“Be Realistic Demand the Impossible”[1]

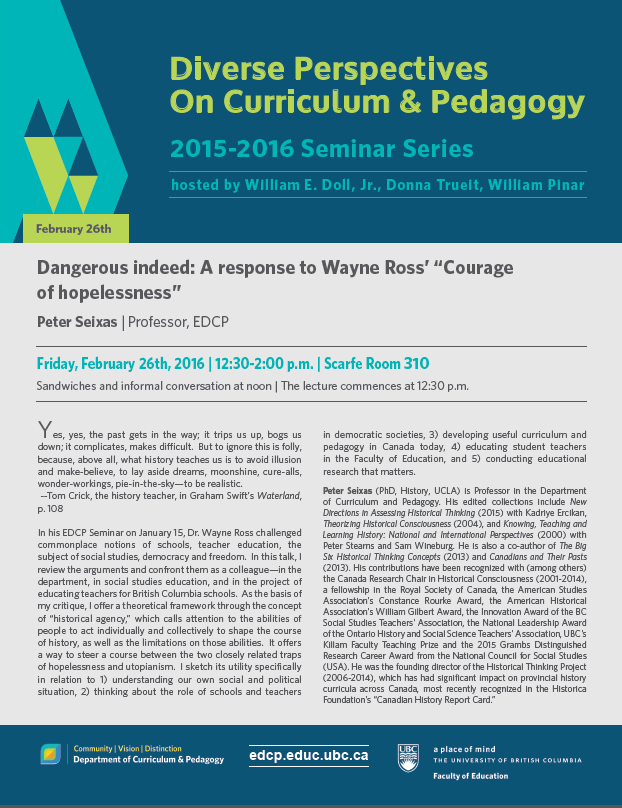

Rejoinder to Peter Siexas’s

Dangerous indeed: A response to E. Wayne Ross’ ‘Courage of hopelessness’

University of British Columbia

Department of Curriculum and Pedagogy

Seminar Series: Diverse Perspectives on Curriculum & Pedagogy

February 26, 2016

1. The “courage of hopelessness” is, perhaps ironically, an optimistic position.

The publicity blurbs for Peter’s talk stated that he would offer “a way to steer a course between the two closely related traps of hopelessness and utopianism.” This is a misreading of my use of the term “courage of hopelessness,” which is a position of some great optimism.

[Read the text of my January 15, 2016 seminar “The Courage of Hopelessness: Democratic Education in the Age of Empire.” Watch video my talk here. Watch Seixas talk, my response and Q&A with audience below.]

2. Utopia – “Be realistic demand the impossible”

We need Utopia / utopian thought more than ever because we live in a time without alternatives when neoliberal capitalism reins triumphant and uncontested.

[This circumstance is captured in Margaret Thatcher’s declarations: “There is no alternative” and “there is no such thing as society.” The latter of which was embodied in Stephen Harper’s refusal to “commit sociology,” which was an ideological attempt to prevent the identification of and responses to structural injustices that result from capitalism.]

The so-called global free market works well for the One Percent, but not for rest of humanity. In my talk, I provided some examples of the ways in which capitalism trumps democracy (pun intended).

The hegemonic system of global capitalism dominates not because people agree with it; it rules because most people are convinced “There Is No Alternative.” Indeed, as I have argued, the dominant approach to schooling and curriculum, particularly in social studies education, is aimed at indoctrinating students into this belief.

Utopian thinking allows us to consider alternatives, such as the pedagogical imaginaries which I presented in my January seminar, in attempt to open up spaces for rethinking our approaches to learning, teaching, and experiencing the world. And these imaginaries are necessary because traditional tropes of social studies curriculum (e.g., democracy, voting, democratic citizenship) are essentially lies we tell to ourselves and our students (because democracy is incompatible with capitalism; capitalist democracy creates a shallow, spectator version of democracy at best; democracy as it operates now is inseparable from empire/perpetual war and vast social inequalities).

Stephen Duncombe argues that Utopia is politically necessary even for people who do not desire an alternative society,

“Thoughtful politics depend upon debate and without someone or something to disagree with there is no meaningful dialogue, only an echo chamber…Without a vision of an alternative future, we can only look backwards nostalgically to the past, or unthinkingly maintain what we have, mired in the unholy apocalypse that is now.”

