Category — Commentary 3

Multimodalities and Differentiated Learning

“A picture is worth a thousand words.”

While there are many theories out there on how to meet the needs of diverse learners, there is one common theme—to teach using multimodalities. The strong focus on text in education has made school difficult to a portion of students, students whose strengths and talents lie outside of the verbal-linguistic and visual-spatial-type abilities. Thus the decreasing reliance on text, the incorporation of visuals and other multimedia, and the social affordances of the internet facilitate student learning.

Maryanne Wolf (2008) purports that the human brain was not built for reading text. While the brain has been able to utilize its pre-existing capabilities to adapt, lending us the ability to read, the fact that reading is not an innate ability opens us to problems such as dyslexia. However, images and even aural media (such as audiobooks) take away this disadvantage. Students who find reading difficult can find extra support in listening to taped versions of class novels or other reading material. Also, students with writing output difficulties can now write with greater ease with computers or other aids such as AlphaSmart keyboards.

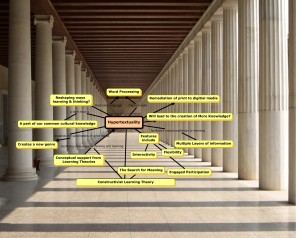

Kress’ (2005) article highlights the difference between the traditional text and multimedia text that we often find on web pages today. While the predecessor used to be in a given order and that order was denoted by the author, Kress notes that the latter’s order is more open, and could be determined by the reader. One could argue that readers could still determine order with the traditional text by skipping chapters. However, chapters often flow into each other, whereas web pages are usually designed as more independent units.

In addition, Kress (2005) notes that texts have only a single entry point (beginning of the text) and a single point of departure (end of the text). On the other hand, websites are not necessarily entered through their main (home-) pages, readers often find themselves at a completely different website immediately after clicking on a link that looks interesting. The fact that there are multiple entry points (Kress) is absolutely critical. A fellow teacher argued that this creates problems because there is no structure to follow. With text, the author’s message is linear and thus has inherent structure and logic, whereas multiple points of entry lends to divergence and learning that is less organized. Thus it is better to retain text and less of the multimedia approach such that this type of structure and logic is not lost. The only problem is that it still only makes sense to a portion of the population. I never realized until I began teaching, exactly how much my left-handedness affected my ability to explain things to others. Upon making informal observations, it was evident that it is much easier for certain people to understand me—lefties.

Kress’ (2005) article discusses a third difference—presentation of material. Writing has a monopoly over the page and how the content is presented in traditional texts, while web pages are often have a mix of images, text and other multimedia.

It is ironic to note that text offers differentiation too. While the words describe and denote events and characters and events—none of these are ‘in your face’—the images are not served to you, instead you come up with the images. I prefer reading because I can imagine it as it suits me. In this sense, text provides the leeway that images do not.

Multimodalities extend into other literacies as well. Take for example mapping. Like words and alphabets, maps are symbolic representations of information, written down and drawn to facilitate memory and sharing of this information. Map reading is an important skill to learn, particularly in order to help us navigate through unfamiliar cities and roadways. However, the advent of GPS technology and Google Streetview presents a change—there is a decreasing need to be able to read a map now, especially when Google Streetview gives an exact 360º visual representation of the street and turn-by-turn guidance.

Yet we must be cautious in our use of multimodal tools; while multimodal learning is helpful as a way to meet the needs of different learners, too much could be distracting and thus be detrimental to learning.

References

Kress, G. (2005). Gains and Losses: New forms of texts, knowledge, and learning. Computers and Composition, 5-22.

Wolf, M. (2008). Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain. New York: Harper Perennial.

December 13, 2009 No Comments

Storage and Performance

I attempted to work through how technologies’ characteristics of storage and performance affect fluency. It represents a start. Please follow this link to see my attempt.

December 6, 2009 No Comments

U-Learning

U-learning seems to be another interesting terminology in the field of education. I saw it first time when I was reading “The World Is Open” book. In that book, Bonk (2009) states that U-learning takes advantage of the capabilities of mobile and wireless technologies to support a seamless and pervasive connection to learning without explicit awareness of the technologies being relied upon. In fact, if you are using technology to learn without reflecting on it, you are likely experiencing u-learning. With the increasing mobility, connectivity, and versatility of educational technologies, there is the potential to devise environments where learning is taking place all the time and for anybody seeking it. And when options for learner participation (not just learning consumption) are added in, learning becomes a more personalized and customized 24/7 experience.

By considering that similar definitions can also be found in other on-line learning fields, in fact, is U-Learning another charming terminology for online education to beat the classroom? Or is it a really new terminology that we need? When I was thinking about these questions I just remembered Bolter saying “hypertextual writing can go further, because it can change for each reader and with each reading”. He also mentioned that technology transforms our social and cultural attitudes toward uses of technology. I think Bolter had predicted today’s learning technologies in 1991, at least in principles.

On the other hand Bolter emphasized that “in the late age of print, however, we are concerned not that there is too much in our minds to get down on paper, but rather that there is too much information held in electronic media for our minds to assimilate”.

Have internet and online technologies, with too much information, changed our minds to assimilate? I also feel that the massive amount of information available to us, from time to time, doesn’t permit us to even think critically to select or make a decision correctly. Maybe, due to lack of time and daily increase in information we have to trust to limited sources or as Bolter said, assimilate our minds. My search in this topic led me to one of the most interesting articles in this area by Salomon and Almog (1998). They started a discussion about “Butterfly” defect.

Salomon and Almog believed that not all of the potential effects with and of learning by means of multimedia and hypermedia are likely to be positive. One of the outstanding attributes of typical hypermedia programs, as well, as the internet, is their nonlinear, association-based structure. One item just leads to another, and one is invited to wander from one item to another, lured by the visual appeal of the presentation. In fact, surfing the internet or hypermedia programs is a good example of a shallow exploratory behaviour, as distinguished from deeper search, a “butterfly-like” hovering from item to item without really touching.

11 years later, in “Lost in Cyburbia”, Harkin (2009) also notes that a problem in the online world is the quick nature of messaging and feedback on Web 2.0 sites. According to him the problem is that people pass on and respond quickly, often giving little time or attention to reflect on the information at hand. He furthers by commenting that users are often in a state of continuous partial attention.

Similar ideas considering a generation of multi taskers who lack focus, can be found in different literature. Bolter, in someway or other, responds to these types of questions by saying “the supporters of hypertext may even argue that hypertext reflects the nature of the human mind itself-that because we think associatively, not linearly, hypertext allows us to write as we think”. He added that “Writing technologies are never external agents that invade and occupy the minds of their users”. New studies by Jones and Khan (2010) supports Bolter that web-based technologies facilitate collaborative knowledge building, development of new ideas and constructs by bringing people with divergent views together.

It seems that learners, and especially young people, should be exposed to all the options they have, learn a bit about each one and from each other and then choose the fields they would like to spend more time perusing in depth studies of. In addition to being pretty democratic, this will also increase their perceptions of learning and motivation to learn. Perhaps, sometimes instead of classic learning theories, a fun theory ! is more appropriate to follow by young generation.

References

Bolter, J.D. (2001). Writing Space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Harkin, J. (2009). Lost in Cyburbia. Toronto: Alfred A. Knopf.

Jones, N., Khan, O. (2010). “Using Web-Based Technologies and Communities of Practice for Transformative Hybrid and Distance Education” in Web-Based Learning Solutions for Communities of Practice: Developing Virtual Environments for Social and Pedagogical Advancement. Information Science Reference. USA.

Salomon, J., Almog, T. (1998). Educational Psychology and Technology: A Matter of Reciprocal Relations, Teachers College Record, no.2, 222-41, Wint ’98.

December 3, 2009 No Comments

Social Media: Changing Perceptions of Authorship, Writing and Publishing

With the advent of social media tools, such as webblogging, social bookmaking, social writing platforms and RSS search engines, our perceptions of writing, publishing and authorship are experiencing dramatic change. How will these changes affect values placed on quantity verses quality, public verses private works, ownership and the ability to create static self contained works? We are in the midst of a transformation which will have significant effects on how we view writing and authorship. In her book, Conversation and Community: The Social Web for Documentation,” Anne Gentle states that through participation in social media “where you can either contribute or motivate others to contribute, you are empowering collaborative efforts unlike any seen in the past.” (2009, 105) In a world of the Internet where anyone can publish and gatekeepers are few and far between, how will the effects of this transition be felt?

