Hyperculture

The last two chapters of Bolter (2001) were an excellent choice to close our readings. As an aside, I would like to say how much I enjoyed the sequencing and intertextuality of the readings in this course. Most courses I have taken offered carefully chosen readings around the key ideas and topics, but none linked them so successfully and recursively as was done here. It was helpful to my own thinking and enjoyable to read Bolter on Ong, Kress cited in Dobson and Willinsky, and so on. I could cite such pairings all the way back to the first readings. It’s one of those subtle displays of good pedagogy that makes me wonder if I could do a better job selecting and sequencing the readings in my classes.

To return to Bolter, however, the argument that the technology used for writing changes our relationship to it (p. 189) seems almost self-evident. I know that my approach to writing changes when the tool is a pen versus a word processor. And it is largely for this reason that I avoid text messages. I worry how typing on a tiny keyboard with my thumbs to any great extent would affect my relationship with writing (which is already sufficiently adversarial). The discussion of ego and the nature of the mind itself as a writing space was also interesting. I’m not sure that I can follow where Bolter leads when he suggests that if the book was a good means of making known the workings of the Cartesian mind, hypertext remediates the mind (p. 197). That, it seems to me, accords too little to the ego and too much to networked communications—at least as they currently exist.

Bolter is certainly correct, however, when he asserts that electronic technologies are redefining our cultural relationships (p. 203). This is especially true for my students. Writing in 2001, Bolter preceded Facebook by at least three years, but he could have been doing Jane Goodall-style field research in my school (watching students use laptops, netbooks and handheld devices to wirelessly access Facebook) when he suggests that we are rewriting “our culture into a vast hypertext” (p. 206). My own efforts at navigating the online reading and writing spaces of the course were, I fear, somewhat hampered by having lived most of my life in “the late age of print.”

I didn’t post a lot of comments, although I attempted to chime in on the Vista discussions. What I realized late in the game was that I should have been more active in posting comments to the Weblog. The strange thing is that I enjoyed reading the weblog posts—and especially enjoyed reading the comments people made about my weblog postings. For some reason, however, that didn’t translate to reciprocating with comments in that space. Perhaps it’s because I’m not a blogger or much of a blog reader outside of my MEd classes. I still prefer more traditional (read: professional, authoritative) sources for news and opinion. Though, truth be told, I probably read as much news and opinion online as in print. It doesn’t hurt that the New York Times makes most of its content available online for free and that I have EBSCO and Proquest access at work. It might also be because the other online courses I’ve taken in the past two years tended to use the Vista/Blackboard discussion space as the discussion area, so I think of that as the “appropriate” space for that type of writing. It’s fascinating to analyze one’s own reading and writing behaviours and assumptions in light of what we’ve read and discussed. It also takes me again to my own practice as a teacher. When I next use wikis, for example, with my students, I will try to devise a way (survey, discussion tab in the wiki, etc.) to find out how they believe their previous online reading and writing experiences influence their interactions and contributions.

References

Bolter, J.D. (2001). Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

December 2, 2009 2 Comments

Rip.Mix and Feed Animoto

I opted to use Animoto.com for my rip.mix.feed contribution. It’s a Web 2.0 tool that bills itself as “the end of slideshows.” It allows the user to combine images and music (which you supply or choose from their selections) in a type of music video/mashup. The site takes care of transitions between the images using a variety of effects adjusting timing to the chosen music. The free version (which I used) is limited to 30-second compositions. All of the images I used, apart from the first one, I found in Flickr searches for images with creative commons licensing. (I have a list of all the Flickr URLs and if anyone is interested I can post it as an attachment.) The start image was generated with the Bart Simpson chalk board generator. The number of images one can squeeze into 30 seconds varies somewhat depending on the music selected, but is around 15-18. Fast-paced tunes show the slides more quickly and use a few more images than slower ones. The site allows for easy remixes, and it’s possible to add and remove images until the desired effect is achieved. It’s also possible to get stuck endlessly tweaking while looking for the ‘perfect’ edit (don’t ask me how I know…). I’ll post links to two versions that use the same images but different music. The first, which I not very creatively called Text technologies 1, uses 30 seconds of a song called Finally by the Sunday Runners. The second, Text technologies v.2, uses a faster indie piece called 1234 by Fake which I enjoy for its lyrics: “I’m just sick of my school, and my teacher’s a fool..” Certainly, many Web 2.0 tools are fun and engaging. Every time I (re-)make this realization I tell myself that I have to get more creative about encorporating them into my lessons!

