Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the fourth leading cause of death in Canada and is currently affecting nearly 2 million Canadians 35 years of age or older. This incurable, progressive disease is described to feel as if you are slowly drowning making it clear how much damage it can cause.

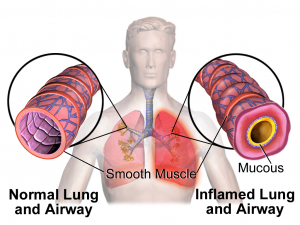

Picture the lungs as networks of different branches from one trunk. As these branches move further out, they will branch off more and become smaller and smaller. As you can imagine, damage to these branches can have catastrophic effects where patients slowly lose their ability to breath. This is what happens to people with COPD. These branches become damaged causing inflammation and narrowing of branches called bronchi. This damage can make it so hard to breath that even a quick trip to the fridge seems impossible. Due to its progressive nature, researchers are looking into treatments that can reduce the progression of COPD.

Changes to airways as COPD progresses (Source: Wikipedia Commons)

Early detection is a key component to controlling COPD progression. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) has been established for standardizing COPD progression. GOLD creates a 4 staged index from mild to very severe COPD based on a breathing test that assesses lung capacity. This helps doctors to understand how damaged the lung tissue.

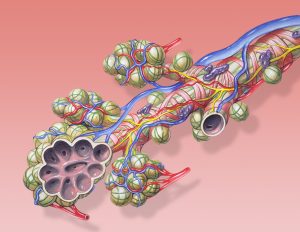

Although this has been an excellent tool for diagnosing COPD, researchers have noted that some of the very fine, small branches, where gas exchange occurs, are not well understood. Understanding this gap of knowledge between lung function and onset COPD is critical for developing effective treatment plans.

A recent study published by investigators from the Centre for Heart Lung Innovation was some of the first to try to fill this hole. The results were astounding, showing that nearly 41% of the terminal bronchioles are lost in mild and moderate cases of COPD. This would mean that patients who present very little symptoms are already losing a significant portion of their terminal branches. When finally diagnosed, the disease may be more advanced than previously thought. Even more importantly, mild and moderate COPD patients receive minimal treatment according to current guidelines- these results may change that protocol.

Terminal Bronchi with alveolar sacs for gas exchange. (Source: wikipedia creative commons)

The knowledge gained from this study may help to explain why many clinical research trials for COPD have fallen short. If disease progression is more severe than originally believed, the cohorts being used may not be appropriate for the study. This result may change how many studies are structured in the future.

The researchers have emphasized that these results are preliminary, and more research should be done with larger cohorts before any large conclusions can be drawn. However, this does start the conversation on current treatment plans and where changes may need to occur to better diagnose COPD in its early stages. This in turn will hopefully lead to better outcome in treatment of its progression.

By: Katie Donohoe