Making Connections

Personal Connections– Learning

Four years ago I suffered an injury that tore one of the tendons that controls movement in my thumb. I eventually regained use of the thumb and was able to perform all daily activities with little trouble. All except one. It was difficult and very painful to write. So I turned to using the computer. I bought myself a laptop and thankfully my part-time job was a fully computerized environment. At first I saw it as a very efficient substitute writing tool; it was much quicker to type than to jot down notes. About half a year later I began to feel that learning was becoming more difficult, and causing more fatigue, and my creativity had been highly impacted.

It wasn’t until I took this course that I began to really investigate the relationship between the two.

In thinking about the definition of text and looking at the evolution of writing spaces and technologies made me reflect on my current and previous modes of learning. Earlier notes were meticulously underlined, highlighted, written in different colours (while also possible on the computer, rarely used these functions because I owned a black and white laser printer). The handwriting was all over the page, with little clumps of information, connected by arrows and diagrams. The margins were reserved for ‘outside links’, where I made personal connections and devised memory aids to help me synthesize and remember information and ideas. This practice also extended to any papers, textbooks, and novels that I read. However, the injury discouraged this and I ended up typing a few notes on the computer (instead of directly on the page—which made the information feel … disconnected).

Remediation

The concept of remediation was also very useful in my understanding of the difficulties with embracing technological use in schools. As a TOC I visited many schools and saw many classrooms wherein the computer lab was used for typing lessons, KidPix, or research. Many schools also have Interactive White Boards (IWBs), and teachers use them as, in essence, a very cool replacement for a worksheet. Remediation helps frame and pinpoint the reason for this phenomenon: the use of technology is not just a set of skills, it’s a change in thinking and pedagogy. Literacy is not just literacy anymore, it has become multiliteracies and Literacy 2.0. Teachers cannot continue to teach reading and writing the same way as before, because text is not the same anymore.

December 22, 2009 No Comments

Storage and Performance

I attempted to work through how technologies’ characteristics of storage and performance affect fluency. It represents a start. Please follow this link to see my attempt.

December 6, 2009 No Comments

Connections

In trying to make some final connections between my own research on Graphic Novels, increased literacy and multimodal texts, I read a few of the projects that seemed most relevant to me. What follows are my thoughts. (Just pretend the italicized words are my thought bubbles.)

I just want to remind myself to consult Drew Murphy’s Wiki on using Digital storytelling for the reluctant reader. It might be an interesting contrast to what I did for my project.

http://wiki.ubc.ca/User:DrewRyan#Creating_Classroom_Community_Through_Digital_Storytelling

I turned out his project was more about engaging students in storytelling using digital media, rather than getting them to read more. I think that would be an excellent next step to promoting reading with graphic novels and other types of visual media. As I thought when I read the title, this is an excellent example of a further remediation of text. As Bolter describes it, one technology building on the other. In the same way, the skills learned using multimodal texts allow the reader to progress onto the next, more sophisticated media. The use of digital texts also allows even more input and creativity from the writer (consumer as producer).

This quote from Noah Burdett: “With the need for speed a literate person needs to be able to think critically about the material in terms of its relevance and its authority.” NoahBurdett_ETEC540_majorproject https://blogs.ubc.ca/etec540sept09/2009/11/30/final-project-literacy-and-critical-thinking/

“To become multiliterate “What is also required is the mastery of traditional skills and techniques, genres and texts, and their applications through new media and new technologies” (Queensland, 2004). “from Learning Multiliteracies by Carmen Chan

Philip Salembier discussed the New Literacy and Multiliteracies in From one literacy, to many, to one.

He really explains how we have to be prepared as teachers and parents to understand that literacy means more than reading and writing and that digital literacy is not just understanding how to navigate the internet. All of these are aspects of the new literacy, along with social networking skills.

Fun interactive story http://wiki.ubc.ca/Course:ETEC540/2009WT1/Assignments/MajorProject/ItsUpToYou by Ryan Bartlett. Might use this style to get the seniors to do a research project on Social Injustice.