December 1, 2009 2 Comments

From one literacy, to many, to one

There is no question that for students in the K-12 system in North America the ‘new’ literacies afforded by digital technologies play an integral role in their lives. The question is what role they should play in schools. Most of these students have never known a time without the Internet and have not had to do research when Google (circa 1998) and Wikipedia (2001) were not options. The question of whether these new tools for finding information and the skills required to use them1 are literacy is moot for these students. It is a question posed by those attempting to make sense of a rapid change in the learning styles and methods of their students—and in that sense it is necessary and useful. However, any consideration of new literacies as ‘lesser’ literacies entirely misses the point. The new literacies of what Bolter (2001) repeatedly terms “the late age of print” are additive in nature. That is, though there is much debate about the relative merits of various forms of representation, the effect is evolutionary and cumulative rather than revolutionary and exclusionary. Many literacies co-exist, supplement one another, extend into one another, and borrow and trade metaphors. As Dobson and Willinsky (2009) note, “…the paradox [is] that while digital literacy constitutes an entirely new medium for reading and writing, it is but a further extension of what writing first made of language” (p. 1). Certainly, for K-12 students, ‘new’ literacies are not new, they are simply literacy. Thus, multiliteracy, new literacy, digital literacy and information literacy, while useful concepts in the effort to problematize and deconstruct the changes, are all facets of one, evolving and growing literacy. Writing in 1996, the year many students currently in the eighth grade were born, the New London Group argued that “…literacy pedagogy now must account for the burgeoning variety of text forms associated with information and multimedia technologies” (p. 2). Whether accounted for or not, those forms and technologies are taken for granted by most students. It seems likely that ignoring this results in a type of cognitive dissonance for students which may make it more difficult for them to learn in classrooms in which print literacy is still the dominant, if not the only, mode. A danger, however, as Dobson and Willinsky (2009) note, is the tendency to assume that “…adolescents’ competence with new technologies—is often inappropriately reconstrued as incompetence with print-based literacies” (p. 11). Some technology enthusiasts, notable among them Marc Prensky, call for a wholesale shift from print to digital literacy.

Prensky has gone so far as to claim that “…it is very likely that our students’ brains have physically changed—and are different from ours—as a result of how they grew up” (Prensky, 2001, p. 1) and their immersion in digital technologies. While there has been some interesting research in recent years on brain plasticity, particularly with reference to interactions with technology, Prensky is justly criticized for going beyond the scientific evidence (McKenzie, 2007). Yet he does highlight important characteristics of the way students now learn and socialize2 using technology. Similarly, Prensky’s classification of parents and teachers as Digital Immigrants, and their children and students as Digital Natives, though overly simplistic is not entirely unhelpful in conceptualizing the current situation in classrooms. As with other immigrants, some adults have a more difficult time adapting to a new culture than do their children who have been raised in that culture. Of course, the situation is not as black and white as Prensky would have us believe. It is also sometimes true that adults who have made the choice to emigrate, and have done the research and made the sacrifices necessary to act on that choice, are more knowledgeable and participate to a higher degree than do their children who take the advantages and freedoms of the new country for granted. It is normal to find students today who have high

speed Internet access at home, access to a family desktop computer or a desktop, laptop or netbook computer of their own, a cellular telephone (capable of texting and taking photos and short movies), and an iPod or other MP3 player. In fact, the preceding is almost a list of standard equipment for a teenager in early 21st Century North America. And while it is still true that many schools do not encourage the use of most of these technologies in the classroom, an interesting phenomenon can be observed when teachers make an attempt to do so. The teacher, likely a Digital Immigrant in Prensky’s terms, has made some study of the technology to determine the ways in which it can be most usefully employed in pursuit of particular curricular objectives. What often becomes clear is that many of the Digital Native students, who appear quite facile with technology to the casual observer, are both a.) using only limited aspects of technology primarily for social purposes (MSN, Facebook, Twitter, etc.); and, b.) not fully comprehending the implications of the uses they do make of the technology. This is particularly evident with regard to services such as Facebook where it is not uncommon to find that students rely on default privacy settings, do not read the contract they agree to when opening an account which states that all material posted to the site becomes the property of Facebook, and do not consider the potential long-term consequences of statements or images they post. In short, students are not only taking the technologies and literacies for granted, they have little or no explicit understanding of them. What this argues for is again something that was anticipated by the New London Group thirteen years ago: the need for teachers and students to come together in a learning community to which both parties bring their knowledge, experience, learning styles and literacies.