Social writing platforms such as Wikis and multi-authored bookmark pages have moved value from individual work to group collaborative wisdom. In these new forms of knowledge output, how will we see authorship and value expertise? Wikipedia offers a collaborative outlet to knowledge demonstration and collection, but without specific gatekeepers regulating content in which “the writer can be the ‘content curator,’ someone who assembles collections based on themes.” (Gentle, 106)

Widely viewed and accessible, Wikis offer both closed and open formats, providing choices for creators in terms of degree of acceptable alteration. (Gentle, 2009) Collaborative knowledge building is becoming increasingly valued as users are “drawing on the wisdom of crowds, [whereby] users contribute content to the work of others, leading to multiple-authored works whose authorship grows over time.” (Alexander, 2009, 153) The result of this co-authored collaborative writing is an experience not bound by physical or temporal limitations. Anyone with basic technological know-how can create a Wiki page and author his work, as “starting a wiki-level entry is far easier than beginning an article or book.” (Alexander, 2009), and anyone with a basic technological know-how can infiltrate and alter content. Modern social technologies may invite alterations and commentaries because the “bar to entry is lower for the average user. A user doesn’t have to author an entire site-just proffer a chunk of content.” (Alexander, 2009, 40)

Shared knowledge online, open to micro-commentary or complete overhaul by fellow Web users, is becoming the norm. Alexander argues that it is “probably inevitable that intellectual property holders will initiate lawsuits investigating perceived misappropriations.” (Alexander, 42) The concept of author control is altered as self-publishers relinquish a large degree of control over their work to others who may be more or less knowledgeable on a subject and carry a varying view point on the subject matter. Contributors in social media spaces need to be willing to restrain from complete domination and control over their writing. (Gentle, 2009) The UBC Wiki site warns users to “note that all contributions to UBC Wiki may be edited, altered, or removed by other contributors. If you do not want your writing to be edited mercilessly, then do not submit it here.” If users do not wish to have the content open to scrutiny and alterations, the UBC Wiki is not the place to post work.

Web 2.0 (also referred to as social media and widget) technologies offer choices between programs best suited for individual user needs depending on the level of openness intrinsic to the technology. Blogging technologies can offer completely open platforms for micro-responses, Google Docs require user invitation to join in the collaborative efforts, and while “a number of wiki platforms permit users to lock down pages from the editing of others” (Alexander, 2009), most Wikis offer open editing possibilities. Creators can decide whether or not to create an online community, a discussion group, or a folksonomy of tagging. (Alexander, 2009) While not all Web 2.0 technologies can be considered online communities, defined by Gentle as “a group of people with similar goals and interests connect and share information using web tools” (103), Alexander (2006) argues that “openness and micro-content combine in a larger conceptual strand…that sees users as playing more of a foundational role in information architecture” in which participants benefit from the collaboration and sharing of information. (Gentle) Levels of openness can affect both process and product by establishing credited contributors or allowing ‘free’ contribution, where “’free’ can mean freedom rather than no cost.” (Gentle) Despite ‘free’ access intrinsic to many social media platforms, “particular types of users are more likely to seek out online communities for information-competent, proficient performers, and expert performers… [over] novices and advanced beginners.” (Gentle, 106)

In terms of asynchronous collaborative writing, the development time line may be short or long, with time spans ranging from days to years, or without a definitive end date. Wikis and other open-knowledge forums have a long end date that makes monitoring more difficult. A Wiki created one year may not be altered until the next, making up-to-date monitoring a challenge. This issue of long verses short term asynchronous communication allows technologies such as Wikis which can be altered indefinitely, very different qualitatively from asynchronous working documents such as Google docs. Programs such as Google Docs allow for continuous asynchronous involvement but generally are developed with an end goal in mind and abandoned as goals are completed. Does this alter the value placed on authorship between short and longer term collaborative writing forums? I would argue the difference is felt in the degree of control the writers can feel in their writing and production.

Online writing has also created a new forum for publishing both in terms of quality and quantity. Writers used to have the option of sharing, but not necessarily publishing and reaching audiences was difficult without publication capabilities. Online writing, in the form of blogging, novels, poetry sites, and article submission has opened the doors for writers in terms of quantity. Alexander states that “[m]any posters to social networking sites publish content for the world to see and use. The blogosphere is a platform for millions of people to write to a global audience.” (Alexander, 2008, 153) Technological know-how can now allow for publication beyond the relatively closed circles of the past. Authorship venues where writers can “voice an opinion, give an honest review, and build an article or diagram or a picture or a video, perhaps by taking on a writing role [allows writers to] feel autonomous and happiness follows.” (Gentle, 110)

Online writing allows for self publishing which ignores the gatekeeper role of publishing houses. What will the implications be for writers who want to pursue formal publishing methods? Formerly, in order to have your work read by a large audience, publishing, whether self of external, was the only means to mass distribution of materials. Web publishing now allows for mass distribution without the quality control of publishing houses but will this make formal publishing increasingly difficult and selective as the quantity of formal publishing houses diminishes and publishing standards alter?

As auto-publishing explodes on the Internet, users are finding novel ways to personalize the Web, effectively ‘writing’ themselves into the World Wide Web. Since the onset of the Internet, search engines have moved from an emphasis on macro searching to both macro and micro searching. Searching on the internet is becoming more personal and independent as users utilise micro search engines such as Blogpulse, Feedster, and Daypop (Alexander) which search based on users’ interests. As search engines move from massive searches, which result in millions of hits, to micro searches, resulting in hits limited to parametres set by the user, the Internet becomes more approachable. (Golder and Huberman) In a sense we are raising the bar of effective levels of navigational abilities where users need to have a purpose in their Web navigation. Programs that are limited to searching blogs, or are program specific such as the soon to be released Google micro-blogging search engine, allow for more user control, directed searching, and stream-lined responses.

To make this point clearer I will use a bookstore analogy. In approaching a bookstore and attempting to navigate within it, a visitor is aware of categories, subcategories and alphabetization. These systems of organization also allow for micro searching based on subject and interest within the physical structure of a bookstore. Micro search engines allow for a similar type of searching of materials. Users can opt to search a certain category as well as response type. Bookstores can also differ from one another qualitatively in terms of audience, geared towards a specific audience such as children, young adults, cooks, teachers, trades people, academics, sports fans, and fantasy enthusiasts. A fantasy enthusiast is not going to look for fantasy material within a book store based on cooking. Micro search engines allow for a similarly controlled searches. Book enthusiasts may enter a mega bookstore which carries a wide variety of books from nearly every genre. Once a specific interest is established, however, the book enthusiast may choose to frequent a more specialized venue, much the same as a micro search engine user may choose to search in a very specific manner over mass broad searches offered through such search engines as Google or Yahoo. (Golder and Huberman)

With small scale search possibilities come other forms of individualized web applications such as social bookmarking and tagging. Where “traditionally…categorizing or indexing is either performed by an authority, such as a librarian, or else derived from the material provided by the authors of the documents…collaborative tagging is the practice of allowing anyone…to freely attach keywords or tags to content.” (Golder and Huberman, 1) Users are able to tag sites that are of interest, creating personalized collections through such applications as del.ici.ous, and allowing users to browse information that has been categorized by others. (Golder and Huberman, 1) Web activity becomes more focused as these programs allow users to streamline their activities through sites of interests and applicability to personal interests. (Golder and Huberman) Social media applications such as Tweetups, are effective in “enabling people to feel related to one another.” (Gentle, 110) Social tagging draws upon collaborative authorship as users work together to tag images, sites, blogs, and ideas in terms of applicability, personal experience and developed networks. (Golder and Huberman)

The formerly impersonal World Wide Web is becoming more personalized, creating ownership amongst users in a way that impersonal surfing could not allow. Micro blogging allows users to comment in limited characters, tagging allows for personalized web experiences and collaborative writing allows for knowledge building which transgresses time and physical space. While the World Wide Web is continuously expanding, new social technologies are allowing for increased authorship through co-authorship, freedom in terms of the ability to freely voice oneself, and individual responses through collaborative experiences. (Golder and Huberman) Changes will occur in terms of mainstream traditional forms of publishing, knowledge acquisition and authorship, but it is the Internet user who is leading the changes through technological demands and adaptation of new technologies which reflect in a practical application manner, the needs of current Internet users.