Finally, just because this one blew me away! From Tracy Gidinski https://blogs.ubc.ca/etec540sept09/2009/11/29/the-holocaust-and-points-of-view/ I hope I can use this style at some point either with my Marketing or International Business class or perhaps even a simpler storyline for an FSL course.

December 2, 2009 No Comments

Final Project – Graphic Novels, Improving Literacy

Before I started this course, I had noticed the increased availability of graphic novels in our school library. My teenage son is a fan, preferring Manga to the North American style comic books. When our school recently began school-wide silent reading to promote literacy, student interest in and requests for graphic novels increased further. There seemed a clear link between this form of literature and the need to improve literacy rates as part of our province’s Student Success initiatives.

In the past weeks, I researched the topic of graphic novels to find the link between improved literacy and an alternate form of literature. This website is meant to be an informative document. My hope is to link it to the school website for parents to find documented answers to their questions about how to get reluctant readers engaged in regular reading.

A website is unlike a traditional essay in that I found it difficult to conclude the document. You will find both internal and external links. Typical of websites, the readers can choose the path to follow – it was never meant to be linear. Ultimately, I hope this site encourages readers to continue their own journey in learning about graphic novels.

November 28, 2009 1 Comment

Commentary 2 – Literacy

Literacy n. 1 the ability to read and write. 2 competence is some field of knowledge, technology, etc. (computer literacy; economic literacy) (Oxford Canadian Dictionary, 1998, pg. 836)

Literacy has been discussed and will continue to be a topic of discussion far into the human future. The need to learn and to facilitate learning and the economic drivers that push technology changes will impact learning and how we view and define literacy. Ong states that “Literacy began with writing but, at a later stage of course, also involves print”. (1982, pg. 2) One would assume that literacy would and should develop to become multifaceted to include all information and communication techniques and the social factors that influence those modes. As the identified by the Oxford Canadian Dictionary, literacy should imply an understanding, along with the ability to read and write.

In the article A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures, The New London Group presents the concept of multiliteracies – a redesigned ‘literacy’ with mutual consideration for “the multiplicity of communications channels and media, and the increasing saliency of cultural and linguistic diversity.” (1996, pg. 4) The new globalization, with ever increasing diversity, has resulted in an encroaching on the workplace, in public spaces and in our personal lives. These influences are driving a demand for a language “needed to make meaning” (1996, pg. 5) of our economic and cultural exchanges. How we perceive and how others perceive us is a factor in success. This success impacts and affects all facts of our lives. But in a global village, can we ensure that success is attained by all. It would appear to me that the requirement for multiliteracy is needed mostly in areas of economic disadvantage and disparity. Where access to even “mere literacy” (New London Group, pg. 4) is limited.

Cross-cultural communications and the negotiated dialogue of different languages and discourses can be a basis for worker participation, access, and creativity, for the formation of locally sensitive and globally extensive networks that closely relate organizations to their clients or suppliers, and structures of motivation in which people feel that there different backgrounds and experiences are genuinely valued. (New London Group, 1996, pg. 7)

To increase cross-cultural experiences within the workers’ education, the use of facilitated online study circles are excellent venues to create a dialogue for success and facilitate the “making of meaning” in workers’ participation. The International Federation of Workers’ Education Associations (IFWEA) employs study circles to attempt to close the gap in both worker education and multiliteracy in disadvantaged groups. These educational events provide an opportunity for Study Circle members to engage in the four elements of pedagogy as described including: Situated Practice; Overt Instruction; Critical Framing; and Transformed Practice. (New London Group, pg. 5)

The division of pedagogy into “the how”, places a new role and responsibility on the teacher and the school. In the articles, the teacher is described as a facilitator of cultural differences, and a developer of critical thinkers. This individual must navigate not only the knowledge of required instructional content, but also the technical and the cultural. The school, as the organization tasked to make differences out of homogeneity (The New London Group, pg. 11) must now reconfigure the classroom to include both global and local content and relationships, flavoured by diverse cultural distinctions. “Local diversity and global connectedness mean not only that there can be no standard; they also mean that the most important skill students need to learn is to negotiate regional, ethnic, or class-based dialects”. (The New London Group, pg. 8

