“Oukyo’s Ghost,” painted by Hounen Tsukioka in 1882, depicts another painter, Maruyama Oukyo, and his reaction to a painting. Tsukioka was expressing the power of image on the human psyche and the ability for text and image to “come alive” and interact with the viewer. This is an example of ekphrasis not only because it is a depiction of an artist by an artist and of a painting within a painting, but because it shows the 19th century shift in the genre of ekphrasis which began to use the reaction of the viewer as part of the description (Munsterburg, 2009). This shift or addition to the meaning of ekphrasis is an important one as it is one of the concepts that digital ekphrasis is founded upon: the interaction between the image and the viewer.

Early Ekphrasis

Ekphrasis, also or previously known as ecphrasis, claims its origins from the Greek language as “ex” and “phrazein,” the literal translation being “out” and “speak.” In ancient cultures, with few methods of publication, ekphrasis meant the verbal recollection or description of an object. One of the earliest recorded explanations of ekphrasis is in Plato’s (376 BC), Republic, Book X, where he uses the example of a bed and discusses the concept of “bedness” as an analogy for exphrasis. A bed is defined as an object and bedness refers to all the different forms a bed can take depending on the angle it is looked at and how it is reconstructed or replicated.

Plato philosophizes that there are three possible creators of a bed: 1) God, who created the one and only original bed which exists in nature (which can be understood to be the idea, the prototype or the original realization of a bed or the need of a bed), 2) the carpenter, the maker of the physical or the real bed, and 3) the painter, who superimposes an image of the real bed onto the canvas (or whatever is being drawn on). Through Plato’s analogy of bed and bedness, ekphrasis can be understood to be the imitation of a previously established creative idea or art form by its representation or re-creation as another art form.

Plato concludes his discussion of bedness and ekphrasis with the question: “Which is the art of painting designed to be– an imitation of things as they are, or as they appear– of appearance or of reality?” The question still echoes more than two millennia after Plato first pondered it. The answer may exist somewhere in our modern day multimedia, somewhere amongst real life captured in images, amongst the books and stories that have become films, amongst the song lyrics that have become music videos or amongst real people that have become avatars, human personalities represented as digital characters superimposed onto real-time, interactive virtual spaces. Or we may be further lost, needing more than ever to ask, are the images we see reality, or an imitation of reality?

Ekphrasis and Literature

In ancient times, ekphrasis referred to art, mainly paintings and sculptures directly inspired from objects, people and situations in real life. Later, with the spread of print forms such as books, ekphrasis was mainly a concept that occurred in literature. Several examples of ekphrasis are found in Oscar Wilde’s (1890), The Picture of Dorian Gray. The narcissistic main character, Dorian Gray, possesses a magical self-portrait of himself. Wilde’s literal description of the painting, what it looks like and how it has supernatural powers to preserve human youth, is an example of literary ekphrasis: “This portrait would be to him the most magical of mirrors. As it had revealed to him his own body so it would reveal to him his own soul… he would keep the glamour of his boyhood. Not one blossom of his loveliness would ever fade. Not one pulse of his life would ever weaken. Like the gods of the Greeks…” (Wilde: 136). Literature practices ekphrasis when it is able to waken and involve our visual imagination through the mere written words on the page.

Another example of ekphrasis from this gothic horror story is through the description of Dorian’s lover, Sybil Vane. Sybil, who commits suicide when she believes Dorian no longer loves her, is compared to many of the tragic heroines of Shakespeare’s plays: “Sybil Vane represented to you all the heroines of romance, that she was Desdemona one night, and Ophelia the other; that if she died as Juliet, she came to life as Imogen… The girl never really lived, and so she has never really died… Mourn for Ophelia, if you like. Put ashes on your head because Cordelia was strangled. Cry out against Heaven because the daughter of Brabantio died. But don’t waste your tears over Sybil Vane. She was less real than they are” (Wilde: 132). As seen in Wilde’s writing, ekphrasis can exist in a fictitious character by description of another fictitious character. Wilde plays on the words of life and death though his characters and his characters’ impersonation of other characters, virtually inviting the readers to ask who is real and who is not.

Before the digital age, it can be seen that ekphrasis prominently existed as a literary description of an art form, or a literary imitation of another literary form. Literary ekphrasis reflected a time of plain literacy, meaning “a focus on letters” (Dobson and Willinksky: 15). Images were brought to Wilde’s readers not through images on paper, but through letters on paper. The shift from letter focus to digital focus, however, again shifted and expanded the meaning of ekphrasis.

Ekphrasis in the Digital Age

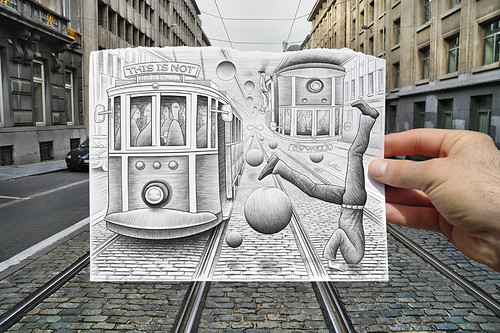

With the creation of multimedia forms, such as television and computers, the phenomena of ekphrasis exploded. With the breakout of visual media, the definition of ekphrasis expanded to include a visual representation of the literate form, essentially, reverse-ekphrasis. Reverse-ekphrasis, the representation of words into images, is likely more prominent in digital media than the previous definition of ekphrasis, the representation of images into words. Reverse-ekphrasis has become so prominent that it is simply considered ekphrasis itself, therefore, ekphrasis may be now be defined as the description or representation of any art or text form to any other art or text form.

