Introduction

The use and distribution of free textbooks in Mexico’s grade schools stimulated the development of literacy within the country and the outreach of information to the poorest and most isolated areas in the nation. The distribution of these textbooks helped promote national values as well as the democratization of information distribution.

In this paper, we will briefly review the historical context in which Mexico’s free textbooks were introduced to this country’s educational system as well as analyze some of the implications textbooks had in the development of education and literacy within this country.

Context and development of free textbooks in Mexico

To be able to fully understand the implications of the introduction and use of free textbooks in Mexico’s educational system, we must first understand how this system was established and what were the first steps towards the development of nation-wide textbooks.

Mexico’s educational system as we know it today was formally established in September 1921 with José Vasconcelos as the first Secretary of Public Education. Initially, the Secretary’s tasks were to organize courses, open schools in the various states and municipalities, edit books and create public libraries. All of these actions supported the successful initiation of a nationwide educational system.

Vasconcelos’ main goals were to strengthen the system and provide education within the various developing professions and occupations in Mexico, such as: railroads, the textile industry, construction professionals, teachers, graphic arts professionals and typewriter technicians. Although Vasconcelos’ efforts were evident in the years he headed the department, the presidential electoral rebellion in 1924 endangered the newly founded department and the entire educational project.

A couple of decades after the rebellion (1944), Jaime Torres Bodet, an apprentice of Vasconcelos and newly appointed Secretary of Education in Mexico, was worried about the high cost of textbooks used in elementary education in Mexico. Although free public education was guaranteed constitutionally, textbooks were very costly and of low quality, making them inaccessible to poor families and people in rural areas in the developing country, since initially they had to be purchased by the students at a relatively high cost.

When Adolfo Lopez Mateos became president in 1958, he was faced with a poor country with high levels of illiteracy and inequity regarding access to education and information. He stated that a school could do very little for the children, if the parent didn’t have enough economic resources to buy the basic textbooks (SEP, 2009). It was at this time that the Secretary of Education Torres Bodet pushed for a nationwide literacy campaign with the idea that every student within grade school age should assist school with a textbook paid for and provided by the federal government. This is how the National Commission for Free Textbooks (Comision Nacional de Libros de Texto Gratuitos- CONALITEG for its initials in Spanish) was born and officially established in February, 1959. The idea of this commission was that the free textbook would be a social right, as well as a vehicle that facilitated dialogue and equity in school.

Since the intention of the textbooks was to democratize information, facilitate knowledge and reach the entire country, the initial task of developing the books and deciding on their content was crucial. This titanic and critical process was designated to Martín Luis Guzmán: a member of the military, journalist and Nobel Prize winner in Literature whose efforts resulted in the creation and consolidation of CONALITEG’s mission and the production of books which supplied the nation’s educational and information demands. Several books on different topics and for different grade levels were produced and revised for students as well as for teachers.

By 1972, CONALITEG produced 43 books for students and 24 for teachers (SEP, 2009), these books integrated the educational reforms presented by President Luis Echeverría and were constantly modified to integrate subsequent reforms and new educational content. In 1982, the CONALITEG elaborated books with specific information for each of the states which, in the early nineties were transformed into regional books with historical and geographical information for each of the 32 states.

In 1992, Mexico’s Public Educational System launched an integral reform named the Educational Modernization Program, which gave the free textbook an upgrade in content, presentation and delivery. The goal of this new program in relation to the textbooks was to reach most elementary schools before the school year began.

Discussion

Socially, historically and education-wise, free national textbooks in Mexico were introduced at the right moment in time and with the necessary support from the federal government. Mexico’s citizens, especially those in rural areas or with low incomes immediately adopted the textbooks, as they considered them a potential solution to the growing problem of illiteracy, resulting in a reduced number of people with the necessary training in the various growing professions and occupations. Having being granted free textbooks, rural families found it much easier to take their children to school to continue their educational development. The educational system, on the other hand, found an opportunity to reinforce nationalism and distribute the same information (historical, scientific, etc.) to the entire grade school population.

One of the historical events that helped drive the founding of CONALITEG and the elaboration and distribution of textbooks in Mexico, was the institution of the Department of Public Education as it was the ultimate effort to federalize and consolidate educational efforts nationwide. Along with the creation of this Department and the founding of CONALITEG, came the centralization of information to facilitate its distribution and access. Although it might be paradoxical, centralizing these efforts, allowed democratization of education and information in the country.