While the New London Group article was written in 1996, it was bold to address some of the utopian ideals within education and literacy; individualized education at both a local and global level, with no standards and a high regard for cultural and linguistic differences in the classroom. Sadly, literacy is influenced by the very diversity and globalization that is forcing most of our social changes. These changes can be best described using the very words of described by the authors; “Fast Capitalism” (pg. 10); “rigorously exclusive” (pg.6); and “market driven” (pg.6). As Dobson and Willinsky states “a gender gap still persists in many parts of the world, being wider in some countries”. (2009, pg. 12) This gap may be an indicator “that in certain respects there has been very little movement in the gender gap in the last two decades”. (pg. 13) Perhaps with such disparities in our global context, the goal of our educational organizations and facilitators should be to ensure that a standard is met with regards to information literacy- “ the ability to locate, evaluate, and use effectively the needed information” (Dobson & Willinsky, 2009, pg. 18) This would ensure that a “competence is some field of knowledge, technology, etc.” (Oxford Canadian Dictionary) is achieved.

References:

Dobson, T. & Willinsky, J. (2009). Digital Literacy. Submitted to The Cambridge Handbook on Literacy

International Federation of Workers’ Educational Association. (unknown). The international programs. Retreived online 10 Nov 2009 from the World Wide Web: http://www.wea.org.uk/Education/International/

New London Group. (1996). A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies. Designing Social Futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60-92.

Ong, Walter (1982). Orality and literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. London: Methuen.

Oxford Canadian Dictionary. (1998). Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

November 14, 2009 1 Comment

RipMixFeed using del.icio.us

For the RipMixFeed activity I collected a set of resources using the social bookmarking tool del.icio.us. Many of us have already used this application in other courses to create a class repository of resources or to keep track of links relevant to our research projects. What I like about this tool is that the user can collect all of their favourite links, annotate them and then easily search them according to the tagged words that they created. This truly goes beyond the limitations of web browser links.

For this activity I focused on finding resources specifically related to digital and visual literacy and multiliteracies. To do this I conducted web searches as well as searches of other del.icio.us user’s links. As there are so many resources – too many for me to adequately peruse – I have subscribed to the tag ‘digitalliteracy’ in del.icio.us so I connect with others tagging related information. You can find my del.icio.us page at: http://delicious.com/nattyg

Use the tags ‘Module4’ and ‘ETEC540’ to find the selected links or just search using ETEC540 to find all on my links related to this course.

A couple of resources that I want to highlight are:

- Roland Barthes: Understanding Text (Learning Object)

Essentially this is a self-directed learning module on Roland Barthes ideas on semiotics. The section on Readerly and Writerly Texts is particularly relevant to our discussions on printed and electronic texts. - Howard Rheingold on Digital Literacies

Rheingold states that a lot people are not aware of what digital literacy is. He briefly discusses five different literacies needed today. Many of these skills are not taught in schools so he poses the question how do we teach these skills? - New Literacy: Document Design & Visual Literacy for the Digital Age Videos

University of Maryland University College faculty, David Taylor created a five part video series on digital literacy. For convenience sake here is one Part II where he discusses the shift to the ‘new literacy’. Toward the end of the video, Taylor (2008) makes an interesting statement that “today’s literacy means being capable of producing fewer words, not more”. This made me think of Bolter’s (2001) notion of the “breakout of the visual” and the shift from textual to visual ways of knowing.

Alexander (2006) suggests that social bookmarking can work to support “collaborative information discovery” (p. 36). I have no people in my Network as of yet. I think it would be valuable to connect with some of my MET colleagues so if you would like share del.icio.us links let’s connect! My username is nattyg.

References

Alexander, B. (2006). Web 2.0: A new wave for teaching and learning? Educause Review, Mar/Apr, 33-44.