References:

Alexander, B. (2006) “Web 2.0: A new wave of innovation for teaching and learning?” Retrieved from: http://www.educause.edu/EDUCAUSE+Review/EDUCAUSEReviewMagazineVolume41/Web20ANewWaveofInnovationforTe/158042

Alexander, B. (2008) “Web 2.0 and emergent multiliteracies” Retrieved from: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/content~db=all?content=10.1080/00405840801992371

Gentle, A. (2009) Conversation and Community: The social web for documentation” Retrieved from: http://pegmulligan.com/2009/11/28/book-review-conversation-and-community-by-anne-gentle/

Golder, S., and Huberman, B. (2005) The structure of collaborative tagging systems. Retrieved from: http://www.hpl.hp.com/research/idl/papers/tags/tags.pdf

Hayes, T., and Xun, G. (2008) The effects of computer-supported collaborative learning on students’ writing performance. Retrieved from: http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1599852&dl=GUIDE&coll=GUIDE&CFID=64333662&CFTOKEN=24459724

Rogers, G. (2009) “Coming soon: Google’s micro-blogging search engine.” Retrieved from: http://blogs.zdnet.com/Google/?p=1450

Wikipedia: Social media. Retrieved from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_media

Wiki: UBC. Accessed at: http://wiki.ubc.ca/Main_Page

Image taken from: http://ibat.org/files/featured/techlounge3.jpg

December 1, 2009 1 Comment

Order Amidst Disorder: How will our children find their way?

Order amidst Disorder: How will our children find their way?

Commentary #3 Delphine Williams Young

ETEC 540 University of British Columbia

November 29, 2009

“Technological devices and systems shape our culture and the environment, alter patterns of human activity, and influence who we are and how we live. In short, we make and use a lot of stuff-and stuff matters” (Kaplan, 2004, p. xiii).There is no doubt that the evolution of various types of technologies throughout the ages have always impacted the socialization of each generation of children. Whilst Plato cautioned about the technology of writing possessing the potential to weaken the intellectual processes used prior to its emergence, it is obvious based on the variety and abundance of technologies existing in present day society we have much more to be concerned about.

Walter Ong (1982) suggests that the technology of writing has transformed our consciousness as humans in a way that we will never be able to recapture it. Postman (1992), likewise, bemoans the difficulties children would have organizing their thoughts due to the impact of television and computer based media. The New London Group though basically in support of the positive impact the accessibility to such a wide variety could have on education, also identifies that “[a]s lifeworlds become more divergent and their boundaries more blurred, the central fact of language becomes the multiplicity of meanings and their continual intersection” (The New London Group, 1996, p. 10). Grunwald Associates conducted a research in 2003 which revealed that two million American children had their own websites. Alexander (2006), (2008) describes an even more rapid increase in writing technologies that are affordable and readily available. With such a body of information and new ways of presenting information, where is the teacher in all of this? How does she/he face the reality that confronts her with students who are already podcasting and blogging?

Brian Lamb (2007) makes the suggestion that all we need to do is to keep abreast of the new technologies emerging and use them in the classroom rather than be overly concerned about them. But we have to be concerned somewhat. If students are to be fully digitally literate, they will have to be literate in the original sense (that is to be able to read and write) then be trained to use the technology available. However, even as we attempt to do this we will find and that there are some children who will find it difficult turn back the clock to learn foundational concepts like memorizing timetables and spelling words, having been exposed to technology which gives them the answer immediately at the click of a mouse.

So while technology has diversified and transformed educational practices, Len Unsworth ( 2006) concedes that for teaching to be effective there will have to be more sophisticated planning and preparation to “scaffold” properly do that students with high interest needs. Researchers: Miller and Almon (2003) in the U.S.A., Fuchs and Al (2005) in Germany, and Eshet and Hamburger (2005) in Israel have all confirmed that technological mastery has nothing to do with deep thorough thinking. Deep thorough thinking can be accomplished through technology but this technology has to be used effectively. With every new technology that has emerged there are complaints that the earlier one had more authenticity than the newer one.

Whilst the Web 2.0 is a manifestation of where we wish to be technologically, it has to be approached with caution or we could create a generation that later on would be writing doctoral theses about getting back to the foundation of these technologies. The teacher should assess the writing spaces before sending the children to the wiki or website because the “public, community and economic life” (The New London Group, p.1) that he or she wants the children to be exposed to might not be as authentic as desired.

Despite the challenges of having a multiplicity of literacy tools and information; there are children who have been developing gradually and do not seem to have problems as others sifting through the matrix. Andrea Lunsford (2009) in a recent report on a study she carried out discovered that many students, that despite the criticisms being leveled at today’s digitally literate, write more and with richness and complexity than their counterparts in the 1980’s. She suggests that the social networking that they always involve writing and thus implying that writing is becoming a habit among them. But we still have to look seriously at the upcoming generation of digital natives who are Internet surfing as much as sixteen hours per week from as young as age six. Will these youngsters be able to sift all the material that they interface with? Thus, I end with a call that as educators, we become intimately involved so that we will be able to pass on the basics which will assist the young in understanding the quality of work and critical thinking that we want them to cultivate. The Web 2.0 will not have the positive impact we want to see, according to Bryan Alexander (2008), unless educators “… revamp and extend their prior skills new literacies requisite of a Web 2.0 world.”

References

Alexander, B. (2008). Web 2.0 and Emergent Multiliteracies. Theory into Practice , 150-160.

Aphek, E. (n.d.). Digital, Highly Connected Children: Implications for Education. Retrieved November 25, 2009, from www.creativeatwork.com : http://www.creativeatwork.com/…aphek/digital-literacy

Bolter, D. J. (2001). Computers, Hypertext and the Remediation of Print. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Group, T. N. (1996). A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies. Harvard Educational Review , 60-92.

Ong, W. (1982,2002). Orality and Literacy. London and New York: Routledge.

November 30, 2009 1 Comment

Final project, Comment#3

The article “Does the brain like e-books” in our readings is relevant to my educational work since I deal exclusively with adult learners who are not “digital natives” (term after Pranskey, cited in Mabrito & Medley, 2008). A typical student in my online class has grade 12 education, and ages range from 18-65, with many students engaging in online constructivist collaborative learning using modern hypermedia for the first time. The typical student seems to have a period of adaptation which is required for them to become comfortable with the new skills needed for use of computer and Internet, and to develop independent self-learning and critical thinking skills.

The article “Does the brain like e-books” in our readings is relevant to my educational work since I deal exclusively with adult learners who are not “digital natives” (term after Pranskey, cited in Mabrito & Medley, 2008). A typical student in my online class has grade 12 education, and ages range from 18-65, with many students engaging in online constructivist collaborative learning using modern hypermedia for the first time. The typical student seems to have a period of adaptation which is required for them to become comfortable with the new skills needed for use of computer and Internet, and to develop independent self-learning and critical thinking skills.