With democratization of information the education system in Mexico faced, as it currently does, an extremely difficult challenge which is to integrate and contextualize the information appropriately for these textbooks. The main questions with this issue are: What should (and should not) be included and how should “the story” be told? For many Mexicans, the textbooks provided by the Public Educational System, are the only medium of information they’ll ever have access to (Corona, 1997). According to Corona’s research on the integration of history textbooks in Mexico: “Mexico/EUA: “guerra de razas” en los libros de texto” (1997), the educational system has modified the textbooks according to the historical, social, economical and contextual needs; pointing out or focusing on different historical events depending on the era and social needs. A clear example is the way Mexico’s textbooks portray its relationship with the United States differently within each historical era: “The USA becomes the “good neighbor”” (Corona, 1997, pg. 12) vs “The relationship between Mexico and the USA are closer to barbaric and war-like of military dominance” (Corona, 1997, pg. 11).[1] Other examples of this “issue” are the science and sexual education or health books which have modified its content to adapt the new information and scientific theories now known and approved. The integration of new knowledge in the textbooks is a polemic issue because of the levels of illiteracy and inaccessibility to knowledge and educational opportunities in Mexico. An important issue to mention in this report is the fact that the Mexican government provides “official” versions (not necessarily historically correct) of the country’s history which mold students’ ideas and value systems. A clear example of this was the way history textbooks portrayed one of the political parties (PRI) that maintained power for over sixty years in the country, always mentioning the positive aspects of the party and of the government in turn.

We now reflect on the great responsibility the federal government has with its population: to provide the means and information necessary to help them learn on their own. A “risky”, but necessary action is to teach Mexico’s population to think and question the government, its policies, etc.

Conclusion

Textbooks and the federal education system as a whole have faced many challenges throughout the years. First, the challenge was to cover the entire country with schools in every state and municipality; next was creating the adequate resources, and finally to update and renew these materials to adapt them to the historical and changing social needs of the country.

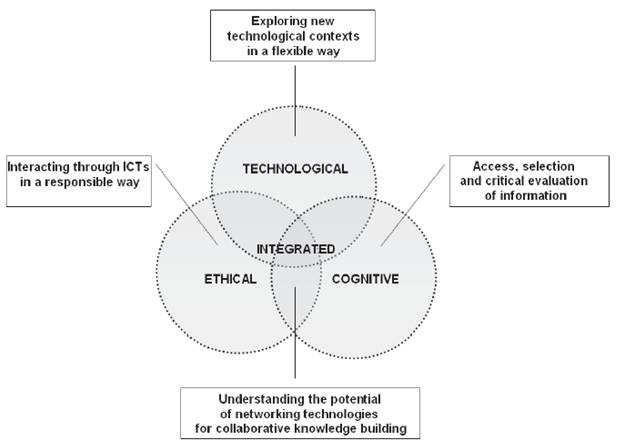

Currently, the challenge is to elaborate digital versions of the textbooks to be able to revise and renew its information constantly and at a low cost. Information is changing ever so rapidly such that Mexico cannot afford (economically and socially) the high costs of producing the textbooks with old or obsolete information. Another challenge that the educational system has to consider is the integration of new resources of information to the elaboration of textbooks- collaborative writing and production of knowledge.

The nation-wide free textbooks that Mexico’s educational system provides to its elementary level students has been an alternative to assure that everyone has access to at least the same “official” information, although the challenge to renew and question history, as well as other relevant subjects remains pending.

References:

Corona Berkin, Sarah. (1997). MÉXICO/EUA: una “guerra de razas” en los libros de texto para niños mexicanos. Estudios Sobre las Culturas Contemporáneas, 3(6), 49-69. PDF File Retrieved on October 19, 2009 from EBSCO database, also available in: http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?vid=1&hid=111&sid=28484310-cada-4075-a0e2-165374be5b59%40sessionmgr104&bdata=JmFtcDtsYW5nPWVzJnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=zbh&AN=15074531

León, Felipe. (Abril, 2006) La liberación de los libros de texto gratuitos en México. Aprender la Libertad. Retrieved on October 20, 2009, from: http://www.aprenderlalibertad.org/2006/04/16/la-liberacion-de-los-libros-de-texto-gratuito-en-mexico/

Secretaría de Educación Pública, SEP (2009) Historia De La CONALITEG (1944-1982). Retrieved on October 19, 2009, from: http://www.conaliteg.gob.mx/index.php/historia

Secretaría de Educación Pública, SEP (2009) Historia de la SEP. Retrieved on October 20, 2009, from: http://www.sep.gob.mx/wb/sep1/sep1_Historia_de_la_SEP. The webpage was last updated on October 5, 2009.

[1] All translations in references have been made by Ana Cecilia Tagliapietra