Bolter, J.D. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext and the remediation of print. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Taylor, D. (2008). The new literacy: document design and visual literacy for the digital age: Part II. Retrieved November 13, 2009, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RmEoRislkFc

November 14, 2009 2 Comments

Lost and Found in the Digital Age

By connecting through Web 2.0 tools and sharing information online, it is easy to create links to new people. However, even small bits of information you share may tell others (globally) more about you than you may think.

In September of this year, Evan Ratliff, reporter for Wired Magazine tried to disappear for a month. But as we leave digital footprints of our personal information, it becomes harder and harder to hide ourselves. Once information is online it is difficult, if not impossible to erase. This is why information literacy (as part of digital literacy) is such an important component of education today.

Check out the short ABC news clip: How to Disappear in the Digital Age. The story made me stop and think twice about all of our public collaborative spaces and who may run across them. In Evan Ratliff’s instance, people were encouraged to tracked him down. However I think the example shows that locating someone with an online presence can be quite easy.

Best,

Natalie

November 13, 2009 No Comments

How word processors and beyond may be changing literacy

Commentary #2

The word processor, in combination with the computer disk and CRT monitor, was first introduced in 1977 (Kunde, 1986). As Bolter points out “the word processor is not so much a tool for writing, as it is a tool for typography (p. 9).” It seems that, even today, the word processor is essentially used as a tool to mimic conventional methods of typing. Whereas older printing processes lock “the type in an absolutely rigid position in the chase, locking the chase firmly onto a press,” a word processor only differs in that it composes text “on a computer terminal” in “electronic patterns (letters) previously programmed into the computer (Ong, p. 119).” Bolter notes this by stating “most writers have enthusiastically accepted the word processor precisely because it does not challenge their conventional notion of writing. The word processor is an aid for making perfect printed copy: the goal is still ink on paper (p. 9).” The word processor helps better facilitate the processes that were once done on the typewriter. That is, writers still type in text letter by letter, but the computer greatly improves revision. A few of these improvements include copying/cutting and paste, changing fonts and paper size, and inserting automatically updating table of contents, outlines, references. It is “in using these facilities, the writer is thinking and writing in terms of verbal units or topics, whose meaning transcends their constituent words (Bolter, p. 29).” In this regard, the word processor did not change the printed word. However, although the word processor did not fundamentally change how a printed product looks, it did have a major impact on industry and business and on literacy in education.

In the early 1980s there was much focus on the difference word processors were making in industry, business, and scholarly work. Bergman points out that “this electronic revolution in the office [word processing] may change who does what sort of work, create some jobs and eliminate others (p. F3).” In fact, in 1977 5.8% of jobs offered in the New York Times mentioned computer literacy skills such as word processing, this number doubled by 1983 (Compaine, p. 136). This was especially evident in clerical positions in which “the proportion of secretary/typist want ads that required word processing skills went from zero in 1977 to 15 percent in 1982 (Compaine, p. 136).” Furthermore, Word processors, coupled with a phone line greatly increased the speed that documents were sent and received. Instead of mailing or dictating documents to another person, documents including graphs and charts could now be written and transmitted, in seconds, over the telephone, more cheaply than previous methods (Bencivenga, p. 11). Scholars “with the help of a computer programmed to scan the text quickly, picking out passages that contain the same word used in different contexts (Compaine, p. 137).” In the early 1980s Word processors and computers fundamentally changed how we process information and thus had much impact on literacy. Compaine refers “to computer skills as additional to, not replacements (p.139)” to literacy and that “whatever comes about will not replace existing skills, but supplement them (p. 141).” Compaine’s essay was written in 1983, but this trend continues today.

Furthermore, the word processor has affected literacy amongst students. In 1983 Ron Truman published an article in The Globe and Mail in which he reported that elementary teachers said word processors were “having a remarkable effect on how children learn to use language: writing on a computer screen improves spelling, grammar and syntax (p. CL14).” An article by Goldberg et al. entitled “The effect of computers on student writing: A meta-analysis of studies from 1992 to 2002″ summarizes that thirty-five previous studies concluded that the “writing process [in regards to K–ı2 students writing with computers vs. paper-and-pencil] is more collaborative, iterative, and social in computer classrooms as compared with paper-and-pencil” and that “computers should be used to help students develop writing skills . . . that, on average, students who use computers when learning to write are not only more engaged and motivated in their writing, but they produce written work that is of greater length and higher quality (p. 1).” Similarly, Beck and Fetherston conclude that “The use of the word processor promoted students’ motivation to write, engaged the students in editing, assisted proof-reading, and the students produced longer texts” and “produced writing that was better using the word processor than that which was achieved using the traditional paper and pencil method (p. 159).”