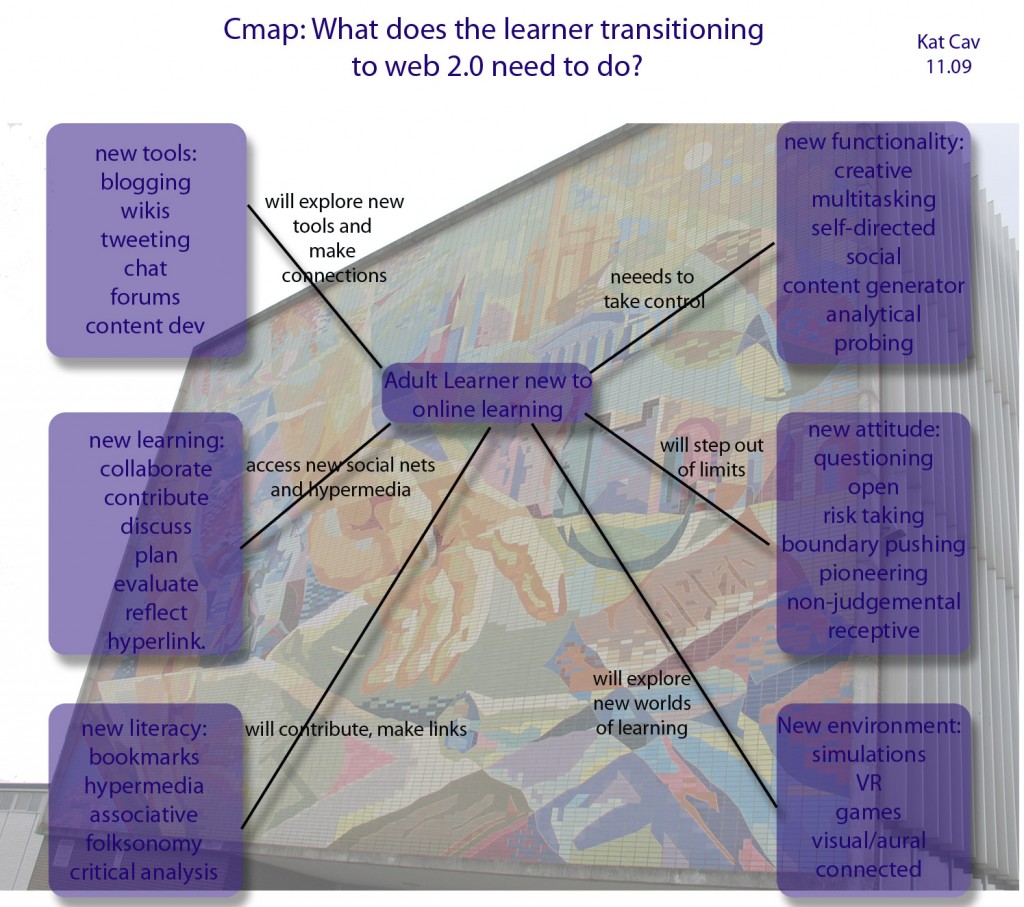

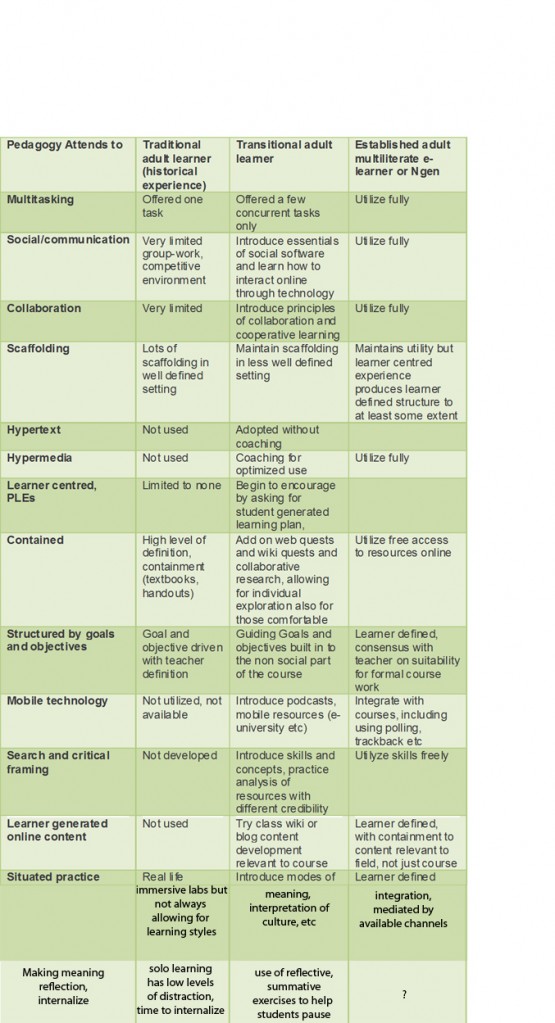

I dealt with the issue of the aspect of independent learning (learning how to learn) “the what” (after the New London Group, 1995, p 24) and its importance for students new to hypermedia in commentary #2. This commentary will focus on the learning of the content itself (the “how”, after the new London Group, 1995, p 24), and the social focus of web 2.0 learning, for students in transition between traditional literacy and learning methods, going into a web 2.0 environment. The research here will help to support or disprove my driving question of whether the transition learning period requires different pedagogy, as my daily observations seem to suggest. This subject is perhaps not as relevant for those in K-12 learning since these students are either digital natives or well versed in multiliteracy (term after the New London Group, 1996), and not faced with many first-time issues. The commentary will close with a reflective summary I developed to help understand integration of teaching initiatives outlined in the New London Group paper.

Other study groups such as Liu’s in California, the ”Transliteracies Project” (October, 2009) are shedding valuable light on this area. Liu reports “Initially, any new information medium seems to degrade reading because it disturbs the balance between focal and peripheral attention”. His observation does seem typical for newly-online learners who do in fact get sidetracked in class. Even for those adult learners with educational backgrounds, some time to adjust is required. In the MET 540 discussion forum Prizeman (2009) observes “The hypertextuality of digital writing spaced at first confused my linear mind, but now that I have spent a great deal of time interacting with them, I feel like “I’ll never go back”!” Her insight certainly reinforces the sense that there is a transitional period.

Liu (October, 2009) also concludes “It takes time and adaptation before a balance can be restored, not just in the “mentality” of the reader…but in the social systems that complete the reading environment.” This makes good sense as all literacy occurs in context, and so the student would be expected to adapt to the new way of learning in a bigger sense. Traditional pedagogy is didactic and students are used to being passive, linear and focused on one package of learning at a time as described in the Mabrito & Medley (2008) article. The Liu group confirms that in early phases of transition to new media “We suffer tunnel vision, as when reading a single page, paragraph, or even “keyword in context” without an organized sense of the whole. Or we suffer marginal distraction, as when feeds or blogrolls in the margin (”sidebar”) of a blog let the whole blogosphere in.”

The multidimensional environment calls on the learner to multitask. The open-ended resources on the Internet can be overwhelming at first as the learner enters this novel research realm. It is not the reading comprehension that suffers, as most students are adept at reading on a screen. In the “Does the Brain like e-Books?” article, Aamodt concludes, “Fifteen or 20 years ago, electronic reading also impaired comprehension compared to paper, but those differences have faded in recent studies.”

Aamodt (October, 2009) also reports that “Distractions abound online — costing time and interfering with the concentration needed to think about what you read. “ The deep concentration which is required to reflect on what is read, heard and seen may be reduced in this type of environment. Learning to focus on the work at hand and dismiss the outliers is a learning strategy that can be coached. Aamondt points out that, “Frequent task switching costs time and interferes with the concentration needed to think deeply about what you read.” Mark (October, 2009) concurs “When online, people switch activities an average of every three minutes (e.g. reading email or IM) and switch projects about every 10 and a half minutes”. That is bound to impact reflective learning. Mark also reports “My own research shows that people are continually distracted when working with digital information” so maintaining focus is confirmed to be a challenge, and her study did not just include learners new to hypermedia. She agrees with Aamondt about depth of engagement, “ It’s just not possible to engage in deep thought about a topic when we’re switching so rapidly.”

Well adapted online learners with established multiliteracy are comfortable with social networking, and multitasking in hypermedia, so more experienced learners will need more flexible environments to correlate with their skill set. Prizeman (2009) in our forums put it very well “The possibilities are endless, and the once hierarchical order that knowledge was presented in print, no longer exists in hypertext–I feel more in control of my learning, and with flexibility and freedom, I am able to search out the information that I need, as well as explore the connections between it and my world.”

The interface with online learning needs to evolve with a new appreciation of interacting with media versus human communication. Ong explores this concept and determines “communication is inter-subjective” (Ong, 2002, p 173). Ong refers to a media model of communication that focuses on informational, performance oriented interpretation, versus true communication which requires one to have advance appreciation for the other person’s inner self. That new setting is important as he points out that getting inside the minds of persons you will never know is not an easy thing to do, “but it is not impossible if you and they are familiar with the literary tradition they work in” (Ong, 2002, p. 174). Learning online does require this re-set of human communication through the window of the computer screen, and learning a new type of literary tradition, which takes time to become internalized.