An example of digital ekphrasis is in a digital space such as Second Life. Digital spaces such as Second Life are imitations of real life objects (such as money represented through Linden (the creator of the site) dollars), people (represented through animated characters or avatars) and experiences that happen in real life (such as human communication and relationships that develop through text, audio and visuals/gestures). Virtual reality is an example of life superimposed onto the screen as live, multi-sensory, interactive digital art. Although there are some examples of text to art ekphrasis in virtual reality spaces, the type of ekphrasis that happens here is more similar to the type of ekphrasis that happened in Plato’s day. Ekphrasis, by Plato’s definition over two thousand years ago, meant something directly from nature (a person, place, object or situation) that was transposed into an art form, such as a sculpture or a painting. Electronic art simulations take most of their elements directly from nature (from real life, not from text or literature) and from experiences that happen in real life (not from text to image translations, not from literature-based ekphrasis).

The metamorphoses of ekphrasis that occurred with the emergence of digital technology has brought the concept of ekphrasis full circle, back to imitations of things found in nature. There now exists two prominent types of ekphrasis: representations from nature or real life, and representations of other artificial art forms, such as paintings or literature. The emergence and dominance of digital technology forces change not only to the concept of ekphrasis, but also to the concept of literacy. Literacy no longer means the ability to read letters and words, but also the ability to read images. Does this, therefore, and necessarily, force change to the concept of education?

Ekphrasis and Education; Multimodality and Multiliteracies

Literacy is “a carefully restricted project– restricted to formalized, monolingual, monocultural, and rule-governed forms of language” (Cazden, et al.: 1). Literacy, and literacy pedagogy is monomodal. In a world that flows on multimodality, there is little practicality to educators and students limiting their learning to a monoliterate education. In order to function in a multimodal world, students must learn to become multiliterate. This requires being able to find and communicate meaning is a variety of modes instead of limiting oneself to a literary mode. Multimodality is made up of much more than a linguistic mode of meaning, it incorporates visual meaning, audio meaning, gestural meaning and spatial meaning (Cazden, et al.: 19). Teaching with multimodal means will not only prepare students who live and function in a multimodal world, it will allow students who come from a variety of learning strengths to function more successfully and enjoyably in a less monoliterate-biased learning space.

Basic and primal human communication, without any print or digital technology, is both visual and verbal, in essence, it has always been multimodal (Kress: 5). By the very nature of digital media being a form of visual and audio media, ekphrasis can be thought of as a naturally occurring phenomenon within electronic communication spaces. Examples of ekphrasis are “manifestations of natural signs” (Bolter: 57), of objects and things, such as a bed, that Plato described as “existing in nature.” Images are a more natural form of communication to us than print forms such as literature or text, and the breakout of visuals in multimedia shows us that there is a human desire to communicate visually, to return to what exists in nature. Perhaps the human inclination to get closer to what exists in nature is also our human inclination to get to the truth.

The breakout of visuals in media forms shows that communication has been remediated from the written form that existed before the digital age. To the dismay of the literate ages, categorized by the dominance of imageless print, the digital age is overtaking forms of communication, attempting to bring information sharing back to a more natural form. Educators who found their success through plain literacy may project a negativity to changes that seem to challenge the written word: “The elites will continue to use writing as their preferred mode, and hence, the page in its traditional form” (Kress: 18). Education, however, as one of the most important modes of communication, must be also be remediated.

Final answer?

There is a prominence of text to image ekphrasis because image appears to be a clearer or more truthful depiction than words alone. Surely, a photograph of a bed, or a video that is able to show all angles and the seemingly true-to-life form, shape and colour of the bed would be closer to the truth and much easier to understand than a written description of that bed. In returning to Plato’s question: “Which is the art of painting designed to be– an imitation of things as they are, or as they appear– of appearance or of reality?” Perhaps Plato’s truth-seeking question is not to be answered, but to be pondered upon eternally, as we go back and forth between text and image and immerse ourselves in ekphrastic and multimodal spaces. However, there is no doubt that the answer in facing this question is to be ready as a generation that is multiliterate and adapted to multimodality.

References

Bolter, J.D. (2001). Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers: Mahwah, New Jersey.

Cazden, C., Cope, B., Fairclough, N., Gee, J. (1996). “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures.” Harvard Educational Review: 66: 1, pp. 1-31.

Dobson, T. and Willinsky, J. (2009). “Digital Literacy.” In David Olson and Nancy Torrance (Ed.), Cambridge Handbook of Literacy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kress, G. (2005). “Gains and Losses: New Forms of Text, Knowledge, and Learning.” Computers and Composition: 22, pp. 5-22.

Munsterburg, M. “Writing about Art: Ekphrasis.” Retrieved on November 20, 2010: http://www.writingaboutart.org/pages/ekphrasis.html

Plato (translated by Jowett, B.). Republic, Book X. Retrieved on November 20, 2010: http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/republic.11.x.html

Wilde, O. (2003). The Picture of Dorian Gray. London: Collector’s Library.