3. The Nature of Method or Inquiry

I believe the key question to be posed in social studies and one that history can help us answer is “why are things as are they are?”

[Marx’s method, dialectics, is a tool that does not necessarily require a Marxist politics or practice (class struggle), see for example the dialectical approaches of individualist libertarians Chris Sciabarra and John F. Welsh.]

What we understand about the world is determined by what the world is, who we are, and how we conduct our inquiries.

Things change. Everything in the world is changing and interacting. When studying social issues we should begin by challenging the commonsense ideas of society or particular social issues as a “thing” and consider the processes and relationships that make up what we think of as society or a social issue, which includes its history and possible futures.

Inquiries into social issues help us understand how things change and also contribute to change.

In understanding social issues and how things change it helps to “abstract” or start with “concrete reality” and break it down. Abstraction is like using camera lenses with different focal lengths: a zoom lens to bring a distant object into focus (what is the history of this?) or using a wide-angle lens to capture more of a scene (what is the social context of the issue now?)

This approach raises important questions: where does one start and what does one look for? The traditional approach to inquiry starts with small parts and attempts to establish connections with other parts leading to an understanding of the larger whole. Beginning with the whole, the system, or as much as we understand of it, and then inquiring into the part or parts of it to see how it fits and functions leads to a fuller understanding of the whole.

Analysis of present conditions is necessary, but insufficient. The problem is that reality is more than appearances and focusing on appearances, the face value of evidence from our immediate surroundings, can be misleading.

How do we think adequately about social issues, giving issues the attention and weight they deserve, without the distorting them? We can expand our notion of a social issue (or anything for that matter) to include, as aspects of what it is, both the process by which the issue has come to life and the broader interactive context in which it is found. In this way, the study of a social issue involves us in the study of its history (the preconditions and connections to the past) and the encompassing system.

Remembering, “things change,” provokes us to move beyond analyzing current conditions and historicizing social issues, to project probable or possible futures. In other words, our inquiry leads to the creation of visions of possible futures.

This process of inquiry, then, changes the way we think about a social issue in the here and now (change moves in spirals, not circles) in that we can now look for preconditions of a future in the present and use them to develop political strategies (i.e., organize for change).

4. The School and “Social Progress”

The fundamental parts of human nature include a need for creative work, for creative inquiry, for free creation without the arbitrary limiting effects of coercive institutions.

Schools are continually threatened because they are autocratic and they are autocratic because they are threatened—from within by students and critical parents and from without by various and disparate social, political, and economic interests. These conditions divide teachers from students and community and shape teachers’ attitudes, beliefs, and action.

Teachers then, are crucial to any effort to improve, reform, or revolutionize curriculum, instruction, or schools. The transformation of schools must begin with the teachers, and no program that does not include the personal and collective rehabilitation of teachers can ever overcome the passive resistance of the old order.

Schools should places that enable people to analyze and understand social problems; envision a future without those problems; and take action to bring that vision in to existence.

Social progress is enhanced when we rewrite the narrative of the triumphant individual working within the system into a story of the creation of self-critical communities of educators in schools (and people in society) working collaboratively toward transformative outcomes.

People who talk about transformational learning or educational revolution without referring explicitly to everyday life, without understanding what is subversive about learning, and love, and what is positive in the refusal of constraints, are trapped in a net of received ideas, the common-nonsense and false reality of technocrats (or worse).

Schools are alluring contradictions, harboring possibilities for liberation, emancipation, and social progress, but, as fundamentally authoritarian and hierarchical institutions, they produce myriad oppressive and inequitable by-products. The challenge, perhaps impossibility, is discovering ways in which schools can contribute to positive liberty.

That is a society where individuals have the power and resources to realize and fulfill their own potential, free from the obstacles of classism, racism, sexism and other inequalities encouraged by educational systems and the influence of the state and religious ideologies. A society where people have the agency and capacity, to make their own free choices and act independently based on reason, not authority, tradition, or dogma.

[1] These remarks were presented immediately following Seixas’ presentation and prepared without the opportunity to read the text of his talk in advance. As a result, they are based upon the abstract circulated prior to his seminar and my understanding of Seixas’ perspective based upon his published work and our interactions as faculty members at UBC.

Video of Seixas presentation, Ross response and Q&A with audience (February 26, 2016):