Guided learning will help to address the distracting environment for transitioning students. Use of learning objectives, goal-oriented learning agreed upon by instructor and student and web or wiki quests help to direct newly-online learners to a subset of what is a large resource pool for relevant information. This limited structure is a guide not a limit. Bolter (2001, p169) points out that “relationship between the author, the text, and the world represented is made more complicated by the addition of the reader as an active participant”. A transitional learner will need to become adapted to the necessity of being more engaged and constructive when interfacing with electronic materials compared with one-way media. Use of RSS feeds can help students find key learning materials that are of high relevance. Another strategy to help a learner in that adaptation phase is to pair them with a mentor who is comfortable in web 2.0, and can be a resource for them. As well, collaborative grouping will allow students to split up a literature search or web search so that each has a self assigned area to focus in. Critical analysis of resources can be integrated with that orientation session. Some of these strategies will only be needed until new-online students’ multiliteracy is established.

The appendix table below will provide a summary of the critical pedagogy strategies that may be used to cultivate the intellect, and how they can be utilized in courses for learners of varying competence in multiliteracy.

In conclusion, it does appear that the literature supports observations that transitioning learners may need to have some early scaffolding and support and that their learning is constantly evolving through that period. Once transitioned, students can enjoy the full richness of multiliteracy and online networked learning.

A hanging issue is sparked by the observation reported by Mark (October, 2009 in “Does the Brain like e-Books?) “More and more, studies are showing how adept young people are at multitasking. But the extent to which they can deeply engage with the online material is a question for further research” Baxter (2009) mirrors these concerns when she posted “I’m not convinced that getting used to the extra activities does actually enable one to concentrate fully in spite of them. I’m more inclined to think that – along with a lot of other abilities, like amusing themselves during a power outage – the “digital generation” is losing the ability to concentrate fully on something that doesn’t engage them.”

Though these learning strategies summarized below will help us understand the transition to multiliteracy in an online learning environment, that is another realm of future enquiry; addressing the hanging issue of how transitioned students can effectively internalize and reflect on what they have learned which has been left as a question mark in the summary table.

References

Bolter, J.D. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print [2nd ed]. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

[Ed’s] Does the brain like e-books? (October 2009) featuring Liu, A., Aamodt, S, Wolf, M., Mark, G. Accessed online at the New York Times, November 1, 2009 at: from http://roomfordebate.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/10/14/does-the-brain-like-e-books

Ito, M., Horst, H., Bittani, M., Boyd, D., Herr-Stephenson, B., et al. (2008). Living and learning with new media: Summary of findings from the digital youth project. From: macfound.org , University of Southern California and the University of California, Berkeley.

Mabrito, M & Medley, R. (2008). Why Professor Johnny Can’t Read: Understanding the net generation’s texts. Innovate. Vol. 4, No. 6. Retrieved online November 1, 2009 from: http://www.innovateonline.info/index.php?view=article&id=510&action=article Page 1 of 7

New London Group (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, Vol. 66, No. 1, 60-92. Retrieved online from : http://wwwstatic.kern.org/filer/blogWrite44ManilaWebsite/paul/articles/A_Pedagogy_of_Multiliteracies_Designing_Social_Futures.htm

Ong, W. (2002) Orality and Literacy: The technologizing of the word. London: Menthuen.

Prizeman, S. (2009). From Calculator of the humanist-Miller MET ETEC 540 Forum on November 23, 2009 10:34 am.

Baxter, D. (2009). From Origin and nature of hypertext-Miller MET ETEC 540 Forum on November 27, 2009 1:18 pm

November 30, 2009 2 Comments

Learning Multiliteracies

There are approximately 5000 – 10,000 different languages in the world (Wikipedia, 2009). According to statistics from 2001 Census of Canada, the population of visible minorities living in Canada is approximately 29,639,030 out of Canada’s total population of 3,983,845 of that 1,029,395 are Chinese, 917,075 are South Africans and 198,880 are Southeast Asians(Statistics Canada, 2001). Although many are aware that Canada is a multilingual and multicultural nation, most are ignorant about the results such differences can have on society. Today’s classrooms especially in metropolitan cities consist of students of various backgrounds; however, the current traditional approaches to teaching and learning cater mostly to students’ whose mother tongue is English. The melting pot is boiling over. The current literacy education structure needs to be re-designed and re-organized in order to better prepare students for the multiliteral and diverse environments.

In the article “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures” the New London Group views that considering the multiliteracies of diverse students with various cultural backgrounds is important to teaching and learning multiliteracies for they believe “effective citizenship and productive work now require that we interact effectively using multiple languages, multiple Englishes, and communication patterns that more frequently cross cultural, community, and national boundaries” (The New London Group, 1996). Queensland’s Department of Education and Training is also advocating multiliteracies and communication media through diversity. They believe “the ability to operate in the middle world between cultures can be generated in very young learners of another language. While the experience of the so-called third place may occur through the learning of one language, it is a skill that can be transferred to dealings with other cultures in other contexts. Knowledge of the intent and tone of the language allows a true understanding of the messages in intercultural communication” (Queensland, 2004). To make intercultural communication possible the traditional four wall classroom needs to be reorganized and thought of as a borderless learning and teaching community where students can venture off to classrooms of different cultures and experiment with multiliteracies. This can be made possible with the use of various communication technologies and the analysis of various cultural texts. This valuable experience will help to equip isolated students with skills to attack real world challenges.

New London Group argues that the current literacy education system is inadequate and cannot effectively prepare students for full participation in their working, community and personal lives. We exist in an information age where information is vital to success and even survival. Even though information is more accessible than before, information is hiding behind different faces or representations. The New London Group urges that schools’ literacy curriculum be mindful to include multiliteracies closely associated with communication technology of the 21st century. According to Queensland’s Department of Education and training“multiliteracies and communications media refers to technologies of communication that use various codes for the exchange of messages, texts and information. Historically, communications media have included spoken language, writing, print and some visual media like photograph and film. Since World War II, the various electronic media such as television and other digital information technologies have provided much more complex audiovisual layers to these” (Queensland, 2004). Communication technologies alter the way people interact with information and culture. Keeping up with new communication technologies used in our information age is vital because they “change the way we use old media, enhancing and augmenting them” (Queensland, 2004) To become multiliterate “What is also required is the mastery of traditional skills and techniques, genres and texts, and their applications through new media and new technologies” (Queensland, 2004).

Multiliteracy is more than knowing how communication technologies affect information, it also includes how various texts are used together to construct meaning. Text today is blend of traditional print, visual arts and audio text. These texts do not exist in solitude. Their relationship on a page creates the overall meaning that the creator is attempting to establish. For instance, the graphs and charts that accompany a newspaper article are vital to the readers’ general understanding of the subject. The inability to read or interpret charts is the same as the inability to understand the visual images used along with written text. Decoding information from various representations to which it can be understood and analyzed requires one to have prior experience with such texts. Therefore, teaching information literacy is important in schools for such skills and capabilities will enable students to “locate, evaluate and use effectively the needed information” (Dobson & Willinksky, 2009). To do this, The New London Group emphasizes on the concept of design “as curriculum is a design for social futures, we need to introduce the notion of pedagogy as Design” as design is “the idea of Design is one that recognizes the different Available Designs of meaning, located as they are in different cultural context” because it is “through their co-engagement in Designing, people transform their relations with each other, and so transform themselves” (The New London Group, 1996). The result of the meaningful transformatin is the creation of new meanings and identities where individuals are “creator of their social futures” ( The New London Group, 1996).

The job of today’s educators is challenging because they are having to constantly learn new practices and revise learned approaches to effectively prepare young learners for the rapidly changing world. However, once learners have master the fundamentals of multiliteracies they will be able to explore and learn independently.

References:

Dobson T, Willinsky J. Digital Literacy. In: Olson D, Torrance N, editors. Cambridge Handbook on Literacy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2009. Retrieved the November 24, 2009 from: http://pkp.sfu.ca/files/Digital%20Literacy.pdf

Multiliteracies and Communications Media. Queensland Government: Department of Education and Training. Retrieved on November 25, 2009 from http://education.qld.gov.au/corporate/newbasics/html/curric-org/comm.html.

New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60-92. Retrieved, November 25, 2009, from http://newlearningonline.com/~newlearn/wp-content/uploads/2009/03/multiliteracies_her_vol_66_1996.pdf

Wikipedia. Retrieved on November 25, 2009. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lists_of_languages

Statistics Canada. Retrieved on November 24, 2009. Retrieved from http://www12.statcan.ca/english/profil01/CP01/Details/Page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=PR&Code1=01&Geo2=PR&Code2=01&Data=Count&SearchText=Canada&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&Custom=.