Different forms of electronic writing have participated “in the restructuring of our whole economy of writing (Bolter, p. 23).” Even as early as 1983, Compaine predicted that in respect to electronic texts, “many adults would today recoil in horror at the thought of losing the feel and portability of printed volumes . . . print is no longer the only rooster in the barnyard (p. 132).” Looking at present day and into the future, the computer continues to reshape and challenge the traditional form of the printed book: “our culture is using the computer to refashion the printed book, which, as the most recent dominant technology, is the one most open to challenge (Bolter, p. 23).” The World Wide Web and most recently the advent of web 2.0 have challenged traditional writing media and the way in which we create electronic media. Word processors have become one tool in an arsenal of programs developed for electronic publishing (such as Dreamweaver for web development, PowerPoint for presentations, iMovie and Movie Maker, and Adobe Flash for animations). As such, literacy still includes traditional texts, but much has been added with digital literacy. Books, magazines, newspapers, academic journals, etc. predominately written using a word processor (or another desktop publishing software), in their traditional form will not be replaced in the near future, but they have certainly had to give up much of their dominance to non-traditional, electronic, writing spaces.

John

References

Barbara R. Bergmann (1982, May 30). A Threat Ahead From Word Processor. The New York Times. p. F3.

Beck, N., & Fetherston, T. (2003). The effects of incorporating a word processor into a year three writing program. Information Technology in Childhood Education Annual, 2003 (1), 139 – 161. Retrieved January 15, 2009, from http://www.editlib.org/index.cfm/files/paper_17765.pdf?fuseaction=Reader.DownloadFullText&paper_id=17765.

Bencivenga, Jim (1980, March 28). Word processors faster than dictation. The Christian Science Monitor. p. 11.

Bolter, Jay David. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print [2nd edition]. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Compaine, Benjamin, M. (1983). The New Literacy. Daedalus, 112(1), pp. 129-142.

Goldberg, A., Russell, M., & Cook, A. (2003). The effect of computers on student writing: A meta- analysis of studies from 1992 to 2002. Journal of Technology, Learning, and Assessment, 2(1). Retrieved November 7, 2009, from http://escholarship.bc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1007&context=jtla

Johnson, Sharon. (1981, October 11). Word Processors Spell Out A New Role for Clerical Staff. New York Times, p. SM28.

Kunde, Brian. (1986). A Brief History of Word Processing (Through 1986). Fleabonnet Press. Retrieved November 7, 2009 from http://www.stanford.edu/~bkunde/fb-press/articles/wdprhist.html

Ong, Walter, J. (1982). Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. London and New York: Methuen.

Truman, Ron. (1983, November 24). Word processors prove boon in making youngsters literate. The Globe and Mail. p. CL.14.

November 8, 2009 1 Comment

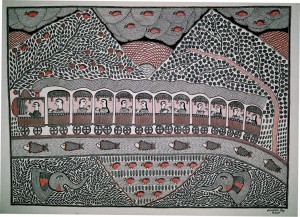

Mithila Art as a Communication Technology

Long before there were computers in most of our homes, there was Mithila Art in homes of what is now India and Nepal. Originally, this folk art form mainly consisted of lively murals painted on the walls of homes in rural villages. But it was much more than simple art for art’s sake. “Mithila painting is part decoration, part social commentary, recording the lives of rural women in a society where reading and writing are reserved for high-caste men” (Arminton, Bindloss & Mayhew, 2006, p. 315). This was art that gave a voice to powerless rural women as a communication technology.

