills are not encouraged and children are told to not waste their time talking. It would appear that these teachers believe that “Writing heightens consciousness. Alienation from a natural milieu can be good for us and indeed is in many ways essential for full human life” (Ong, p. 81). Some teachers have tried to change the heavily weighted literary elements of their teaching method by getting their students to present their investigation to the group. Unfortunately, in my opinion, this has not been very successful; as most students read their presentation and some adolescents find it a traumatising experience to be singled out to speak in front of the group.

I became aware of these drawbacks about a few years ago and I have tried to adapt my curriculum accordingly. I see no reason why students have to read alone or in silence. I encourage my students to read aloud in groups and to each other. I find this allows them to stop and discuss relevant points, take notes (written or pictorial) or ask for help if a concept is not clear. I give them options on how to present their knowledge, either, mental or conceptual maps, written summaries, pictorial representations or in oral form. Most of my students come from families were reading is not a common pastime and very few of them read for pleasure. Ong states that “High literacy fosters truly written composition” (p. 94) and I find myself in agreement to some extent. Nevertheless, if a culture does not have very developed literary skills, I believe that it is necessary to find some intermediate path between orality and literacy and from the results I have encountered in my classroom I think that combining orality and literacy is one method that is effective.

Ong, W. (2002). Orality and Literacy. New York: Routledge.

September 29, 2009 2 Comments

Twilight of the Books…is the end near?

I read an interesting article in the New Yorker concerning the history and future of reading for pleasure. Ong and his theory of secondary orality are discussed in the article, but the work of Maryanne Wolf caught my eye (or my mind?). Here is an excerpt of a section which made me think of this week’s readings and Ong’s theory that literate minds would not think as they do were it not for the technology of writing:

“The act of reading is not natural,” Maryanne Wolf writes in “Proust and the Squid” (Harper; $25.95), an account of the history and biology of reading. Humans started reading far too recently for any of our genes to code for it specifically. We can do it only because the brain’s plasticity enables the repurposing of circuitry that originally evolved for other tasks—distinguishing at a glance a garter snake from a haricot vert, say.” (Crain, 2007,¶8)

If this is true, what are the long-term effects of such repurposing? Will we lose the ability to recognize garter snakes? 😉

I am of the opinion that the brain did not “rewire” to adapt to reading, but instead grew (created new connections, new synapses) from literacy. I suppose this could be what Wolf considers “repurposing”, and I admit I have not read her book. However, I don’t think our brain is rerouted resources from one area to another. I think our brains slowly formed new and effective pathways of thought. What do you think?

(There is a nice discussion citing Ong and secondary orality in the article too!) Erin

Crain, C. (2007). Twilight of the books. The New Yorker. Available online 29, September, 2009, from http://www.newyorker.com/arts/critics/atlarge/2007/12/24/071224crat_atlarge_crain?printable=true

September 29, 2009 1 Comment