November 30, 2009 1 Comment

From one literacy, to many, to one

There is no question that for students in the K-12 system in North America the ‘new’ literacies afforded by digital technologies play an integral role in their lives. The question is what role they should play in schools. Most of these students have never known a time without the Internet and have not had to do research when Google (circa 1998) and Wikipedia (2001) were not options. The question of whether these new tools for finding information and the skills required to use them1 are literacy is moot for these students. It is a question posed by those attempting to make sense of a rapid change in the learning styles and methods of their students—and in that sense it is necessary and useful. However, any consideration of new literacies as ‘lesser’ literacies entirely misses the point. The new literacies of what Bolter (2001) repeatedly terms “the late age of print” are additive in nature. That is, though there is much debate about the relative merits of various forms of representation, the effect is evolutionary and cumulative rather than revolutionary and exclusionary. Many literacies co-exist, supplement one another, extend into one another, and borrow and trade metaphors. As Dobson and Willinsky (2009) note, “…the paradox [is] that while digital literacy constitutes an entirely new medium for reading and writing, it is but a further extension of what writing first made of language” (p. 1). Certainly, for K-12 students, ‘new’ literacies are not new, they are simply literacy. Thus, multiliteracy, new literacy, digital literacy and information literacy, while useful concepts in the effort to problematize and deconstruct the changes, are all facets of one, evolving and growing literacy. Writing in 1996, the year many students currently in the eighth grade were born, the New London Group argued that “…literacy pedagogy now must account for the burgeoning variety of text forms associated with information and multimedia technologies” (p. 2). Whether accounted for or not, those forms and technologies are taken for granted by most students. It seems likely that ignoring this results in a type of cognitive dissonance for students which may make it more difficult for them to learn in classrooms in which print literacy is still the dominant, if not the only, mode. A danger, however, as Dobson and Willinsky (2009) note, is the tendency to assume that “…adolescents’ competence with new technologies—is often inappropriately reconstrued as incompetence with print-based literacies” (p. 11). Some technology enthusiasts, notable among them Marc Prensky, call for a wholesale shift from print to digital literacy.

Prensky has gone so far as to claim that “…it is very likely that our students’ brains have physically changed—and are different from ours—as a result of how they grew up” (Prensky, 2001, p. 1) and their immersion in digital technologies. While there has been some interesting research in recent years on brain plasticity, particularly with reference to interactions with technology, Prensky is justly criticized for going beyond the scientific evidence (McKenzie, 2007). Yet he does highlight important characteristics of the way students now learn and socialize2 using technology. Similarly, Prensky’s classification of parents and teachers as Digital Immigrants, and their children and students as Digital Natives, though overly simplistic is not entirely unhelpful in conceptualizing the current situation in classrooms. As with other immigrants, some adults have a more difficult time adapting to a new culture than do their children who have been raised in that culture. Of course, the situation is not as black and white as Prensky would have us believe. It is also sometimes true that adults who have made the choice to emigrate, and have done the research and made the sacrifices necessary to act on that choice, are more knowledgeable and participate to a higher degree than do their children who take the advantages and freedoms of the new country for granted. It is normal to find students today who have high

speed Internet access at home, access to a family desktop computer or a desktop, laptop or netbook computer of their own, a cellular telephone (capable of texting and taking photos and short movies), and an iPod or other MP3 player. In fact, the preceding is almost a list of standard equipment for a teenager in early 21st Century North America. And while it is still true that many schools do not encourage the use of most of these technologies in the classroom, an interesting phenomenon can be observed when teachers make an attempt to do so. The teacher, likely a Digital Immigrant in Prensky’s terms, has made some study of the technology to determine the ways in which it can be most usefully employed in pursuit of particular curricular objectives. What often becomes clear is that many of the Digital Native students, who appear quite facile with technology to the casual observer, are both a.) using only limited aspects of technology primarily for social purposes (MSN, Facebook, Twitter, etc.); and, b.) not fully comprehending the implications of the uses they do make of the technology. This is particularly evident with regard to services such as Facebook where it is not uncommon to find that students rely on default privacy settings, do not read the contract they agree to when opening an account which states that all material posted to the site becomes the property of Facebook, and do not consider the potential long-term consequences of statements or images they post. In short, students are not only taking the technologies and literacies for granted, they have little or no explicit understanding of them. What this argues for is again something that was anticipated by the New London Group thirteen years ago: the need for teachers and students to come together in a learning community to which both parties bring their knowledge, experience, learning styles and literacies.

To be relevant, learning processes need to recruit, rather than attempt to ignore and erase, the different subjectivities, interests, intentions, commitments, and purposes that students bring to learning. Curriculum now needs to mesh with different subjectivities, and with their attendant languages, discourses and registers, and use these as a resource for learning. (New London Group, 1996, p. 11)

Dobson and Willinsky (2009) hit exactly the right “Whiggish” note in the closing remarks to their draft chapter on digital literacy: “We must attend to where exactly and by what means digital literacy can be said to be furthering, or impeding, educational and democratic, as well as creative and literary, ends” (Dobson and Willinsky, 2009, p. 22). It is clear that the result of this attention must be an expansion of the definition of literacy to include many aspects made possible by its digital evolution.

Notes

up1 Dobson and Willinsky (2009) point out that literacy in the digital age includes the skills, often defined as information literacy, “… not just for decoding text, but for locating texts and establishing the relationship among them” (p. 19).

up2 “Social software constitutes a fairly substantial answer to the question of how digital literacy differs from and extends the work of print literacy” (Dobson and Willinsky, 2009, p. 21).

References

Bolter, J.D. (2001). Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Dobson, T. and Willinsky, J. (2009). Digital Literacy. From draft version of a chapter for The Cambridge Handbook on Literacy.

McKenzie, J. (2007). Digital Nativism, Digital Delusions, and Digital Deprivation. From Now On, 17(2). Available: http://fno.org/nov07/nativism.html

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. On the Horizon. NCB University Press, 9(5).

November 29, 2009 1 Comment

Web 2.0 tools: educational friend or foe?

Commentary #3 ~ K. Kerrigan

After reading Bryan Alexander’s article, “Web 2.0 A New Wave of Innovation for Teaching and Learning? (2006), my assumption that I was a teacher who was “with the times” came suddenly crashing down. Alexander gives even a modest techie a run-down on what Web 2.0 can now offer. As a teacher, one must ask: are these tools an educational friend or foe? Within the classroom, the importance of using Web 2.0 tools, such as social networking, has a mixed reaction among educational professionals. Walling (2009) points to two different camps in education, those who think that social networking is a distraction to the education process, and those who see this tool as way to exchange ideas and enhance the education process. Motteram and Sharma (2009) discuss that by using Web 2.0 tools it allows students to be social in many sorts of ways: textually, orally, visually, and aurally. For example, podcasting, weblogs, wikis, Skype, Google Docs, and chat programs like MSN Messenger. “The process of creating Web 2.0 materials involves the engagement of a community, consisting of developers who create tools and the users who produce the content using a range of digital technologies” (Motteram & Sharma, 2009, p. 88). Current debate is whether those users should be students within a classroom.

Why would a teacher want to use these tools?

Alexander states that “ …Openness remains a hallmark of [the Web 2.0] emergent movement, both ideologically and technologically” (Alexander, 2006, p.34). For today’s students, this openness is an easy task, whereas for teachers and parents it is a bit harder to grasp. This open, social environment can be conducive to learning with the right teacher and the right tools. “Tech-savvy teachers who work with students to produce media will find that openness to exploring Web 2.0 strategies for idea networking and creative sharing can be highly productive” (Walling, 2009, p. 23). One might argue that it shouldn’t just be those ‘tech-savvy teachers’ who utilize these resources. Are other students and entire schools missing out on Web 2.0 and what it has to offer? For benefit of all students, it will require for some teachers to move away from their technophobia and worries about the constant sharing of information.