To be relevant, learning processes need to recruit, rather than attempt to ignore and erase, the different subjectivities, interests, intentions, commitments, and purposes that students bring to learning. Curriculum now needs to mesh with different subjectivities, and with their attendant languages, discourses and registers, and use these as a resource for learning. (New London Group, 1996, p. 11)

Dobson and Willinsky (2009) hit exactly the right “Whiggish” note in the closing remarks to their draft chapter on digital literacy: “We must attend to where exactly and by what means digital literacy can be said to be furthering, or impeding, educational and democratic, as well as creative and literary, ends” (Dobson and Willinsky, 2009, p. 22). It is clear that the result of this attention must be an expansion of the definition of literacy to include many aspects made possible by its digital evolution.

Notes

up1 Dobson and Willinsky (2009) point out that literacy in the digital age includes the skills, often defined as information literacy, “… not just for decoding text, but for locating texts and establishing the relationship among them” (p. 19).

up2 “Social software constitutes a fairly substantial answer to the question of how digital literacy differs from and extends the work of print literacy” (Dobson and Willinsky, 2009, p. 21).

References

Bolter, J.D. (2001). Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Dobson, T. and Willinsky, J. (2009). Digital Literacy. From draft version of a chapter for The Cambridge Handbook on Literacy.

McKenzie, J. (2007). Digital Nativism, Digital Delusions, and Digital Deprivation. From Now On, 17(2). Available: http://fno.org/nov07/nativism.html

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. On the Horizon. NCB University Press, 9(5).

November 29, 2009 1 Comment

Electronic books: Not yet the remediation of print

The cost of digital alternatives has been a factor in their adoption. E-books read using a home computer are cost effective since few people in developed countries do not already own a PC capable of running the required software. However, the initial cost of purchasing a dedicated e-book reader, particularly for fiction, is still prohibitive. There are also lingering issues of portability, readability and battery life, though these are certain to be addressed over time. For non-fiction materials, particularly encyclopedias and reference works, however, portability works to the advantage of e-books and uptake has been faster and more enthusiastic. High school students are content to use electronic versions of reference works that are, in print form, typically larger, heavier, and available for shorter loan periods than other types of materials. And, in addition to 24/7 availability online, electronic reference books offer the advantages inherent in most digitized material: “Specifically, electronic documents are usually searchable, modifiable, and ‘enhanceable.’ ” (Anderson-Inman & Horney, 1997, p. 487). At the post-secondary level, where students purchase their books, electronic texts are popular with a majority of students for many of the same reasons (Hawkins, 2002, p. 45). “As with any remediation, however, the eBook must promise something more than the form it remediates: it must offer what can be construed as a more immediate, complete, or authentic experience for the reader” (Bolter, 2001, p. 80). Again, to date, this is most true for reference works and most notable for encyclopedias.

Fanfiction.Net (www.fanfiction.net Nov. 11, 2009) employs attributes of Web 2.0 popular with teenage readers. Fanfiction, as the name suggests, is a site that allows users to write chapters and scenes based on their favourite works (novels, plays, movies and television shows), and publish them to thousands of readers. Readers can browse these user creations by category and read them online as long as they have a computer with an Internet connection or access to one in a school or public library. The fan compositions reflect the interests and preoccupations of the time, and reach a wide audience through Internet publication facilitated by categorization, searchability and interactivity (ratings and reviews). Forums and communities allow readers and writers to discuss their works, the shows and books on which they are based and a wide range of related topics. English, literature and creative writing teachers would do well to co-opt the enthusiasm for this type of interaction with popular culture to encourage students to write for a much wider audience than that available in the classroom or the school. Interestingly, while Fanfiction incorporates many Web 2.0 affordances, it is also still linked strongly to the metaphor of the codex. Hawkins (2002) sums up the current situation well: “E-books will survive, but not in the consumer market—at least not until reading devices become much cheaper and much better in quality …. The e-book revolution has therefore become more of an evolution.” (p.48).

References

Anderson-Inman, L. & Horney, M. (1997). Electronic books for secondary students. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 40 (6), 486-491.