Long before there were computers in most of our homes, there was Mithila Art in homes of what is now India and Nepal. Originally, this folk art form mainly consisted of lively murals painted on the walls of homes in rural villages. But it was much more than simple art for art’s sake. “Mithila painting is part decoration, part social commentary, recording the lives of rural women in a society where reading and writing are reserved for high-caste men” (Arminton, Bindloss & Mayhew, 2006, p. 315). This was art that gave a voice to powerless rural women as a communication technology.

Historical and Cultural Context

This art form acquired its name from the kingdom of Mithila where it originated around the seventh century A.D. At that time, the region was a vast plane located primarily in what is now eastern India as well as in southern Nepal. However, the cultural center and capital of the region was in what is now the city of Janakpur, Nepal only 20 kilometers from the Indian boarder. Janakpur is of course the home of Janakpur painting while the town of Madubandi, India is home of paintings of the same name. Mithila art consists of both kinds of paintings of which Madubandi are more common.

It is said that Mithila art was born when King Janak commissioned artists to create paintings at the time of the marriage of his daughter, Sita, to the god Lord Ram. This might have to do with the fact that most Madubani paintings are created during festivals celebrating marriages and births, religious and social events and ceremonies of the Maithil community. Others say that, “Its original inspiration emerged out of the local women’s craving for religiousness and an intense desire to be one with god” (Janakpur Women’s Development Center, n.d.). However it actually began is not clear, but what it became after being passed down through many generations surly is.

“Mithila is a wonderful land where art and scholarship, laukika and Vedic traditions flourished together in complete harmony between the two” (Mishra, 2009, 4). This harmony was uncommon during this time in many other regions in southern Asia as well as the rest of the world. The general attitude toward artists in this region is one of utmost respect and they were even compared with gods. That could be a major reason why women in ancient Indian society, whom were traditionally regarded as much less significant than men, adopted Mithila art as well as other art forms as not only a communication technology, but as a means for empowerment as well.

“Picture writing is perhaps constructed culturally (even today) as closer to the reader, because it does not depend upon the intermediary of spoken language and seems to reproduce places and events directly” (Bolter, 2001, p. 59). The murals were originally painted during important community events as a kind of subjective snapshot as well as social commentary. This was a positive way for rural women to have a voice and to be heard.

Implications for Literacy and Education

In a communicative context, ‘literacy’ is commonly defined as “the ability to read and write” where to ‘write’ is defined as to “mark (letters, words, or other symbols) on a surface, with a pen, pencil, or similar implement” (Oxford University Press, 2009). So although most Mithila artists were not literate in phonetic writing, they were exceptionally literate in picture writing. As with oral communication, this type of literacy served to bring people together and strengthen their communities. “As we look back through thousands of years of phonetic literacy, the appeal of traditional picture writing is its promise of immediacy. By the standard of phonetic writing, however, picture writing lacks narrative power” (Bolter, 2001, p. 59). The “narrative power” of which Bolter refers to, is the ability of phonetic writing to convey detailed information from a first person perspective. Unfortunately, this ability also has a tendency to actually distance those in communication rather than bring them together as in picture writing.

Bolter goes on to write that, “Sometimes, particularly when the picture text is a narrative, the elements seem to aim for the specificity of language. Sometimes, these same elements move back into a world of pure form and become shapes that we admire for their visual economy” (2001, p. 63). This explains the duality of this art form as both a communication technology and an aesthetic art form. Another perspective of visual communication technologies is that, “Display is, in respect to its prominence and significance and ubiquity, the analogue of narrative” (Kress, 2005, p.14). So while Mithila paintings perhaps lacked the ability to convey a first person narrative, they narrowed the gap between the composer and her audience in a beautiful visual mode of communication.

For the Maithil artists, the ability to express their desires, dreams, expectations, hopes and aspirations to their community in (picture) writing through their painting was most likely much more valuable than communicating detailed information to outsiders by means of phonetic writing. “Unlike words, depictions are full of meaning: they are always specific. So on the one hand there is a finite stock of words—vague, general, nearly empty of meaning; on the other hand there is a n infinitely large potential of depictions—precise, specific, and full of meaning” (Kress, 2005, pgs.15-16). The meaning they conveyed through their art was unmistakable and accessible to all. In this case, picture writing literacy did not lead to phonetic or alphabetic writing literacy. It did, however, require education.