Motteram and Sharma (2009) state that “…when we stop seeing such technologies as somehow extras and when they blend into the background, they will have become as accepted as books are now, as a part of the classroom furniture” (p. 86).Teachers must first look at the inherent value of these tools and the effect it will have on their students. Web 2.0 responds more deeply to its users versus Web 1.0. As Motteram and Sharma (2009) declare, “Web 1.0 tools deliver information to people, Web 2.0 tools allow the active creation of information by users” (p. 88). Students are a lot more social today with the utilization of these tools. For many, it is almost second nature to blog, bookmark, or tag something for themselves and for their peer community to view. Within the classroom these tools, especially social networking sites, create a new and exciting environment for the students. “It enables the face-to-face class to be extended in various kinds of ways and also extends the time that the students spend on tasks” (Motteram & Sharma, 2009, p. 90). Students are also encouraged to be more collaborative within this environment. This can be accomplished by using wikis or weblogs. As Alexander reminds us that “these services offer an alternative platform for peer editing, supporting the now-traditional elements of computer-mediated writing-asynchronous writing…” (2006, p.38). Editing, reading, and writing are affected when a student uses one of these tools. When they realize that their peers are going to be reading their work (via a weblog or wiki), many students create work surpassing that done within the f2f classroom. The changing face of literacy in today’s classroom also allows for the student to become the author, the producer and the critic of text. They are now active learners with these technologies, rather than passive consumers of text (Handsfield, Dean & Cielocha, 2009). Having students who are active learners, who are passionate about literacy, and who want to post their work, means that the teacher can spend more time supporting and encouraging their students rather than fighting them on basic assignments.

In short, Web 2.0 tools need to be embraced by all teachers within the classroom. It will not only enhance their curriculum, but excite and motivate all students. Web 2.0 tools are friend to the teacher and ultimately the student, offering a plethora of resources and opportunity for collaboration among peers globally.

References

Alexander, B. (2006). A New Wave of Innovation for Teaching and Learning?. Educause Review, 41(2), 32-44.

Cox, E. (2009). The Collaborative Mind: Tools for 21st-Century Learning. MultiMedia & Internet@Schools, 16(5), 10-14. Retrieved on November 26, 2009 from Academic Search Complete database.

Handsfield, L., Dean, T., & Cielocha, K. (2009). Becoming Critical Consumers and Producers of Text: Teaching Literacy with Web 1.0 and Web 2.0. Reading Teacher, 63(1), 40-50. Retrieved on November 26, 2009 from Academic Search Complete database.

Motteram, G., & Sharma, P. (2009). Blending Learning in a Web 2.0 World. International Journal of Emerging Technologies & Society, 7(2), 83-96. Retrieved on November 26, 2009 from Academic Search Complete database.

Walling, D. (2009). Idea Networking and Creative Sharing. TechTrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning, 53(6), 22-23. Retreived on November 26, 2009 from doi:10.1007/s11528-009-0339-x.

November 29, 2009 2 Comments

Multi-literacy and assessment

Commentary # 3, Cecilia Tagliapietra

Along this course, we’ve discussed the “creation” or discovery of text and how it has transformed throughout the ages; providing mankind a way of expressing thoughts and feelings. In this third and last commentary, I’d like to discuss how we’ve become literate in different areas and how literacy, as text, has also been transformed to fit new manifestations of text. I’d also like to touch upon the challenges we face as teachers, to assess and impulse the development of these competencies or literacies.

As text has transformed spaces and human consciousness (Ong, 1982, p. 78), we’ve also changed the meaning of the term literacy, integrating not only the focus on text as the main aspect of it, but also the representations, and methods in which text is manifests, as well as the meaning given or understood according to different contexts. The New London Group (1996) has introduced the term “multiliteracies” for the “burgeoning variety of text forms associated with information and multimedia technologies” (p. 60). From this understanding and meaning, we can identify different literacy abilities or competencies. The two most important types of literacies we’ll narrow down to are: digital literacy and information literacy.

Dobson and Willinsky (2009) assertively express that “digital literacy constitutes an entirely new medium for reading and writing, it is but a further extension of what writing first made of language” (referring to the transformation of human consciousness, (Ong, 1982, p. 78)). These authors consider digital literacy an evolution that integrates and expands on previous literacy concepts and processes, as Bolter expresses “Each medium seems to follow this pattern of borrowing and refashioning other media” (Bolter, 2001, pg. 25). With digital literacy, we can clearly identify previous structures and elements shaping into new, globalized and closely related contexts.

Digital technologies have recently forced us to change and expand what we understand as literacy. Being digitally literate is being able to look for, understand, evaluate and create information within the different manifestations of text in non-physical or digital media. Information literacy is also closely linked to the concept of digital literacy. According to the American Association of School Librarians (1998), an information literate, should: access information efficiently and effectively, evaluate information critically and competently, use the information accurately and creatively. We can clearly see an interrelationship between the concepts of these literacies; they both rely on an interpretation of text and an effective use of this interpretation. The development of critical thinking skills is also closely related to these concepts and the ability to use information (and text) creatively and accurately.

The use of these new literacies has also changed (and continues to do so) the way we communicate and learn; we constantly interact with multimedia and rapidly changing information. Even relationships and authority “positions” are restructured, as consumers also become producers of knowledge and text. With the introduction and use of these new literacies, education has somehow been “forced” to integrate these competencies into the curriculum and, most importantly, into the daily teaching and learning phenomena.

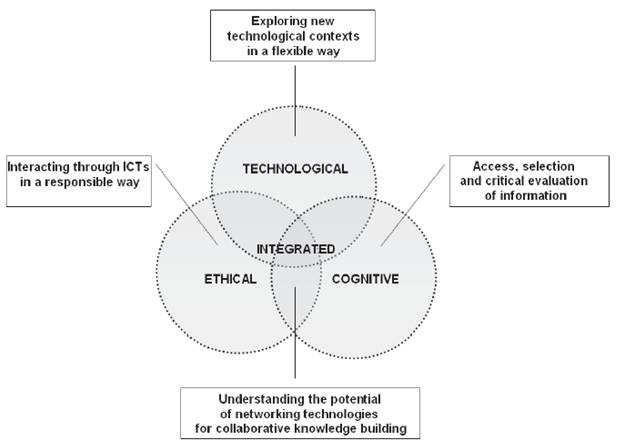

As teachers, we are not only required to facilitate learning in math, science, etc.; we are also required to facilitate and encourage the development of these literacies as well as critical thinking skills. Teaching and assessing these abilities is no easy task, as it’s not always manifested in a concrete product. Calvani and co-authors (Calvani, et.al, 2008), propose an integral assessment for these new competencies, involving the technological, cognitive and ethical aspects of the literacies (See Figure 1). In order to assess, we must initially transform our daily practices to integrate these abilities for our students and for ourselves. Being literate (in the “normal” concept) is not an option anymore. We are bombarded with and have access to massive amounts of information which we need to disseminate, analyze and choose carefully. Digital and information literacies are needed competencies to successfully understand and interpret the globalized context and be able to integrate ourselves into it.

Learning (ourselves) and teaching others to be literate or multi-literate is an important task at hand. Tapscott (1997) has mentioned that the NET generation is multitasker, digitally competent and a creative learner. As educators and learning facilitators, we also need to integrate and develop these competencies within our contexts.

Literacy has transformed and integrated different concepts and competencies, what it will mean or integrate in five years or a decade?

Figure 1: Digital Competence Framework (Calvani, et.al, 2008, pg. 187)

References:

American Association of School Librarians/ Association for Educational Communications and Technology. (1998) Information literacy standards for student learning. Standards and Indicators. Retrieved November 28, 2009 from: http://www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/aasl/guidelinesandstandards/informationpower/InformationLiteracyStandards_final.pdf

Calvani, A. et. al (2008) Models and Instruments for Assessing Digital Competence at School. Journal of e-Learning and Knowledge Society. Vol. 4, n. 3, September 2008 (pp. 183 – 193). Retrieved November 28, 2009 from: http://je-lks.maieutiche.economia.unitn.it/en/08_03/ap_calvani.pdf

Dobson and Willinsky’s (2009) chapter “Digital Literacy.” Submitted draft version of a chapter for The Cambridge Handbook on Literacy.