Bolter, J.D. (2001). Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hawkins, D. T. (2002). Electronic Books: Reports of their death have been exaggerated. Online, 26(4), 42.

November 17, 2009 2 Comments

Yellow journalism

My brief look at how yellow journalism evolved during the penny press era in response to social, market/economic and technological developments in the late 19th Century is posted here at the wiki site.

November 7, 2009 1 Comment

Time to set aside childish uses of technology

From Ong and his critics to O’Donnell, Brand, Kelley and Grafton grappling with some of the more pressing concerns of the digital era (storage, digitization of books and access to same, respectively)—Module 2 covered a lot of ground! I particularly enjoyed Kelley’s discussion of the economic aspects of digitization (shipping books to China for scanning, for example), and contrasting of business models (a much under-rated influence) as the world of copyright and protected copies gives way—not without much wailing and gnashing of teeth—to the age of free (though not worthless—an important distinction) digital copies. Kelley is correct: “The reign of the copy is no match for the bias of technology” (2006, p. 13).

The question of how this progression of technologies has and will continue to modify reading and writing and thus education is not just at the centre of this module, but of the course. I couldn’t help, however, relating this discussion to one in which I have been engaged for some time now concerning the role of information and communication technologies (computers, cell phones, smart phones, social networking applications, etc.) in the lives and learning of our students. As a secondary teacher, I tend to think of that age group first in this regard, particularly since I believe it’s still the age (13-18) of most rapid adoption and most intense use. Having said that, I am regularly told of middle schoolers developing cell phone and Facebook habits to rival those of their older contemporaries, and undergrads still inhabiting the high school world of more than a thousand text messages a day and religious, narcissistic Facebook updating.

This particular facet of technology in schools: the uses it is put to by teens and the effect it has on their learning, was the focus of our school pro-d Sept. 25—which I inadvertently became involved in organizing. I’m not on the pro-d committee, but as the teacher-librarian responsible for purchasing, I was asked to order 80 copies of the book The Dumbest Generation: How the Digital Age Stupefies Young Americans and Jeopardizes Our Future —one for each member of the teaching staff. They arrived on the last day of school in June and were distributed for summer reading. Then last month I was again recruited to set up a Skype discussion with the author, Mark Bauerlein, an Emory University professor. Bauerlein acknowledges that the title is a provocation and adds that he is not a technophobe. One of his main arguments is that while there is clearly tremendous power in the current technologies of reading and writing that we employ (email, databases, online access to thousands of books and newspapers, blogs, wikis, etc.), and we would certainly not want to give them up, the uses to which teens put them as a result of their developmental stage locks them into a kind of adolescent feedback loop. This narrow preoccupation unnaturally extends adolescence (mentally, at least) to the detriment of acquiring knowledge and maturity—which are, after all, also important functions of secondary and post-secondary education. Bauerlein opened our 67-minute pro-d Skype session with a 15-minute summary of his thesis, and then fielded questions from teachers. He was challenged as often as he was lauded, but I must admit, I find his argument persuasive an in accordance with my observations and those of many of my colleagues. I have been teaching secondary full-time for a decade now, so I experienced roughly five years of little to no cell phone and Facebook penetration before the explosion in their use of the last five years. Again, I think Bauerlein is correct to worry about the quality of communication texting and the Facebook Bathroom Wall promote as well as the 24/7 intrusion of adolescent concerns (What are my friends doing? Where are we meeting tomorrow? Who said what about whom?) that these technologies permit. The mental space and even quiescence that used to exist when teens were alone at home in their rooms reading or doing homework no longer exists thanks to texting and Facebook. Bauerlein suggests that the current technologies allow teens to become far too self-referential and this crowds out the (previously) natural expansion of interests to less egocentric concerns. Of course, there is still the top 10 percent who will use ICTs to organize peace rallies and email pictures of a toxic spill to the traditional media (after starting a Facebook and Twitter group on the topic). It’s the other 90 percent he worries about—and I agree. In any case, coming out of this pro-d dialogue, I may have come off a little more curmudgeonly than usual over in the Orality and Literacy discussion where I chimed in with some of these musings in a thread started by Drew. I’ll see if I can attach an excerpt of the Skype discussion with Bauerlein. (He gave me permission to record the exchange.)

Note: Bauerlein does allow that most of the studies in his book are American and his observations are about U.S. teens. I would submit, however, that based on similar Canadian studies I have seen, the behaviour of Canadian teens is not significantly different where ICT use is concerned.