As all writing is communication technology, Mithal art required education to master the particular tools, materials and techniques of this unique style of picture writing. Most of these artists were not formally educated and were illiterate in the ways of phonetic reading and writing. But they did have to learn about the range of natural hues that could be derived from preparations and combinations of clay, bark, flowers and berries as well as how to fashion brushes from bamboo twigs and small pieces of cloth (Mishra, 2009).

Conclusion

Although Mithila art did not directly lead ancient India to a conventional sense of literacy nor to formal education of the masses, it did give a voice to the voiceless. As a communication technology, it provided something for those artists that was and remains a critical element of their society: a heightened consciousness. As Ong writes, “Technologies are not mere exterior aids but also interior transformations of consciousness, and never more than when they affect the word. Such transformations can be uplifting. Writing heightens consciousness” (2002, p. 81).

Mithila art still exists today, but unfortunately has been commercialized with the introduction of tourism. Much of what this art form and communication technology was and did for these people has been lost. Most pieces are painted on paper and many are of scenes made-to-order that have nothing to do with Maithil culture, although selling their artwork has proved an increasing source of income and has in turn improved their quality of live. With the support and guidance development organizations, groups are now promoting the consumption of Vitamin A, voting, safe sex, and saying “no” to drugs to their communities (Janakpur Women’s Development Center, n.d.). So although it has changed considerably over many generations, Mithila art is still a meaningful communication technology.

References

Armington, S., Bindloss, J., & Meyhew, B. (2006). Lonely Planet: Nepal. Oakland, CA: Lonely Planet

Bolter, D. (2001). Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Janakpur Women’s Development Center. (n.d.). Retrieved October 3, 2009, from http://web.mac.com/nadjagrimm/iWeb/JWDC/Welcome.html

Kress, G. (2005). Gains and losses: New forms of text, knowledge, and learning. Computers and Composition, 22, 5-22. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science

Mishra, K. K. (2009). Mithila Paintings: Past, Present and Future. Retrieved October 4, 2009 from Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. Web site: http://ignca.nic.in/

Mithila Art – Madhubani Painting and Beyond. (n.d.). Retrieved October 3, 2009, from http://mithilaart.com/default.aspx

Ong, W. J. (2002). Orality and Literacy. New York: Routledge

Oxford University Press. (2009). Ask Oxford. Retrieved October 10th, 2009 from http://www.askoxford.com/

November 2, 2009 1 Comment

Orality and Mythology

In Orality and Literacy, Walter Ong (2002) drew a distinction between cultures characterized by literacy and cultures characterized by “primary orality”, the latter being comprised of “persons totally unfamiliar with writing” (p. 6). By accepting a form of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, the view that a culture’s language determines the way in which its members experience the world, Ong also considered these two types of culture to be two types of consciousness, or “modes of thought” (Ibid, p. 6). While Ong attempted to address how literate culture developed from “oral cultures”– i.e. cultures characterized by primary orality (Ibid, p. 31) – the sharp distinction he drew between the two respective types of consciousness involved in these types of culture makes the question of how this development would have been possible particularly troublesome (Dobson, Lamb, & Miller, 2009).

Ong evidently recognized that there can be what might be called “transitional forms” between primary orality and literacy. He noted that oral cultures in the strict sense hardly existed anymore (Ong, 2002, p. 11), suggesting that cultures may be oral to a large degree even when they have been somewhat influenced by literate cultures. Furthermore, he granted that literate cultures may still bear some of the characteristics of the oral cultures from which they developed, possessing what he called “oral residue” (Ibid, p. 40-1). However, by characterizing literate and oral modes of thought as he did, it is not clear how it could even be possible for the former to arise out of the latter– although it is clear that they must have done so.

