Book production, throughout western civilization has been closely associated with the social pillars of modern society. Two key shifts in the economies of production have been the transition to codex and subsequently print. These shifts have had a profound impact on vast sections of life, such as religion, law, education, commerce, arts, exploration, and industry. The way, in which these technology shifts achieved this, is of course, complex. Some of the principal factors will be briefly highlighted in this paper.

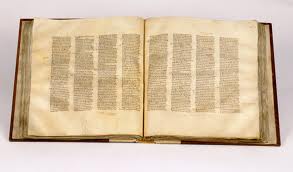

This first move towards the recognizable book known today began to evolve in the first century. It was precipitated by the Roman innovation of a type of notebook using folded, rather than rolled, parchment (Grout, 2002). With a protective wooden cover added, the first codex was in use by the end of the first century AD (Grout, 2002). The production of the codex increased efficiency, was easy to store, and could accommodate longer or multiple texts. Although the convenience of this hand held technology may have be recognized by accountants, traders, travelers, and poets, it was the Christian church that made the codex a cultural, and certainly religious, icon.

Over the next few hundred years, Christianity moved from a loose sect towards establishing a major world religion. As such, Christianity sought to distinguish itself from Jewish and pagan script, and the codex was a major part of this (Kearney, 2009). It was not only able to capacitate the longer Gospels, but could do so in a single volume for easy reference for early priests.

Part of this distinction of Christianity involved an intimate association with reading text. According to Kearney (2009), “Christianity consistently defined and redefined itself by invoking internal and external threats to the proper reading of scripture and world” (p.34). One of the difficulties in defining itself as a world religion laid in the fact that Christiani incorporated sacred texts of Judaism. Providing a different understanding of these texts was partially represented by the adoption of the codex as a Christian icon.

The ensuing Middle Ages was an era dominated by Christian thought in the west propagating the use of the codex. Book production was held in monasteries where monks doubled as scribes. Education at this time was aimed at developing literacy for the sole purpose to study religious books. Further, memorization of these books was encouraged, while analysis and interpretation was not. Still, the codex as a tool of promoting Christianity to the mass population was very effective, even if there was only a single interpretation permitted. “It (codex) was a development in the history of the book as monumental as the invention of printing a thousand years later” (Grout, 2002, para. 17). However, as influential it was to Christianity and society, I am not sure there is the evidence to support this statement.

The codex with its close association to Christianity was significant, to be sure. But, Elizabeth Eisenstein (1979) observes in the Printing Press as an Agent of Change,

as long as texts could be duplicated only by hand, perpetuation of the classical heritage rested precariously on the shifting requirements of local elites. Texts imported into one region depleted supplies in others; the enrichment of certain fields of study by an infusion of ancient learning impoverished other fields of study by diverting scribal labor. (p. 159)

Simply, it was the remarkable increase in book production enabled by the press that restored classical thought and disseminated current thought throughout Europe. The widened literary diet subsequent to the invention of the press allowed scholars for the first time to study classic Greek and Roman literature as a complete cultural system causing people to reconsider preconceived notions. The story of how information and knowledge then sparked the enlightenment and Italian Renaissance has been often told. The specific story of how it would change the nature of education is less known.

By the time of Gutenberg’s press, the rise of universities was already on the way. The volume of books that came on the market in this century would demand new skills from these academics. Not since the existence of the Alexandrian library was there a need to categorize information to this degree. Prior to print, collections were not well-ordered, with uncertain origin and labels, and no agreed conventions for chronology, geography, nomenclature, and orthography (Eisenstein, 1979). Slowly, the emphasis on the memorization of declarative knowledge would give way to the more important information management skills of research and cross referencing. Literates were now able to check multiple sources in one subject matter. These new categories of information would form the subject disciplines, which represent distinct ways of thinking about the world (Gardner, 2007) With the massive increase of specific findings widely documented in print, academics could systematically develop investigatory techniques. The scientific practices of research, analysis, observation, and reporting in one field of study created a deeper understanding. This is noted in disciplines from art to astronomy as very little change is made before the fifteenth century (Eisenstein, 1974). Since print, and increasingly now with digital text, the ability to survey vast amounts of information, and organize it is a useful way for interpretation and the construction of new theory has become the crucial skill for students.

Guttenberg’s invention in the 15 century was unlike any other in terms of its consequences to European civilization. It is after this pivotal period when a new technology is able to serve a community of learning dispersed in Italy and throughout Europe that we find significant social change. A major question of this course has been how this change should occur. Can it be driven by human thought or must it always follow the demands of new technologies introduced in society? Without knowing exactly how innovation will alter our way of life, people will not be comfortable in reforming education to meet this moving target. This is a question, however, educators must address: what will be the skills necessary for young people after the digitalization of text? Even if we do not know for sure, what we have learned from the shift from scroll to codex, and manuscript to print, is that society will be much different and people will need to be able to navigate a massive volume of information in order to make sense of it.

References

Eisenstein, E. L. (1979). The printing press as an agent of change: Communications and cultural transformations in early-modern Europe Volume 1. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Gardner, H. (2007). Five minds for the future. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing.

Kearney, J. J. (2009). The incarnate text: Imagining the book in reformation England. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Grout, J. (Ed.). (2002). Scroll and codex. In Encylopaedia Romana. Retrieved from: http://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/notaepage.html

Press (photograph) Retrieved October 30, 2010 from http://blossomingwhereiamplanted.blogspot.com/

Codex (photograph) Retrieved October 30, 2010 from http://chattahbox.com/world/2009/07/06/codex-sinaiticus-oldest-bible-in-the-world-scanned-from-animal-skins-published-online/

Your piece is well written and easy to follow. Interesting comments about the significance of Gutenberg’s press, however, I do think he was supported by wealthy towns people who had made money by trading and banking, by skilled labourers and by all the centuries of scribes who had gone before. Not quite a one man show.

Laura

Hi Chris – Interesting subject matter. I was especially informed by the section on the codex, which I hadn’t understood before in terms of the mechanics of creating a multi-use book with manuscript instead of print. The potential for having side-by-side texts for comparison and commentary is a breakthrough in technology that must have taken hundreds of years of labour to perfect using hand-manufacturing and scribes for rendering volumes of texts. Nicely done in bringing the element of editorial standardization into what was an existing technology—the codex book— in your section on the printing revolution.