References

Bauerlein, M. (2008). The Dumbest Generation: How the Digital Age Stupefies Young Americans and Jeopardizes Our Future. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher.

Kelley, K. (16 May 2006). Scan This Book! New York Times.

October 5, 2009 2 Comments

What’s Wrong with Ong?

Determinism and Great Divide theory

In Orality and Literacy, Ong sets out some useful comparisons, but falls into the trap of implying that the categories he uses to describe and enumerate the differences between oral and literate cultures are sufficient to describe them. Further, in an attempt to support the Great Divide theory he elaborates, he ventures into technological determinism with the claim that technology shapes man—particularly, the way people think.

Ong (1982) writes: “Technologies are not mere exterior aids, but also interior transformations of consciousness, and never more than when they affect the word” (p. 81). This introduces a kind of chicken and egg argument since man has first to find a reason and the means to invent a technology in order for it to have its purported transformational effect on consciousness. In Ong’s view, writing is the technology that not only distinguishes oral from literate cultures, but also creates a schism between because it changes the very way they think: “More than any other single invention, writing has transformed human consciousness” (Ong, 1992, p. 77).

A more recent advocate of a similar view concerning the effects of technology on the minds of students is technophile Marc Prensky. He has famously argued that current students, whom he terms Digital Natives, have been mentally transformed by the various technologies to which they have been exposed to the point that the methods used by their Digital Immigrant teachers are no longer effective: “…it is very likely that our students’ brains have physically changed—and are different from ours—as a result of how they grew up” (Prensky, 2001). Prensky has been justly critiqued by numerous writers, including McKenzie (2007), who dismisses Prensky’s brand of determinism in Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants as “…a rather shallow piece lacking in evidence or data, Prensky offers the terms ‘digital natives’ and ‘digital immigrants’ to set up a generational divide. His proposition is simple-minded. He paints digital experience as wonderful and old ways as worthless.”

It should be noted, however, that notwithstanding his journey down the slippery path of technological determinism, Ong has done useful work in elaborating the distinctions between oral and literate cultures. If, in fact, his categorizations were a rhetorical device of the sort he discusses (Ong, 1982, p. 108), an agonistic means of illuminating the differences between literate and oral cultures, it would be more effective. Instead, as Chandler (1994) points out, such binaries lead to a “… sharp division of historical continuity into periods ‘before’ and ‘after’ a technological innovation such as writing assumes the determinist notion of the primacy of ‘revolutions’ in communication technology. And differences tend to be exaggerated.” There is also the danger of generalizing too widely and overlooking potential overlap.

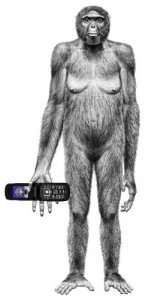

Technological determinism? It didn't take long for someone to imagine what impact 21st century technology might have had on Ardi.

It is an interesting coincidence that in the same week the class is studying Ong’s Great Divide approach to orality and literacy, another classic Great Divide is being seriously challenged. News of ‘Ardi’ (short for Ardipithecus ramidus) a specimen of a female human precursor who predates the famous 3.2 million-year-old Lucy by a million years, appears to throw into question the missing link theory of human evolution (Shreeve, 2009). Paleontologists have long studied chimpanzees, assuming a human evolutionary path from apes to Lucy. Ardi now makes it appear that any common ancestor might have been much further in the past and unlike modern apes. Here again, the understandable, logical tendency to categorize, compare and contrast—strategies we teach students in English class to prepare their compositions—sets up overly simplistic false dichotomies which do not, ultimately, provide a complete picture.

As Chandler (1994) observes, dichotomy is sometimes an attempt to simplify complexity—in the case of orality and literacy, cultural complexity. Such complication is far more likely to result not in a clean break between orality and literacy, but in an overlapping of the various systems based on more mundane and practical considerations such as trade and commerce. This, in turn, challenges the elitism in the deterministic view such that, as Gaur (1992, p. 14) argues, there are no primitive scripts “…only societies at a particular level of economic and social development using certain forms of information storage” appropriate to their circumstances. Thus, continuity theories (Chandler, 1994), offer a more complete view incorporating the notion of interaction between overlapping modes and media which, in turn, allows for a more evolutionary and less deterministic understanding which eliminates the need for a missing link to explain historical discontinuities.