New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60-92. Retrieved, November 28, 2009, from http://newlearningonline.com/~newlearn/wp-content/uploads/2009/03/multiliteracies_her_vol_66_1996.pdf

Tapscott, Don. Growing Up Digital: The Rise of the Net Generation, Retrieved November 28, 2009 from: http://www.ncsu.edu/meridian/jan98/feat_6/digital.html

November 29, 2009 1 Comment

Social Tagging

Third Commentary by Dilip Verma

Social Tagging

Many popular web based applications are described as belonging to the Web 2.0. Alexander (2008) suggests that what defines Web 2.0 software is that it permits social networking, microcontent and social filtering. Users participate in the Web 2.0 by making small contributions that they link to the works of other contributors to form part of a participative discourse based on sharing. In social filtering, “creators comment on other’s creations, allowing readers to triangulate between primary and secondary sources.” (Alexander, 2008). One of the offspring of this new cooperative form of literacy is the creation of Folksonomies.

Folksonomies are user-defined vocabularies used as metadata for the classification of Web 2.0 content. Users and producers voluntarily add key words to their microcontent. There are no restrictions on these tags, though programs often make suggestions by showing the most commonly previously used tags. Folksonomies (also known as ethnoclassification) represent an important break with the traditional forms of information classification systems. This technology is still in its infancy; presently it is used for the categorizing of photos in Flickr, of Web pages in Del.icio.us and of blog content in Technorati. However, its use is sure to spread as the Web 2.0 gains popularity.

Berner- Lee, designed the Web to allow people to share documents using standard protocols. His proposal for the Semantic Web (see video) is that raw data should now be made shareable both between web programs and between users. At the moment social tagging is program specific. There is no reason to assume that it will or should remain this way. For tags to be readable by different programs, they will require a common structure. A system whereby tags can be shared and analyzed across applications is possible by creating an ontology of tags. This ontology will merely be a standard of metadata that records more than just the tag word applied to an object. Gruber (2007) proposes a structure for the metadata including information on the tag, the tagger, and the source. In this way tags will be transferable and searchable across the Web, making them a much more powerful technology.

Standard classification systems are structured from the top down. Professionals carefully break down knowledge into categories and build a vocabulary, which can then be used to hierarchically categorize information. Traditionally, categorizing is a labor-intensive, highly skilled process reserved for professionals. It also requires users to buy into a culturally defined way of knowing. Social tagging is the creation of metadata not by professionals (e.g. librarians or catalogers), but by the authors and users of microcontent. The tags are used both as an individual form of organizing as well as for sharing the microcontent within a community (Mathes, 2004).

Weinberger (2007) divides organizational systems into three orders, defining the third order as a system where information is digital and metadata is added by users rather than professionals. Apart from the physical advantages of storing information digitally, the author sees that this change in the creation of metadata will “undermine some of our most deeply ingrained ways of thinking about the world and our knowledge of it.” Weinberger (2007) sees tagging as empowering, as it lets users define meaning by forming their own relationships rather than having categories imposed upon them. “It is changing how we think the world itself is organized and -perhaps more important- who we think has the authority to tell us so.” (Weinberger,2007, ¶ 48). Mathes notes that “the users of a system are negotiating the meaning of the terms in the Folksonomy, whether purposefully or not, through their individual choices of tags to describe documents for themselves” (2004, ¶ 46). In Folksonomies, the creation of meaning lies firmly on the shoulders of the user.

The interesting thing about social tagging is that a consensus of meaning is naturally formed. “As contributors tag, they have access to tags from other readers, which often influence their own choice of tags” (Alexander, 2008, p. 154). Udell notes that “the real power emerges when you expand the scope to include all items, from all users, that match your tag. Again, that view might not be what you expected. In that case, you can adapt to the group norm, keep your tag in a bid to influence the group norm, or both” (2004, ¶ 5). Folksonomies are organic as they develop naturally through voluntary contributions. Traditionally, society defines the “set of appropriate criteria” by which things may be categorized (Weinberger, 2007, ¶ 6). But Folksonomies should allow us “to get rid of the idea that there’s a best way of organizing the world” (Weinberger, 2007, ¶ 7).

However, Boyd raises some concerns about who is forming this consensus and its influence on power relations. The author notes that “most of the people tagging things have some form of shared cultural understandings” (2005, ¶ 3) and that these people are ” very homogenous” (2005, ¶ 3). The author adds that “we must think through issues of legitimacy and power. How are our collective choices enforcing hegemonic uses of language that may marginalize?” (2005, ¶ 7). At the moment the use of tags is restricted to a small homogenous group. This is representative of the wider problem of the globalizing influence of a web dominated by “a celebration of the “Californian ideology”” (Boshier & Chia, 1999). The consensus formed in Folksonomies will be representative of only a small sector of the population. To address this requires providing access and a voice in the Web 2.0 discourse to minorities. If user defined tags become the standard for metadata on the Web 2.0, it is important that all groups take part in the forming of the consensus. Without access for marginalized communities, Folksonomies will not achieve their true liberating potential.

References

Alexander, B. (2008). Web 2.0 and Emergent Multiliteracies. Theory into Practice, 47(2), 150-160. Retrieved November 20, 2009 from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00405840801992371

Boyd, D. (2005). Issues of Culture in Ethnoclassification/Folksonomy. Retrieved November 26, 2009, from Corante Web Site: http://www.corante.com/cgi-bin/mt/teriore.fcgi/1829

Boshier, R. & Chia, M. O.(1999) Discursive Constructions Of Web Learning And Education: “World Wide” And “Open?” Proceedings of the Pan-Commonwealth Forum on Open Learning Retrieved November 15 from http://www.col.org/forum/PCFpapers/PostWork/boshier.pdf

Gruber, T. (2007). Ontology of Folksonomy: A Mash-up of Apples and Oranges. Int’l Journal on Semantic Web & Information Systems, 3(2). Retrieved November 27, 2009 from http://tomgruber.org/writing/ontology-of-folksonomy.htm

Mathes, A. (2004). Folksonomies-Cooperative Classification and Communication Through Shared Metadata. Retrieved November 26, 2009 from http://www.adammathes.com/academic/computer-mediated-communication/folksonomies.html

Udell, J. (2004). Collaborative Knowledge Gardening. Retrieved November 25, 2009, from InfoWorld Web Site: http://www.infoworld.com/d/developer-world/collaborative-knowledge-gardening-020

Weinberger, D. (2007). Everything Is Miscellaneous: The Power of the New Digital Disorder. New York: Times Books. Retrieved November 26, 2009 from http://www.everythingismiscellaneous.com/wp-content/samples/eim-sample-chapter1.html

November 29, 2009 3 Comments

Commentary # 3

Is Web 2.0 Selling out the Younger Generation?

Commentary # 3

By David Berljawsky

Submitted to Prof. Miller

Nov 29, 2009

There is one underlying theme that involves technology and text education that I need to touch upon. Are we sabotaging the upcoming generation with the way that we teach technology? Or is it the opposite and we are actually giving them the proper tools to succeed? It is possible that in the shift to modern web 2.0 technologies we are neglecting to educate about the simplest things that we take for granted? This can include key knowledge’s such as social skills, communication and even basic literacy? Students are engaged in the web 2.0 process like never before. These technologies are creative based and offer the user a newfound ability to edit and modify information to fit into their respective wants and needs. According to Alexander “In American K-12 education, students increasingly accept these kinds of technology-driven information structures and the literacies that flow from them (Alexander, P.2).” To me this quote acts as a double edged sword. Students are engaged in the new literacies (web 2.0) like never before, but are these new literacies appropriate and conducive to meeting proper educational standards? Or do they simply aid in creating an individualist society that is lacking a sense of community? This paper will examine some of the positive and negative aspects that occur when Web 2.0 is taught without providing the proper scaffolding. This commentary will examine its potential consequences both socially and educationally.

One needs to examine the benefits of these technologies and understand their positive influences before one can criticize them. According to the New London Group, in its article “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures, “As a result, the meaning of literacy pedagogy has changed. Local diversity and global connectedness mean not only that there can be no standard; they also mean that the most important skill students need to learn is to negotiate regional; ethnic, or class-based dialects… (New London, P.8).” This melds together education, literacy and even community in a newfound manner. It is a mix-up or mash-up of sorts. Students are required, due to the changing landscape of the world and technology to concentrate on learning communication skills with other cultures in an online environment. One would assume that this is a positive and worthwhile endeavour to achieve towards. However, this can increase the creation of a more macro centered community. This will only increase the affects of globalization and prevent local communities from prospering and expressing themselves.