One of the main difficulties lies in Ong’s characterization of oral modes of thought as less “abstract” than literate modes. He asserted that all conceptual thought is abstract to some degree, meaning that concepts are capable of referring to many individual objects but are not themselves individual objects (Ibid, p. 49). According to this view, concepts can be abstract to varying degrees depending on how many individual objects they are capable of referring to. The concept “vegetation” is able to refer to all the objects the concept “tree” can and still more, and thus it is a more abstract concept. The oral mode of thought, Ong asserted, utilizes concepts that are less abstract and this makes it closer to “concrete” individual objects.

This notion of concepts being “abstract” is relatively recent, being developed mainly by the philosopher John Locke (1632-1704). In ancient and mediaeval thought, the distinction between the concept “tree” and this tree or that tree would be described as a distinction between a universal and a particular. Locke’s view that universals are “abstract” ideas was based on the theory that they are formed by the mind’s taking away or “abstracting” that which is common to many particulars (Locke, 1991, p. 147). For example, the concept “red” is formed by noticing many red objects and then “abstracting” the common characteristic of redness from all of the other characteristics the objects possess.

A problem with this theory of abstraction as a general explanation of how concepts are formed was pointed out by Ernst Cassirer (1874-1945). Cassirer noted that the theory first of all claims that it is necessary to possess abstract concepts in order to apprehend the world as consisting of kinds of things, and that without them we would only have what William James – and Ong after him (Ong, 2002, p. 102) – called the “big, blooming, buzzing confusion” of sense perception. The theory also claims that to form an abstract concept in the first place it is necessary to notice a common property shared by a number of particular objects. Yet according to the first claim we couldn’t notice this common property if we didn’t already have an abstract concept. We wouldn’t notice that several objects share the property of redness if we didn’t already have the concept “red” (Cassirer, 1946, p. 24-5).

Cassirer’s criticism of abstraction as a theory of concept formation could serve as a particularly valuable corrective to Ong’s account of the distinction between orality and literacy. Cassirer himself offered a similar account of two modes of thinking which he called “mythological” and “discursive”. The “mythological” mode of thought resembled Ong’s “oral” mode in many ways. Like Ong’s oral mode of thought it was a mode of thought closely linked to the apprehension of objects as they stood in relation to practical activity (Ong, 2002, p. 49; Cassirer, 1946, p. 37-8). Also like the oral mode of thought it was associated with the notion that words held magical power, as opposed to the view of words as mere arbitrary signs (Ong, 2002, p. 32-3; Cassirer, 1946, p. 44-5, 61-2).

If Walter Ong’s account of orality and literacy could be synthesized with Cassirer’s distinction between the mythological and the discursive, it would benefit in that the latter is capable of describing a development from one mode of thought to the other without posing the problematic view that this involves increasing degrees of abstraction. The development of the mythological mode into the discursive mode is not the move away from a concrete world of perception to an abstract world of conception, but the move from the use of one kind of symbolic form to the use of another type. Furthermore, as the mythological mode of thought is already fully symbolic it is possible to study this mode of thought by studying the symbolism used in mythological cultures. While the stages of development from the mythological to the discursive described by Cassirer (e.g. perceiving objects as possessing “mana”, seeing objects as appearances of “momentary gods”, polytheistic forms of thinking, and so on) may not be supported by empirical evidence, the kind of analysis that is offered by his theory of “symbolic forms” makes the type of development in question conceivable and provides us with a program for studying it.

References

Cassirer, E. (1946). Language and Myth. (S.K. Langer, Trans.). New York: Dover. (Original work published 1925).

Dobson, T., Lamb, B., & Miller, J. (2009). Module 2: From Orality to Literacy Critiquing Ong: The Problem with Technological Determinism. Retrieved from https://www.vista.ubc.ca/webct/urw/lc5116011.tp0/cobaltMainFrame.dowebct

Locke, John (1991). An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. In M. Adler (Ed.), Great Books of the Western World (Vol. 33). Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica. (Original work published 1698).

Ong, W. J. (2002). Orality and Literacy. New York: Routledge.

October 4, 2009 2 Comments