References

Chandler, D. (1994). Biases of the Ear and Eye: “Great Divide” Theories, Phonocentrism, Graphocentrism & Logocentrism [Online]. Available: http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/litoral/litoral.html

Gaur, A. (1992). A history of writing [revised edition]. London: British Library.

McKenzie, J. (2007). Digital Nativism, Digital Delusions, and Digital Deprivation [Online]. From Now On, 17(2). Available: http://fno.org/nov07/nativism.html.

Ong, W.J. (1982). Orality and Literacy. New York: Routlege.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. On the Horizon. NCB University Press, 9(5) [Online]. Available: http://pre2005.flexiblelearning.net.au/projects/resources/Digital_Natives_Digital_Immigrants.pdf.

Shreeve, J. (1 October 2009). Oldest “Human” Skeleton Found—Disproves “Missing Link.” National Geographic Magazine [Online]. Available: http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2009/10/091001-oldest-human-skeleton-ardi-missing-link-chimps-ardipithecus-ramidus.html

October 4, 2009 2 Comments

Mixing molten lead and Blackberries

When I think of the technology of text, something like the image above (a small Goss newspaper press) usually comes to mind. The first time I saw one, I was impressed by the size and mechanical complexity of it. Later, when I met some of the older pressmen, they told me stories of the hot lead days–a few even had scars on their forearms from when the slugs (letter forms) would jam as they were sliding into place and, if the pressmen weren’t quick enough, hot lead would spray on to their arms.

Last week, I walked behind a student in the hall madly jabbing her thumbs at a tiny cell phone. The presses always made me think of the New York Times, democracy, mass distribution, and public debate. The cell phone makes me think: “c u l8tr” and a rendezvous at the mall. How does the medium shape the message?

September 20, 2009 No Comments

Ozy

One of my first memories of text as something interesting and powerful came from what I at first thought was a ‘dumb’ exercise in public speaking. My Grade 9 English teacher, an Englishman with a blue nose that we suspected was the result of a fondness for pints, required that we memorize and recite a short poem. He offered to help us choose something suitable, and in my case, suggested Shelley’s Ozymandias. As I read it over and over to memorize it, a funny thing happened: I started to like it, I started to appreciate its irony and world weariness. I recited it flawlessly, and can still remember it to this day (though, I admit, I looked it up online to check my memory before posting it below).

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: “Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown

And wrinkled lip and sneer of cold command

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed.

And on the pedestal these words appear:

`My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings:

Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare,

The lone and level sands stretch far away”.

–Percy Bysshe Shelley

September 20, 2009 2 Comments

The future of reading?

ebooks kindle amazon, originally uploaded by libraryman.

I chose this image because it features the Kindle (a digital book reader) which combines two of the key preoccupations of the course: text and technology. Discussions about the Kindle were briefly the rage among technophiles at my school, until it became apparent that, at least initially, the device would only be available in the U.S.

I’m Phil, a teacher-librarian and journalism teacher at Centennial School in Coquitlam, B.C. I’m in my 10th year as full-time secondary teacher, after seven years in the Canadian newspaper business. My last newspaper job was working as a copy editor at the Toronto Star. I was born in Vancouver and raised in the Okanagan, so it didn’t take long before the desire to come home set in. I had moved to Ottawa to do a master’s in journalism at Carleton, and it was there, working as a TA in Journalism 100, that I started thinking about teaching as a career. A bleak Toronto winter sealed the deal. After earning my BEd at UBC, I started teaching English and journalism. At Centennial, the teacher-librarian asked if I would be interested in taking a library block to help with Internet and digital (then CD-based) resources, and in the years that followed I slowly picked up library blocks and dropped the English classes. I wasn’t too interested in pursuing an MEd in teacher-librarianship until recently when it became apparent that the role of technology was being more closely examined by TLs. I’m an early adopter, but also a skeptic. Technology is costly for schools and many of its affordances and non-monetary costs are poorly understood. As Postman pointed out in the Technopoly excerpt (which I confess I read from my print copy rather than the PDF), there are costs as well as benefits in all technologies. It seems the school community is populated with technophiles and technophobes, and an insufficient number of people willing to inhabit the murkier middle ground. This will by the final course in my program and I am looking forward to it. However, I was waitlisted and just given access last week, so my first task is to catch up with the rest of the class!

September 20, 2009 No Comments